Speech to the World Taxpayers Association & Taxpayers Australia Conference, 2004

The interface between taxation and work has rightly become a central focus of policy debate.

Like most countries, Australia faces an ageing population with a declining ratio of working people to retired people. Amongst other things, the challenge is to ensure that the maximum number of people who can work do so, even if only part-time.

The average Australian baby-boomer, one of the most pampered age cohorts in human history, is fast approaching retirement age. On average,the boomers do not have enough savings to see them enjoy retirement at the standard to which they have become accustomed. Despite the lack of savings, most of them, I suggest, have the expectation that they can retire in luxury at 55 years of age. The public policy challenge will be not just to keep them in the workforce, but to limit the welfare transfers to them -- something that governments have had little success in doing so far.

There is a growing recognition, at least among the general public, that Australia faces a crisis of welfare dependence -- that is, there is a solid, growing minority of people locked generationally into dependency on welfare and out of work. This results in a higher incidence of crime, poor health and social dysfunction. It also acts as a sea anchor on policy change.

There is also a growing realisation that Australia's future lies with developing an innovative, entrepreneurial society based on risk-taking, investment in human capital and small enterprises.

The issue of taxation and work lies at the heart of all these problems. First, taxation in Australia -- as well in all other developed countries -- is so high and pervasive that it acts as a major impediment to any change. Second, through the proceeds of taxation, governments have become active ‘partners" in a myriad of decisions about work, retirement, welfare and risk-taking. Third, the interaction of the tax system and the industrial relations system has inhibited the expansion of commercial activity, in particular in the fast-growing area of independent contracting.

There are three areas of the policy debate on the work–tax issue that I would like to discuss, with a different perspective than that prevailing amongst the policy elite.

First, I would like to discuss the policy response to high effective marginal tax rates (EMTRs) or poverty traps. My argument will be that although there is a real problem with high EMTRs, they are a necessary outcome of our tax structure, largely caused by overly generous welfare payments. The solution lies not with more welfare -- tax driven or otherwise -- but with less. Indeed, the main reform needs to be to apply limits to welfare and to cut taxes -- the opposite prognosis to that of the policy elite.

Second, I would like to discuss the disconcerting growth in labour taxes and the conversion by stealth of labour-based charges into de facto payroll taxes.

Finally, I would like to challenge the myth that independent contractors get special tax advantages that need to be reined in.

EMTRs

As David Stevens indicated earlier, more than any country (apart from New Zealand), Australia relies on income taxation for its tax revenue. This is the case even after the introduction of the GST.

As a result, it has very high rates of income tax kicking-in at relatively low levels of income. It also does not allow as many deductions as other countries (such as income-splitting, private schools fees, interest on home mortgages). Australia also imposes some of the highest rates of tax on superannuation in the developed world.

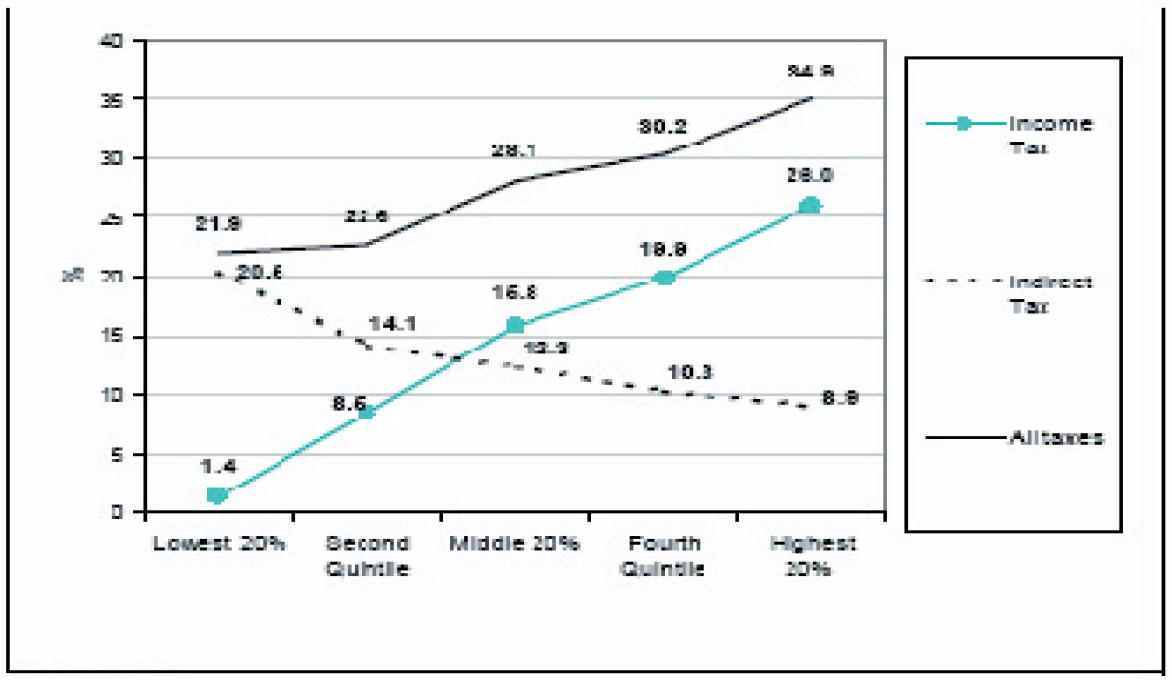

The result is a very steep income tax yield curve as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Estimated taxes paid as a percentage of gross income,

by quintile group, 2001-02 Source: Table 1

Source: Table 1

The steepness is driven by personal income tax, which increases from an average effective rate of just 1.4 per cent for the lowest 20 per cent of households to 26 per cent for the top quintile.

Although less progressive than income tax receipts, indirect taxes do decline as a proportion of income.

The aggregate tax yield curve (indirect plus income tax) measured against income goes from 21.9 per cent on the lowest quintile households to 35 per cent for the highest quintile. These estimates understate the tax burden as they do not include company taxes, taxes on superannuation or State taxes.

On the other side of the ledger, Australia has a very generous, comprehensive and tightly targeted system of welfare transfers.

On low levels of income, particularly if one is older, or has dependent children, or is a single parent, Australia welfare transfers are high, even by European standards.

Unlike Europe, however, Australia's welfare transfers are subject to tight income and assets tests. As a result, they decline sharply as gross income increases. (Gross income is measured as total income from private and public source and before taxes and government in-kind benefits.)

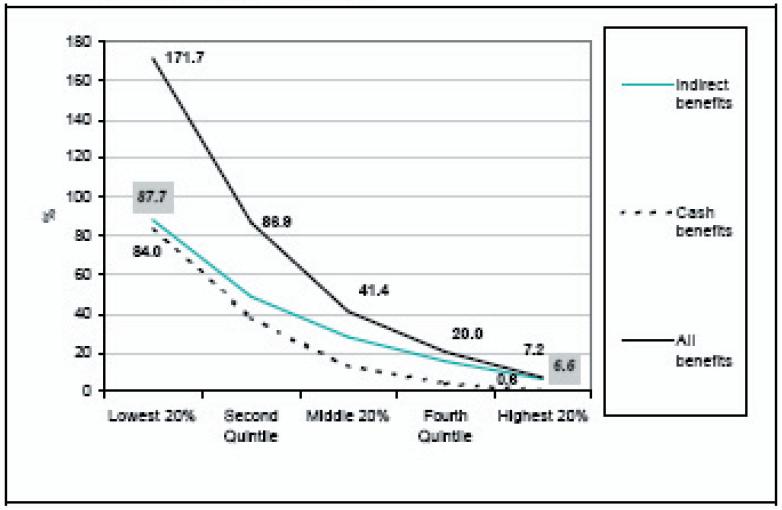

As illustrated in Figure 4, cash benefits in 2001–02 averaged 85 per cent of gross income for households in the lowest income quintile; declined to 40 per cent in the second lowest income quintile, then to around 15 per cent in the third income quintile, and then down to less than 1 per cent for the top quintile. As such, cash benefits are largely phased out by the time private income rises above average weekly full-time earnings.

Figure 4: Estimated benefits received as a percentage of gross income,

by quintile group, 2001-02

Importantly, Figure 4 show that indirect payments are actually larger than cash payments for all income quintiles. And while these payments are not as explicitly targeted as cash payments, they also decline sharply as a share of gross income across quintile groups.

The result is a very steep (or progressive) welfare transfers curve (note that the welfare transfers curve is steeper than the income tax curve), with total transfers declining from 172 per cent of gross income for the lowest quintile to less than 7 per cent for the highest quintile.

The combination of highly progressive income taxes and a generous and very progressive transfer system necessarily generates distortions in the form of high effective marginal tax rates -- as well as high average tax rates.

The high EMTRs are real, well-recognised and have been a major focus of the policy debate and tax changes for the better part of a decade.

Indeed they were a major, if not the central, focus of A New Tax System (ANTS).

ANTS, of course, introduced a GST in part to fund reductions in tax rates at median levels of income. Unfortunately, Labor and the Australian Democrats blocked the proposed reductions to the higher tax rates.

ANTS also did some house cleaning to the welfare system, including combining and stacking payments and reducing the withdrawal rate from 50 per cent to 30 per cent. All of these were designed to reduce EMTRs.

Despite these changes, EMTRs remain a problem. According to the National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling (NATSIM), even after ANTS, at least 6 per cent of the potential labour force -- almost 700,000 people -- face EMTRs of 60 per cent or more, and many retain less than 20 per cent from each dollar of private income earned.

Moreover, the EMTRs tend to fall most heavily on lower income households and household who have members considering re-entering the workforce from home duties or retirement.

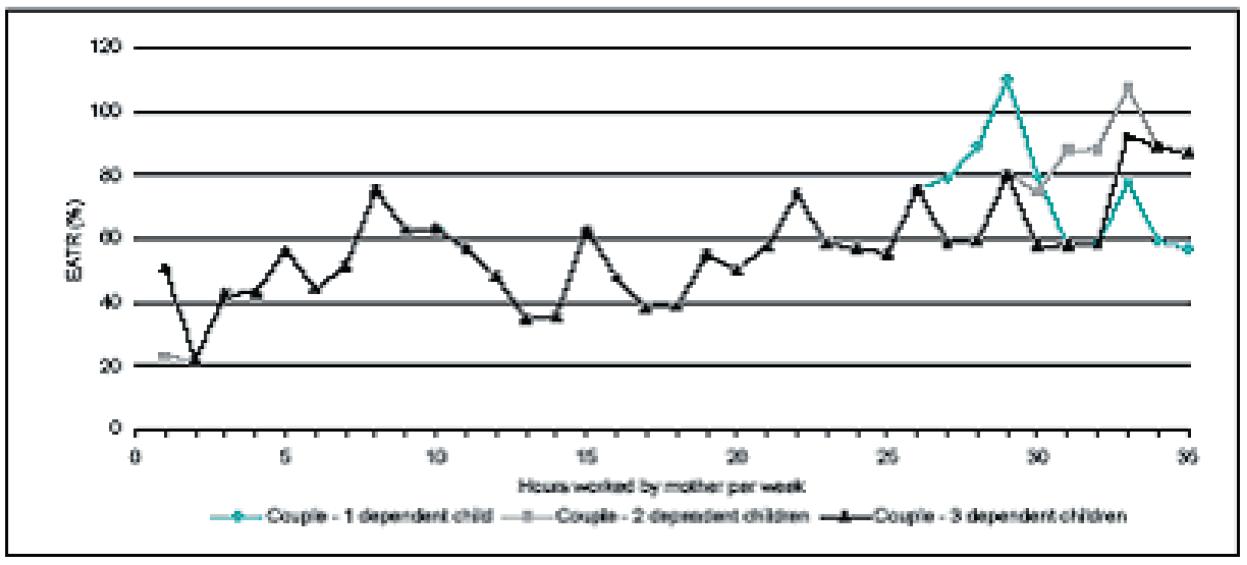

For example (again taken from research published by NATSIM), a family with a father earning a very modest income of $515 per week and the mother earning a modest income of $11.70 per hour and paying child care at $4.30 per hour will face EATRS (that is, a moving average effective marginal tax rate per hour of additional work for the woman) shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: EATRs for a family with the father earning $515 per week and the

mother earning $11.70 per hour with one, two or three children -- one

child in child care at $4.30 per hour Data source: NATSEM calculations

Data source: NATSEM calculations

As we can see, tax rates are low at very low incomes but quickly ramp up to 60 per cent, approach or even exceed 100 per cent at around a half-time work rate, and then level off at a high 50–60 per cent. Two other things to note are that the EATRs are highly volatile and that they are much higher for families with children.

The pattern is similar for single parents.

What to do?

The dominant policy approach has been conducted along two related routes. First, engage in more administrative reform focused on trying to iron-out overlaps in welfare programmes and to reduce withdrawal rates. Second, introduce earned income credits (EICs) to provide compensation for high EMTRs and provide work incentives.

I do not think either of these approach is suitable -- although cast in a different form, EICs should still be considered as a possible policy tool.

The key problem with the received policy approach is that it fails even to recognise the key problem, indeed it only makes it worse.

The main cause of the high EMTRs at low incomes -- the key target groups of the policy makers -- is the withdrawal of welfare payments. The simple empirical facts are that (1) people who are out of work in the bottom quintiles receive very high levels of welfare and, with the exception of families with more than two children, these payments are largely phased out by the time private incomes reach median levels; and (2) below median level income tax rates in Australia, while high by international standards, are not the main cause of the EMTRs.

Using the language of Bill Clinton, the catch-cry should be "it's welfare, stupid".

As for the administrative routes to reform -- these may be able to make a difference, but only marginally. EMTRs are a necessary side-effect of our tightly progressive tax–welfare system. The ANTS made a concerted effort to tackle poverty traps and reduced the share of people confronting EMTRs of greater than 60 per cent by 1 percentage point. Moreover, while it reduced the problem for some, it exacerbated it for others.

Furthermore, all the received administrative reform proposals increase welfare transfers. That is, they propose slowing the withdrawal rate of welfare payments, thereby increasing the volume of welfare payments and ultimately, therefore, increasing tax receipts and rates. The slowing of withdrawal rates has built-in limits. As the withdrawal rate is lowered by moving further up the income level, tax rate begin to increase and offset the effect of lower withdrawal rates.

In short, the administrative route is not likely to reduce EMTRs and will impose additional costs.

This is implicitly recognised by Professor Alan Duncan in the 2002 Ian Downing Lecture where he stated that "In many respects, Australia's welfare system is an excellent example of a modern and coherent welfare state, motivated by clarity of objectives and a simplicity of structure." (1) In other words, the Australian system is the model of a modern welfare system, in the eye of the policrats.

Duncan did indicate one potential area of reform:earned income credits (EICs).

EICs use the tax system to deliver welfare payments in a manner that provides incentives to work. The basic structure is to provide people a payment of, say, $4000 through the tax system upon entering the workforce and withdraw it at a set rate as earned taxable income increases.

The idea is that the EIC will compensate for the EMTRs, help cover other job-entry costs (such as travel), and provide an incentive to work.

EICs were first introduced in the US during the 1970s and they were expanded in number and values during the 1990s under the Clinton/Gingrich welfare reforms. Evidence shows that, in the US, EICs have played a crucial role in encouraging people into work, allowing them to stay in work and reducing welfare roles.

Tony Blair adopted the EIC as part of his New Labour agenda and grafted a version of the EIC on to the UK welfare system. Many Australian policrats have locked on to Blair's lead and are promoting an EIC here -- including the so-called "five economists".

The problem is that what works in the US (albeit not perfectly) will not necessarily work in Australia. Indeed, while Australian policrats are keen to adopt the EIC from the US, they are not keen on the other US policies that are crucial to the effectiveness of an EIC system.

Let me explain.

First, Australia has a far more extensive and generous welfare system and more progressive income tax system than the US, thus we have a greater problem with high EMTRs.

Second, and crucially, the US places time/volume limits on welfare eligibility which force people off welfare irrespective of the tax/welfare incentives they face. Australia does not have such limits.

Third, the Australian proposal, following the UK schemes, envisage the EIC as a new form of additional welfare and not, like in the US, as a replacement for cash payments.

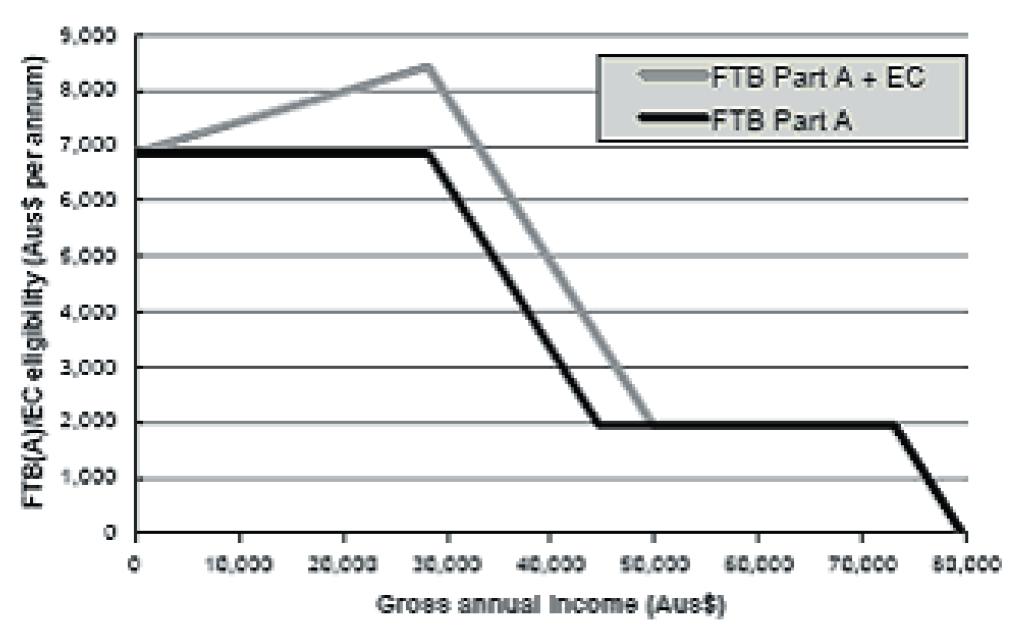

As shown in Figure 7, Lambert (2000) has proposed an EIC which builds upon and adds to the existing Family Tax Benefit Part A. Peter Dawkins (2002) has proposed another similar EIC which is a variation of the latest scheme in the UK which targets child care. Again, this scheme is envisaged as an additional payment.

Figure 7: Family Tax Benefit Part A and an Earnings Credit

There are two problems with just another add-on.

First, as illustrated in the Figure below, EICs, particularly of the add-on variety, introduce their own phase-out schedules and are a new source of poverty traps. In the Australian context of high tax rates on median incomes, an add-on EIC could easily increase the severity of EMTRs, both in terms of the number of people affected and the size of the rates.

General Impact of Reducing Rates of Withdrawal of Income Support Payments

Second, new add-on EICs must be funded, in the end, from higher taxes on others.

The problem with the Australian tax–welfare system is really straightforward -- it is far too progressive.

Welfare payments are too high for lower income and act as a disincentive to work. Tax rates on median income families are too high, acting as barriers to work, saving and risk-taking.

The reason for this is that the system has been devised with the overwhelming objective of redistributing income.

Nothing illustrates this better than the work done by the Melbourne Institute on guaranteed minimum income tax scheme.

The Institute devised a system in which the whole of the welfare system was transferred to the tax system in the form of a universal system of tax credits with a single flat rate of tax. The central aim of the exercise was to reduce the high EMTRs, while preserving the progressivity ot the welfare–tax system.

The system was calibrated so that all persons receiving a full Department of Family and Community Services (DFCS) pension or allowance were no worse off, and that there was no additional cost to the budget.

The research showed that doing this would require a flat rate of tax of a whopping 57 per cent! In other words, the volume of transfers is so large that the average tax rate is itself prohibited -- something most taxpayers already know.

Indeed this has been obvious from all the available research, but it has generally overlooked by the technocrats.

NATSIM has examined the EATRs of median and high income families and found that while they do not often face the plus-80 per cent tax rate found in the lower income families (because they received fewer transfer payments), they do face an unrelenting rate of tax in excess of 50 per cent. The commentary of the experts is largely sanguine about the high rate of tax on non-welfare recipients.

Figure 8 explores the EATRs on a median income family with a spouse with moderate skills who is considering entering the workforce. Only on very low hours of work do the EATRs fall below 40 per cent. Approaching full-time work, the EATR is solidly above 60 per cent. For these families, the problem is high tax rates, not welfare payments.

Figure 8: EATRs for a family with the father earning $1005 per week and the

the mother earning $20.00 per hour with one, two or three children -- one

child in child care at $4.30 per hour

Importantly, these are the families which are in the best position to add to the workforce in the future.

What to do?

It's simple really: welfare transfers must be reduced. That is the only way to solve the high EMTRs for lower income people and for medium-to-higher income people. And the only way to create incentives for people to remain in or re-enter the work is to cut welfare payments. The high rate of withdrawal of welfare is the cause of the high EMTRs for low income people, and the high income tax rates necessary to fund the welfare system are the cause of the high EMTRs for medium-to-high income families.

As shown by recent history, this can only be achieved by giving large tax cuts. If governments have money, they will spend it on politically sensitive, targeted voting blocks, including welfare recipients.

As shown in Table 1 the disposable income of people on the bottom quintile has grown by 18.5 per cent over the past 6 years -- most of the growth has come from increased welfare transfers with the level of welfare dependence increasing.

Table 1: Average real total income by income source for bottom quintile,

1997/98-2004/05

| 1997-98

$ | 2000-01

$ | 2004-05

Pre-

Budget

$ | 2004-05

Post-

Budget

$ | $ change,

1997 to

post-

budget

2004/05

$ | % change,

1997 to

post-

budget

2004/05

% |

| Wages and Salaries | 117.1 | 94.3 | 124.2 | 126.4 | 9.25 | 7.9 |

| Transfers | 353.6 | 398.4 | 401.0 | 423.1 | 69.51 | 19.7 |

| Other income | 7.8 | 9.8 | 13.4 | 13.9 | 6.13 | 79.1 |

| Total income | 480.4 | 506.8 | 546.2 | 571.5 | 91.1 | 19.0 |

| Total disposable income | 467.2 | 495.6 | 529.0 | 553.7 | 86.5 | 18.5 |

Note: Figures in the first four rows of this table refer to average

real total income from each source, not to disposable income.

Source: NATSEM calculations based on STINMOD/98A, STINMOD/00A, STINMOD/04A

As such, the barriers to moving from welfare to work have increased and the costs imposed on median and higher income taxpayers to pay for these transfers have increased.

An EIC in tandem with effective time limits on welfare payments and/or as a replacement for welfare transfers would be worth considering, though this would best be achieved by increasing the bottom threshold to as $12,000.

As to equity, what is equitable about the state extracting over 50 per of a person on moderate income?

LABOUR TAXES

I now turn to the second of the major themes I mentioned at the start of this address -- the question of labour taxes

In comparison to other countries, Australia does not have high rates of labour taxes -- indeed as officially measured, Australia has the lowest level of labour taxes in the OECD. Care must, however, be used in measuring these. Australian payroll taxes rates are low -- the maximum is 6.5 per cent and because of large-scale exemptions, less than 10 per cent of businesses pay the tax. According to the ABS, the average effective rate of payroll tax in Australia was 2.9 per cent of labour costs in 2002–03, down from 3.4 per cent in 1993–94.

By contrast, European countries characteristically impose very high rates of payroll tax, often in excess of 20 per cent, and with few exemptions. In the US, government (state and Federal) payroll tax averages around 18 per cent, again with few exemptions.

In Europe and the US, the proceeds of payroll taxation are earmarked for social expenditure such as pensions, unemployment insurance, retirement and other social expenditures which, in Australia, are funded out of income taxes. Initially, the Europeans and the Americans established these systems on an insurance or a funds format, where workers made contributions to meet the future costs of their own social liabilities, with access to these payment contingent upon contributions made.

Over time, however, eligibility rules were watered down, the funds were raided, and the insurance schemes loaded with extra costs. As such, the schemes are now essentially welfare schemes funded by payroll taxes.

The Europeans, in particular, are now stuck with very high payroll tax rates and a very generous and untied welfare system. These are proving impossible to sustain financially and politically difficult to pull back. They are also proving to be a large barrier to employment.

The US social security system, which is funded with the largest payroll taxes, is approaching bankruptcy, is not sustainable and major reform is in the wind.

The US and European high payroll tax approach is not a system which we should emulate.

While we are a long way from them, there are now pressures to move in that direction which should be resisted, most of these pressures are originating in the industrial relations system

There already exist a number of funds established through the industrial relations system ostensibly to cover redundancy, training, and long-service leave. These funds, as detailed in the Cole Royal Commission into the Building and Construction Industry, are often not used for their stated purposes, but instead to fund the managers. Unions currently have campaigns under way to increase the coverage of these funds across industries. At the last federal election the ALP proposed to introduce a comprehensive and mandatory redundancy scheme funded by a surcharge (a payroll tax in all but name). We can expect additional moves along this route.

Workcover premia, which are funded through an ear-marked payroll tax, have increased by 50 per cent over the last 8 years, from 1.5 per cent of labour cost (including wages) in 1994 to 2.2 per cent in 2002. The largest increase took place in NSW and the Northern Territory, where they increased by 100 per cent and 300 per cent respectively.

There are a number of reasons for the increase, but the dominant cause is that government and the courts are increasingly allowing welfare aims to be achieved through workcover funds. This is exactly what happened overseas and must be guarded against here.

We must also be concerned about the integrity of the superannuation system. Although it is far superior to those in place off-shore, the system remains very much under the control of politicians and powerful interest groups, such as the funds management industry. It took over 10 years before some degree of choice and portability of fund were allowed. The system has been increasingly attenuated by controls and regulations undermining its value to investors. There is growing pressure to restrict the use of funds. Moreover, the system remains highly taxed -- more so than in any other country.

In the future, as pressure grows on retirement payments, one can expect increasing attempts by politicians, as happened in the US and Europe, to use regulation to steadily nationalise the super scheme through regulation.

Indeed, great effort must be made to keep the super system out of the control both of politicians and their friends in the super industry.

Unless we maintain vigilance, the workcover, super levy and other labour charges will, over time, be converted into a large payroll taxes and l push us into the European morass.

INDEPENDENT CONTRACTORS -- PAYG AND INCOME SPLITTING

Finally, I shall now look at the third major theme I outlined at the beginning of this talk -- namely, tax and independent contracting.

One of the most resilient tax myths is that people become independent contractors as a tax avoidance and minimisation scam. And therefore that there is a substantial amount of tax revenue to be raised by closing down this loophole.

It is true that increasing numbers of people are leaving the master–servant form of employment and becoming independent contractors.

Recent research puts the number of independent contractors at 26.5 per cent of the total number of people employed in the private sector. A survey by the South Australian Institute of Labour estimated that the number of self-employed stood at only 3 per cent of the workforce in 1989. Although the two measurements differ significantly, I think one can surmise that there has been rapid growth in the numbers of independent contractors in both absolute and relative terms.

Much of this grow undoubtledly came at the expense of the unions. Over the last 15 years, the unionised workforce has declined sharply and now stand at just 17 per cent of the private sector workforce. In that sector, independent contractors are around 50 per cent more numerous than union members. The unions have waged, and continue to wage, campaigns to prevent the growth of independent contractors and thereby their loss of membership.

One prong to the campaign has been to use the Income Tax Act -- under the guise of stopping tax avoidance -- to close down or greatly limit the ability of people to operate as independent contractors.

Independent contracting does pose a major challenge for the ATO. Income tax was built upon the ability to collect tax at source from a limited number of employers on a pay-as-you-earn basis. Independent contractors complicate this because they are not employees, they often have multiple clients or revenue sources and they incur expenses in earning their incomes. Thus, they increase the number of collection points and complicate the measurement of taxable income.

The historical response of the ATO has been to restrict access to independent contracting status for tax collection purpose by defining them to be employees rather than businesses, thereby increasing their effective tax rate. That interpretation was supported by the labour movement, but often overturned by the courts.

As part of ANTS, the Howard Government specifically tried to address the tax-based bias against independent contracting through the development of the PAYG and ABN legislation. Under these:

- Common-law employees are caught within PAYG.

- Independent contractors who work through labour hire firms are caught within PAYG.

- Independent contractors who work directly and have an ABN can choose to be caught within PAYG by signing a "voluntary agreement".

- Independent contractors who do not wish to enter PAYG can remit their own income tax at source, but require an ABN if they don't want their client/s to withhold 48.5% of invoices.

This process is complicated and does impose substantial compliance costs on independent contractors. It is also designed to maximize pressure on all income earners to be within the PAYG system.

Nonetheless, it overcame the ATO problems with independent contractors, by ensuring that they pay their fair share of tax.

Another major concern with independent contracting is that it allow income-splitting.

Contrary to most accusations, large-scale income-splitting in the Australian community is unproven. In the only authoritative and detailed investigation done of income-splitting, the practice was shown to be minor.

During 1997 and 1998, the ATO conducted the "Alienation of Personal Services Project". An ATO status report of December 1998 showed the following:

- 65,000 taxpayers were profiled for investigation as likely income-splitters.

- 55,000 notices were sent to taxpayers initiating review of tax returns.

- 5,403 taxpayers were specifically targeted for tax review.

- 1,104 tax agents were visited in the taxpayer's review process.

- 714 taxpayers were issued adjustments notices.

- Percentage increases in tax paid varied from 1.9% to 11.6% per taxpayer.

An unspecified number of taxpayers were found to have overpaid tax and were entitled to a refund.

The additional tax raised was below that expected of a random audit of taxpayers' returns. The conclusion of the audit was that the vast majority of people structure themselves as a business for legitimate business purposes and not for tax purposes.

The audit is the only factual analysis of allegations of income-splitting ever undertaken in Australia, but oddly, has been given little attention.

Despite this evidence, in 2001, the Government released draft Personal Services Income (PSI) legislation based on the idea that income-splitting was extensive and that the only way to stop it was to tax independent contractors as if they were employees. Accordingly, it proposed a rule that people with 80 per cent of their income from one source would be treated for tax purposes as employees.

It took several months for the implications of this to be realised by the community and then a political storm broke. The PSI legislation was altered.

The final PSI legislation, passed in September 2001, comes back to core principles and uses the difference between the employment contract and the commercial contract as the defining distinction.

If a person earns income under an employment contract, they are taxed and treated as an employee.

If a person earns income under a commercial contract (an independent contractor), they are taxed and treated as a business.

The legislative wording that explains this is convoluted, but the core principle has been set.

None of this suggests that a person is permitted to commit tax fraud. The clear suggestion in the debate against independent contractors was that persons who sought to become independent contractors did so to avoid tax. The inference was that the process of an individual person earning income through commercial contract arrangements, of itself caused tax fraud. This was not a sustainable argument given the facts.

Independent contracting is an essential route to risk-taking and entrepreneurship. The interaction of the tax collectors and the industrial relations club has, for a variety of reasons, restricted its growth.

Recent legislative changes in the tax area have reduced barriers to independent contracting. The Howard Government has indicated that parallel reforms in the industrial relations arena are also in the making.

Tax and work is rightly a major focus of policy debate. We have, however, allowed the debate and policy to be driven and distorted by the overwhelming emphasis and interests of the industrial relations club.

If we are to address the real challenge -- to get more people into work, out of welfare and taking risk -- we must realign the debate.

The Howard Government has undertaken some useful reforms on the tax and independent contracting fronts.

But the big issue -- reforming the welfare/tax system -- has yet to really begin.

ENDNOTES

1. Duncan, I (2002) Promoting Employment through Welfare Reform: Lessons from the past, prospects for the future, The 2002 R I Downing Lecture Faculty of Economics & Commerce The University of Melbourne, http://www.ecom.unimelb.edu.au/iaesrwww/events/Duncan2002.pdf.