Occasional Paper

INTRODUCTION

Throughout Western Australia fundamental changes have occurred in the way private property rights are protected by law. The impact of these changes can be felt by home buyers struggling with excessive prices, farmers unable to profitably use the land and water they own, and miners increasingly hamstrung by land being locked away in conservation parks and reserves. Together they amount to a gradual, but significant erosion of traditional protections for private property rights.

This paper brings together what may appear on first notice to be unconnected regulatory intrusions into an exposition of the underlying diminution of property rights they all share. In turn, the Western Australian examples are contextualised within a broader discussion of the importance and nature of property rights, with special emphasis on the link between robust property rights and income. In summary, the paper argues that Western Australia has embarked on a risky path that is already resulting in negative outcomes.

FARMING

"Farmer Jim is thinking of felling one of the 20,000 trees on his property for fence posts. He has used up his 30 tree (0.15 per cent) exemption. He looks at one of the 19,970 remaining trees. He has to consider: what slope it is on; whether it is a rare species; whether it has any hollows or is on the way to having hollows; what native animals or birds are feeding off it or are likely to do so; what effect it has on the forest canopy; whether it is near a stream; whether it is of aboriginal significance; etc., etc. Then he will be in a position to make a lengthy submission to government seeking permission to fell". (1)

The operation of the various environmental protection laws, but especially the Western Australian Environmental Protection Act (1986) as amended in 2004, is increasingly restricting the capacity of farmers to farm their own land. (2) One particular aspect of the Environment Protection Act, the manner in which farming land is assessed for its environmental value, is critically flawed. Under current processes, the government sets regional principles of assessment and then assesses farming land in the region against those principles. Once assessed, any patches of native vegetation or wetlands are in effect ceded to the state since no development can then occur on them. Affected farmers can only appeal on the question of whether the assessment meets the regional principles. However, the consultation process only starts after the regional principles are adopted so farmers have no capacity to even know what the principles of assessment are until it is too late to change them. The WA Property Rights Association (WAPRA) and others have documented many instances of virtually entire farms being assessed as having high conservation value, and therefore unable to be farmed. Cruelly for the farmer, in almost every case the existence of the high conservation value area is as a result of the farmer voluntarily fencing off wetlands, planting trees and retaining hollow trees for habitat. In other words, the habitat has been reintroduced by the farmer's actions and at the farmer's cost, yet the result is the loss of control over that part of the land for no compensation.

When the Productivity Commission reviewed the national impact of native vegetation and biodiversity regulations, it found that the current approach is placing heavy burdens on landholders without compensation. Furthermore, the commission noted that "nor does regulation appear to have been particularly effective in achieving environmental goals -- in some situations, it seems to have been counter-productive". (3)

A major source of disagreement is the conservation value of swamps, river flats and bogs, now called wetlands. Once land is designated as wetlands it cannot be grazed or otherwise used productively, despite the fact that in many cases the land is often very fertile and good for grazing, and has been used this way for decades. In other cases, (4) private land on hills and nowhere near water is classified as wetlands, while nearby lower ground in public ownership is not. Apart from definitional issues over what is a wetland, there are additional problems created by the 200 metre wide buffer zones required around some designated wetlands. Depending on topography and property lines, the combination of wetlands and buffer zones can render entire properties legally unusable.

In all cases the problem is not so much that land is taken out of production -- often that is the only way to preserve high conservation areas -- but that it is done so with no recourse and no compensation. As farmers continue to hold title to the land no compensation measures are triggered. In extreme cases, "conservation covenants" can mandate maintenance and even improvements of conservation or landscape values, all without compensation.

HOUSING AFFORDABILITY

Housing in Perth is widely regarded as too expensive (5) and the cause is lack of supply. (6) Successive government policies have attempted to increase infill development at the expense of the new housing on the edge but have generally only been successful in limiting green fields development rather than also increasing infill consolidation. Many have argued that the whole premise of forcing infill is movement in the wrong direction as many families seek to own their own home, built to their specifications, in an area with other families doing the same thing. However, it is not necessary to have a preference for either infill or edge development to understand that lack of supply is the clear cause of house prices being so high that a family needs to earn one and a half times average earnings to buy a house.

Moreover, in Perth, land shortages cannot be blamed for the lack of supply. The city has ample land that is currently being used for agriculture that could rapidly be developed for housing. Instead, the cause of land shortages is planning policies, as well as taxes and charges that have resulted in a piece of land with planning permission being worth 100 times what the same piece of land is worth without the permission to build. At the same time, property owners with land adjacent to Perth, but not designated as useable for housing, are unable to use their land for its best use, which is to subdivide it for housing. So while the current system delivers huge windfall profits to those fortunate enough to own property that receives subdivision approval, other owners receive nothing, the end buyers pay well over the unrestricted price and many others are denied the choice to buy a house at all because they are all priced out of reach.

The distortion of Western Australia's property markets through the design and implementation of the planning system has occurred over a long period. Western Australia was the first state to pass a planning act in 1928 (after thirteen years of argument before it passed through parliament). The scope of the planning scheme has continuously expanded to the current point where even the most minor alterations and additions require planning permission. Each of these rules reduces the right of owners to use their property as they wish and are therefore a diminution of property rights. It is not feasible to repeal all this legislation as too many investment decisions have been made on the basis of it. However, the deficiencies of the approach are manifest and growing.

In more recent times, the introduction of conservation schemes such as Bush Forever, Conservation Wetland Buffer Zones and Biodiversity Reserves, are removing from future development large tracts of land in attractive development areas. For example in the south west corridor some 26,000 Hectares are now locked away in these reservations. (7) While ensuring areas of high conservation value are not lost forever due to inappropriate development, it is becoming increasingly evident that these schemes are in some instances being deliberately used to limit the ability of landholders to provide more lots for housing rather than primarily for conservation.

MINING

Throughout history, mining has been a focal industry for the formal and informal allocation and management of property rights. During the Californian gold rush, miners set up their own registry of titles and set their own rules for claim size and operation. In the absence of a functioning state, the miners developed a set of rules which worked so effectively that a miner could leave his marked claim for days to get supplies and return to not only find the claim untouched, (8) but also his valuable tools untouched. The story of the Ballarat miners and their revolt against excessive taxation and other infringements on their rights to mine is iconic to generations of Australians. (9)

As the major driver of economic prosperity in Western Australia, it is of utmost importance that exploration and development of new ore bodies is not stymied by archaic or intrusive regulation. Two unrelated problems highlight some of the issues facing mining that are caused by a failure to properly take account of property rights.

The first is the operation of the WA Warden's Court, or more specifically, the failure of successive Western Australian governments to properly resource the Wardens' Court and to reform its operation. The Warden's Court hears matters relating to mining tenement applications, objections and forfeiture, as well as civil matters related to mining. It is unusual in a number of respects. Firstly, it has both administrative and judicial functions, (10) and the administrative functions are enabled through wardens making recommendations to the Mining Minister; or an odd arrangement that has the potential to compromise the independence of the court. Secondly, there is no right of appeal for many of the types of decisions wardens make. This has led to the use of judicial review in the form of prerogative writs of decisions. Such review can only be on the technical question as to whether the court has acted outside its jurisdiction, not on the merits of the case. Lastly, although a section of the Magistrates Court, the Court of Wardens has the right to rule on matters worth hundreds of millions of dollars, amounts more usually seen in much higher courts.

Apart from an antiquated and arguably defective structure, the Court also suffers from the problem of resourcing. Wardens are also Magistrates, and the operation of the Warden's Court takes a secondary position to the needs of the Magistrates Court. In practice, this means the Warden's Court may only sit for one day a month, making it impossible to get consecutive hearing days and dragging out cases over years. (11) In February 2007 the backlog of mining tenement applications peaked at 18,700 yet, it was not until August that a small amount of additional funding was announced. (12)

The effect of the deficiencies of the Warden's Court is to create uncertainty over mining claims. Without a settled title to a claim miners are unable to raise capital to get their project off the ground. This has particularly harsh effects for junior miners without other projects that can be used as collateral.

Another current problem for miners is the classification of former pastoral leases as conservation parks. In September 2007, the State Government announced the conversion of a further 5.5 million hectares of pastoral leases to parks and nature reserves. While conservation park status does not ban mining or exploration, it changes the default position to no mining which then has to be appealed to the minister on a case by case basis. (13) In practice ,this means that existing mining operations are allowed to continue while new exploration and undeveloped tenements face additional hurdles. The Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) is open in pursuing this approach to restrict further mining in areas already being mined, such as Portland Mining's operations in the Mount Manning region. (14) In a similar case, centred on Mount Gibson, the project was allowed to proceed, but only after 32 appeals against EPA decisions were successful. (15)

Both the Minister for Mining and the EPA have been criticised by Ian Loftus of the Association of Mining & Exploration Companies for constantly changing the rules:

"For example, Cazaly Resources had a tenement ... but the government took it off them. The Mid-West Corporation had an agreement, which they used to raise capital, but the Minister wrote to Mid-West and told them they were going to get rid of it. ... There's 1200 separate mining tenements on that land and each one of those tenements is jeopardized by government extending the conservation area". (16)

For miners, the classification of mineral rich land as a conservation park after it has been pegged for mining is a clear change in the value of the land. While the resource under the ground remains the same, the cost of extracting the resource has increased due to the additional processes and appeals required. The right to use the land is diminished. This could be of a net value if the conservation value of the land is such that its preservation outweighs the additional costs. However, in the current case the land is former pastoral leases with only very small plots with high conservation value. The lack of real conservation value is demonstrated by the overturning on appeal of every case appealed against. However, this process is costly and time consuming, and often outside the capacity of small companies to undertake.

The boom in mining and exploration in Western Australia is obscuring the real problems the industry is facing, as the government fails to consider the impact on new projects and the attractiveness of the state for additional investment, by the persistent curtailment of property rights in the mining industry. The situation where land of low conservation value is designated as a park, thereby adding additional layers of complexity to attempts to mine it, but not actually stopping mines, seems to have little logic. If areas of high conservation, as determined by scientific experts, were locked away from mining but the rest was allowed, more land would be conserved, as the mining industry would concentrate on the vast areas permitted, rather than the current situation where everything is targeted as high and low conservation is not properly designated. This is another case of the poor application of the principles of property rights leading to both poor environmental outcomes and poor commercial ones.

WHY PROPERTY RIGHTS MATTER

It is a mistake, often made by those ambivalent or opposed to capitalism, to equate property rights with financial gain; as though the importance placed on strong property rights is a smokescreen to obscure the interests of the rich elites. Yet such a reading is profoundly wrong. Instead, a system of strong property rights offers the greatest benefits to the poorest members of society and is the foundation of a free society.

Hernando de Soto, a Peruvian economist, tells the story of some consulting he did in Indonesia. De Soto noticed when he walked through the rice fields a different dog would bark as he entered each property. The rice farmers had to rely on barking (and biting) dogs for protection because they held no legal title to the land. Compared to a system based on records, titles and shares, dogs, fences and guards are expensive and inefficient methods of protecting the land and crops.

As de Soto notes, "with titles, shares and property laws, people could suddenly go beyond looking at their assets as they are (houses used for shelter) to thinking about what they could be (security for credit to start or expand a business)". (17) It is this fundamental change from forcibly defending occupation to a legal right that forms the basis for the capitalist system. Property rights are therefore not only about ownership, they are the basis of credit, banking and entrepreneurship. Indeed, property rights are the basis of a free society.

As Gerry Eckhoff, the former New Zealand MP said, "our property rights are almost subliminally recognised by the public, banks and commerce. Most importantly, they are a legally enforceable transaction. This legal system is hidden deep within the property rights concept. It's this system that allows us to transform ourselves from mere squatters to landowners, or perhaps more correctly, right owners". (18)

Unfortunately, it is the very fact that property rights are the foundation, rather than the parapet, of the legal system and free society that often obscures their role and makes easy their erosion.

THE RIGHT TO TRADE PROPERTY: ABU DHABI As neighbouring Dubai boomed, Abu Dhabi stagnated. Despite Abu Dhabi sitting on the most oil in the world, little of the wealth generated was invested back into development as the oil barons preferred to buy property in Western capitals where they knew it could be resold. There was no private property ownership in Abu Dhabi, the capital of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) before August 2005, when UAE nationals were permitted to own land and land registration was created. And until February 2007, foreigners were banned from owning property in Abu Dhabi. Then, in a further relaxation of the law, the President allowed foreigners to own buildings (but not land) in specified investment areas. Further, non-UAE nationals were permitted to lease land on 99 year leases. Prior to the land reforms, all attempts to diversify the economy from oil failed dismally, and little new building was undertaken. The results of creating property rights have been spectacular and immediate. Just one of the multiple projects currently being built "will feature 36 mixed-use towers, two shopping malls, two mosques, and a five-star hotel. On Al Reem Island, Shams Abu Dhabi will have a canal system like Venice's, a central park like New York City's, and an 83-story skyscraper". (19) Already opened is a US$3 billion hotel, where basic rooms cost US$1,000 a night and the city has now attracted the first branch of the Louvre.  |

PROPERTY RIGHTS AND INCOME

The twentieth century saw many experiments in the effects of the total removal of property rights. Despite the common result of these experiments -- totalitarian states with recurring widespread hunger and depredation -- a number of states continue to forcibly remove property from groups they are opposed to.

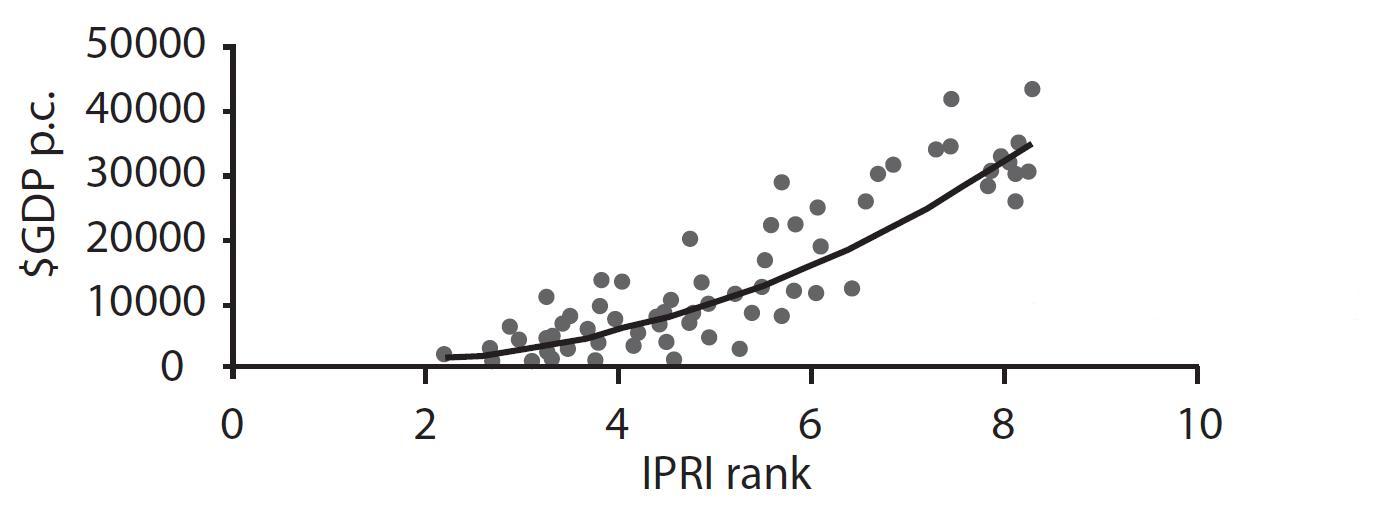

However, totalitarian states are not alone in restricting property rights. All modern states restrict the property rights of their citizens to some degree. And we can demonstrate a link between the level of protection a state gives property rights and the level of poverty in that state. The 2007 International Property Rights Index measured the strength of property rights against a wide range of indicators and found a strong correlation between property rights and income.

Table 1: Strength of Property Rights & Relationship to GDP

| IPRI quartile | Ave. GDP per capita |

| Top 25 per cent | $32,994 |

| 2nd quartile | $15,679 |

| 3rd quartile | $7,665 |

| Bottom 25 per cent | $4,294 |

Source: IPRI 2007 Report, p. 31

The clear causal relationship between strong property rights and income has important lessons for developed societies. Property rights deliver the foundations of the wealth enjoyed in developed societies. If such societies are to continue to prosper, close attention must be paid to maintaining robust protections of property rights.

Chart 1: International Property Rights Index and Gross Domestic Product per capita Source: IPRI 2007 Report

Source: IPRI 2007 Report

WHAT RIGHTS ARE PROPERTY RIGHTS?

Property rights are not a single, unitary right, but a bundle of rights relating to property ownership. They include the right to own property, the right to dispose of property and the right to exclude others (also known as the right to "enjoy"). Another way of looking at property rights is to think of them as the right to control property (by stopping anyone else acting against your wishes) and the right to title (the reasonable belief that others understand it is yours to control, even when you are not in possession).

Contemporary property rights mean owners have the right to obtain economic benefits from their property, whether by using it, renting it out or selling it. The extent to which these rights exist is a product of the existing law supported by social customs. The limit of ownership, that is, what owners can and cannot do with their property has always been circumscribed. Nevertheless, traditionally the limitations placed on property owners were intended to overcome obvious problems that impacted either neighbours or the wider society. For example, hunting every bird and animal until none remain has been banned by regulation for over 1,000 years. (20) However, what constitutes fair use of private property, and which externalities the society has the right to intervene with are challenging problems. In recent years the level of regulation of property has escalated, often stripping owners' rights unfairly to the extent that, for many property owners, a substantial part of the value of their investment has been destroyed.

Everyday, every Western Australian makes decisions only possible because of property rights. Yet, often the link between security of general property rights, and security for the ones a particular individual exercises is not made clearly. As a result, the first home buyers getting their first mortgage are unlikely to ever consider the role their security of title plays in their ability to get a mortgage. Moreover those same first home owners are even less likely to link their property rights to that of a mining company or a farmer. Yet, if the government alters the rights of one group, perhaps because they are relatively small in number, then it can reduce the rights of all.

THE RIGHT TO ENJOY: CELEBRATION, FLORIDA Property rights are often voluntarily forfeited by aspiring homeowners in "gated communities". The town of Celebration in Florida is a planned community constructed by the Disney Corporation. Through the use of covenants, easements and servitudes, a set of rules property owners must abide by have been created that restrict what all owners can do with their properties. There are limitations on house styles, colours, fences, outside blind styles and a myriad of other requirements. House prices in Celebration are higher than comparable suburbs without the restrictions. What does a themed community where people voluntarily restrict their own rights have to do with the right to enjoy? At Celebration, home owners gain the guarantee of their aesthetic preference. In other words, people who buy there like the style and are prepared to pay extra to make sure all their neighbours like it too. As Andrew Morriss, a law professor at the University of Illinois, said "Celebration increased the value of the bundle of rights each person purchased because it added rights worth more (the ability to prevent an aesthetic disaster down the street) than it took away (the ability to create one's own aesthetic disaster)". (21) The legal instruments of covenants and easements are the enforcement mechanisms when something goes wrong. However, they are rarely used. The market mechanism of higher prices for these houses results in only people attracted to the rules buying there. It is a virtuous circle of additional value created by codifying the right to enjoy.  |

WHAT THE EROSION OF PROPERTY RIGHTS LOOKS LIKE

As recently as 1962, the High Court of Australia held that landowners possessed the "proprietary right to subdivide without approval". (22) Western Australia has changed a great deal since then. Now, only tracts of land zoned for housing may be subdivided and there are additional highly prescriptive rules governing the number of blocks per hectare, local and regional open space set-asides (23) and, increasingly, requirements for the provision of other services to the subdivided blocks. Compared to this labyrinth of planning law in operation nowadays, the idea a property owner could subdivide at will is remarkable. With the clear relationship between Perth's unaffordable housing and lack of supply of new housing lots, (24) the effects of placing such high barriers to subdivision are painfully obvious.

How Western Australia went from no restrictions on subdivision, to a situation where neither the farmer who tries to sell off a surplus house nor the suburbanite wanting to subdivide her quarter acre block can do so without intricate planning permission to subdivide, was not a single event. Similarly, the rise of heritage legislation and council rules has been a disjointed set of fits and starts, often in response to an egregious act. Little by little, what seem to be reasonable restrictions to stop someone pulling down an important building, or to stop a five story strata titled block of flats on a suburban block, or to stop a farmer obliterating the last remnant of forest to install an irrigation system, are added to the statute books.

Most people believe themselves to be personally unaffected by each encroachment and may even agree that old buildings should be preserved, or flats should not be built in suburbs with predominately detached housing or, that native vegetation should be protected. For many people, citizens and legislators alike, the first response is to ban whatever the perceived problem is. However, that approach inevitably results in a diminution of all property rights because every time a new restriction is enacted without compensation the door is left open for further encroachments.

These regulations are not costless. The value of people's and firms' wealth is reduced every time a new regulation is passed which restricts the ability of property owners to use their property to the best advantage. For example, the introduction of height restrictions in an area, perhaps as a result of a particularly large building being proposed against existing residents' wishes, takes away the capacity of all property owners to redevelop their property as multi-story flats. However, when there have been only few of these laws passed without affecting that many people, both bureaucrats and the general public forget about the private costs, and focus on the supposed public benefit. (27)

Paradoxically, the cheapest, most effective and fairest way to deliver the outcomes being mandated in much of the pernicious creep of takings perpetrated by all levels of government against property owners is to strengthen property rights. As the example of Celebration, Florida showed, with strong property rights, an outcome desired by a community can be delivered in a way that adds value to the entire community. The key is a legal structure that allows investors to buy property with its uses clearly defined and incorporated into the price. Moreover, when community attitudes change so that previously accepted practices are no longer supported, for example demolishing very old buildings, then the community can achieve their new goals through appropriate financial payments to existing owners to comply with new restrictions.

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION: SUSETTE KELO AND GRAHAM HARDIE In 1996, Susette Kelo, a nurse and recently divorced mother of five, moved back to the town she grew up in. Ms Kelo bought and renovated an 1893 cottage on East Street, Fort Trumbell. The daughter of factory workers, Ms Kelo describes herself as "about as ordinary as you can get". However, she has ended up as the public face of eminent domain -- the name used in the US for compulsory acquisition of property.  Her small pink house became the centre of a string of law suits, which went all the way to the US Supreme Court, arguing over whether the city council could compulsorily acquire her property to sell to a private developer as part of a plan to revitalise the area. Unlike Australia, where property has always been able to be compulsorily acquired by the state (including local government) for any purpose, in the US, governments were limited to only compulsorily acquiring property for public purposes. The argument in the Kelo case was over whether compulsory acquisition for private purposes that would result in higher economic activity and taxes paid was legitimate. In a highly controversial decision the Supreme Court split 5 to 4 against Susette Kelo, forcing her to move. (25) In 1986, ten years before Susette Kelo was buying her cottage, Graham Hardie started putting together his property on the corner of Roe and Lake Streets, Northbridge. At the time Northbridge was pretty down at heel, a rough and often dangerous place to be, especially at night. Now, of course, Northbridge is the thriving and increasingly fashionable entertainment, dining and residential neighbourhood with a prime position close to Perth's CBD. And Mr Hardie has spent the past six years developing plans to further enhance Northbirdge with a mixed use residential and shopping complex. In late 2006, the Western Australian State Government announced that it was compulsorily acquiring Mr Hardie's land to build a police complex, Magistrate's Court and watch house. (26) The announcement bought strong condemnation from many Perth leaders including the City Council, the Property Council and the WA Chamber of Commerce and Industry. However, there was no possibility of a legal challenge because there are no limitations in Australia over compulsory acquisition, and anyway, the police complex was clearly for a public purpose, even though it was clearly not the best use of the site. The public pressure was effective; in July 2007 the State Government backed down and announced it would locate the police complex on government land in Northbridge. Despite the differing outcomes and purposes for which the compulsorily acquired land was to be put, the cases share one profound similarity; the ease with which elected officials and their bureaucrats decided that the best outcome was to compulsorily acquire land. In both cases other options could have been pursued. In the Kelo case, many of her neighbours were pleased to sell their properties to the council, but her house and other objectors were close to the edge of the site where development could have occurred without forcing her to move. In the Hardie case, the WA government owned hectares of land in and around Northbridge suitable for the police complex, a fact confirmed by the eventual location of the complex on government land. Public opinion towards both decisions was overwhelmingly negative; in the US the Kelo decision has proved so unpopular that most states have subsequently changed their constitutions or enacted laws to stop it happening again. In Perth, the government backed down, thereby taking the immediate heat out of the call for law reform.  |

ROLE OF THE STATE IN THE PROTECTION OF PROPERTY RIGHTS

Westminster tradition, King John's 1215 acceptance of his baron's demands to restore the properties he had confiscated, is remembered as the historic beginnings of limits to capricious action by the Crown. From this period also comes another key milestone in the development of property rights, the doctrine of due process.

The promise by the English crown that no free man shall be deprived of his life, liberty or property subject to the law of the land is one of only three clauses of Magna Carta still in legal force in the UK.

"No Freeman shall be taken or imprisoned, or be disseised of his Freehold, or Liberties, or free Customs, or be outlawed, or exiled, or any other wise destroyed; nor will We not pass upon him, nor condemn him, but by lawful judgment of his Peers, or by the Law of the Land". (28)

The two restraints agreed to by King John, namely that the crown cannot grab private property without compensation and that all people are entitled to be judged by the law of the land, were instrumental in the development of property rights. Together they form a strong defence for the weak against the strong. In the first case, the protection is against the strongest of all, the crown or government, and in the second against more powerful citizens.

Over time a coherent and large body of law grew up in England which enshrined and explicated the fundamental principles of property rights. In the succeeding centuries since Magna Carta protection of property rights became more entwined with ideas of individual liberty and limited government. Later other countries such as the US and Australia inherited these same traditions. In the US, for example, the 1788 Constitution referred to the people's "rights as Englishmen" which predominately meant a continuation of English property rights.

The US has been at the forefront of codifying law to protect property rights as fundamental to the protection of individual liberty. Perhaps most notable amongst these codifications is the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution which directly echoes clause 29 of Magna Carta.

"No person shall ... be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation".

The Australian Constitution echoes these sentiments when it restricts the Federal Parliament to only acquiring property when compensation is paid.

"The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to ... the acquisition of property on just terms from any State or person for any purpose in respect of which the Parliament has power to make laws". (29)

However, as this paper will argue, the effectiveness of this provision has been limited by High Court interpretations. In addition, no other level of government in Australia has this restriction on its actions.

CONTROLLING THE CROWN

"In the free and open society, the organized force of government is to be used only if necessary to protect the lives and property of peaceful individuals". Paul L. Poirot

Without specific controls, the State, as the most powerful entity in society, has the capacity to behave both capriciously and excessively. As the International Property Rights Index shows, such actions reduce the wealth of the entire society as well as being highly correlated with human rights abuses.

In Australia, despite there being no Constitutional bar to states and local councils totally expropriating property without paying compensation, this is not the most pressing problem. Conventions exist such that governments pay compensation, although the basis and amount of that compensation is often disputed. For example, it is common for property being compulsorily acquired to be valued at its current use even if the land has the potential to be put to a much higher value use. This becomes especially problematic when government is proposing an urban renewal project on a blighted site. However, total expropriation, to the extent that title is extinguished, is not necessary to destroy value. None of the examples in this paper involve the state taking all rights to a property without compensation. However, to concentrate only on that type of case is to miss the much more prevalent effect of government regulation reducing property owner's rights while still leaving her name on the title. Moreover, the amount and determination of compensation payable, even in cases of total expropriation, are also key issues which need urgent reform.

The legal basis for property rights is of utmost importance in societies built on the rule of law. However, in the classical liberal tradition property rights are natural rights which exist independently of the law. This is perhaps best enunciated by Frederic Bastiat,

"Life, liberty, and property do not exist because men have made laws. On the contrary, it was the fact that life, liberty, and property existed beforehand that caused men to make laws in the first place". (30)

In Australia, the High Court has moved away from the notion of deep or fundamental rights and has done so specifically in relation to property rights. The court has held that in the matter of compensation for expropriation, governments are completely entitled to legislate the amount of compensation even if it is manifestly inadequate. In a recent speech Justice Michael Kirby went to some lengths to explain the court's current position and to contrast it to other legal systems operating in the Westminster tradition. It is worth quoting him at some length to better understand how the court now embraces a strict interpretation of the constitution and rejects the doctrines of common law as this has profound implications for persons and companies seeking any remedy against state and local government laws.

"Further cases, decided in Australia in 2004, may be mentioned to show the current approach of the High Court of Australia to "deep” or "fundamental” rights lying outside the Australian constitutional text. They are, I will suggest, discouraging to the notion that the law, and the judiciary, will hasten to the assistance of people where their "deep” or "fundamental” rights are denied.

Although sometimes judicial relief is given, it is a comparatively rare event. Far from embracing Lord Cooke's concept about inalienable fundamental or "deep” rights, the trend of decisions in Australia at least, must now be seen as generally unhelpful to such protection. This is so whether by way of elaboration of the constitutional text or by invoking the doctrines of the common law". (31)

In practice, what this means is that the court will not provide protection to those who find themselves fighting against an unjust determination of compensation for the loss of their property. Nor is it likely to accept an attempt to argue that legislation which in practice removes rights, but in letter retains title, makes its victims entitled to compensation unless the legislation explicitly allows for compensation.

With the High Court effectively dealing itself out of traditional property rights disputes, the only avenue left to remedy the problem of regulatory takings spiralling out of control is through amending the Western Australian Constitution to mandate compensation at the rate of best use for land owners when land use restrictions reduce the value of their property by excision of existing rights or when the government wants to compulsorily acquire property.

REFORM AGENDA PRINCIPLES

The scope and size of the regulation affecting property owners allocates substantial powers to quite junior bureaucrats who may interpret the same provision in different ways. Particularly problematic are differences across local government in the interpretation of heritage laws and inadequacies in the number and specialisation of magistrates sitting in WA's Wardens Court of mining disputes. (32) Similarly, some farmers have faced inordinate delays in receiving answers to applications in relation to clearing native vegetation, and inconsistent advice through the process. Lastly, accusations of favouritism and even corruption continue to bedevil a small number of councils in relation to development approvals.

The growing arbitrary nature of much of the administration of laws which impugn property rights is a problem in itself and one not easily remedied by more or different regulation. Similarly, piecemeal reform to attempt to address a particular problem is an inadequate response to a systemic problem.

This paper recommends the adoption of a system based on four principles: compensation, consistency, openness, and right of appeal.

Compensation

At a minimum the WA constitution should be amended to match that of the Federal constitution to pay just compensation when property is taken from private landholders by the government. However, regulation often reduces the value of property without actually changing title, so the law needs to go further. An appropriate protection for property owners would be legislation with constitutional effect which requires the state to compensate land owners when land use restrictions reduce the value of their property by excision of existing rights.

Such a measure would have the added blessing of providing a financial incentive that it does not now have to the government to prioritise its heritage, environmental and water use goals, concentrating on the most important.

Consistency

All existing legislation needs to be reviewed to introduce consistency for how landholders are treated by all levels of government. The review will need to include planning laws, water entitlements and use, mining tenement law and its administration, native vegetation laws and any other aspect of Western Australian law which affects private property ownership and use.

Legislation arising from such a review will;

- require all state government departments and local government to apply a uniform process to detail any actual harm or public nuisance that proposed regulations are designed to stop or prevent, the extent to which they affect private property owners, and whether the goals of the proposed regulations can be achieved using less prescriptive means, such as voluntary programs,

- introduce mandatory benefit-cost analysis of proposed regulation using a standardised framework across government which values economic, environmental and, where possible, social benefits and costs from proposed property regulation. No legislation is to be enacted without the results of such analysis being made public for an adequate time period,

- prohibit state and local governments from using their compulsory acquisition powers to expropriate private property for private development in order to generate more tax revenue, and,

- prohibit non-legislative policies which have the effect of placing restrictions over the use of private property. All limitations on private property must be legislative and open to usual accountability mechanisms. Property owners who believe non-legislated mechanisms are adversely affecting them should have access to appeal mechanisms.

Openness

All government agencies, including statutory authorities, must be required to contribute to a central database, operated by the Valuer General, of any covenants, heritage listings, environmental restrictions or other listings which place restrictions on individual properties, including heritage overlays of entire suburbs. Landowners and potential purchases must, at a minimum, be able to easily, and at low cost, discover what they can and cannot do to their own property.

Right of Appeal

Establish a Private Property Tribunal to rule on the reasonableness of compensation paid by government to private property owners when their property is expropriated or devalued due to restrictions.

CONCLUSION

Western Australia has the natural resources to deliver an enviable standard of living for all its citizens. The current economic conditions are such that sub-optimal policies, which demonstrably destroy wealth, are obscured by the extraordinary growth from the mining boom. This paper has concentrated on three areas where the erosion of property rights are affecting either large numbers of people, viz housing affordability or important export industries, namely mining and agriculture. However, the erosion of property rights, and the concurrent rise of regulation as the first option to address a perceived problem, can be identified in many other areas. For example, heritage listings that place all the costs and restrictions on existing property owners supposedly to benefit the aesthetic preferences of society. Another example is the continuing vexed problem of how native title is constructed; bring few benefits and certainties to aboriginal people while simultaneously limiting investment over vast tracts of land.

These examples share a reduction in the rights accorded to property owners, often in the name of promoting community values such as heritage and environmental conservation. Paradoxically, by using punitive regulations which bring no benefit to existing owners, often the results of regulation are the complete opposite of the intention; for example, when a listed heritage building is allowed to decay until it is condemned or a farmer refuses to plant a single tree for fear of a future assessment of conservation value.

The development of property rights has a long and important history. The evidence is irrefutable that the protection of property rights is the key to wealth accumulation and secure and stable societies. Western Australia has the capacity to better protect its future prosperity, and to enhance it by implementing a much stronger protection of private property rights than now exists.

REFERENCES

1. Jim Hoggett, "The Death of Rural Freehold Rights", Review 54, no. 4 (2002).

2. See for example, Pastoralists and Graziers Association, Submission to the Department of Conservation and Land Management on Discussion Paper: Towards a Biodiversity Conservation Strategy for Western Australia (2005)., Richard J. Wood, Public Good Conservation -- Impact of Environmental Measures Imposed on Landholders (2000), Submission to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Environment and Heritage Inquiry.

3. Productivity Commission, Impacts of Native Vegetation and Biodiversity Regulations (2004), Inquiry Report.

4. See the WAPRA website for an example of this at Canning Vale.

5. Mike Nahan, "Waking up to the Great Australian Nightmare", The West Australian, 7 September 2006, p. 9.

6. Richard J. Wood, Fixing the Crisis: A Fair Deal for Homebuyers (2006).

7. Western Australia Property Rights Association, "Unaffordability and Government Policy", WAPRA Newsletter (2007).

8. Andrew Morriss, "Miner, Vigilantes, and Cattleman: Property Rights on the Western Frontier", The Freeman (2007).

9. Ron Manners, Keynote Address: Erosion of Property Rights Would Appall Ballarat Diggers. Paper presented at 150th Anniversary of the Eureka Stockade, 4 December 2004.

10. Wayne Martin, Paper presented at AMPLA Inaugural Warden's Court Dinner, 13 November 2007.

11. Marsha Jacobs, "WA Court Fails to Keep Pace with Miners", The Australian Financial Review, 6 July 2007.

12. Kate Haycock, WA Government Promises Funding to Clear Applications Backlog (MiningNews.net, 31 August 2007, accessed 15 November 2007).

13. Alex Forrest, Land Reclassification Another Hurdle: AMEC (MiningNews.net, 20 July 2007, accessed 15 November 2007).

14. Colin Jacoby, AMEC Calls for Cool Heads over EPA Decision (MiningNews.net, May 15 2007, accessed 15 November 2007).

15. Colin Jacoby, Future of Mid-West Mining Uncertain: AMEC (MiningNews.net, 3 August 2007, accessed 15 November 2007).

16. Haycock, WA Government Promises Funding to Clear Applications Backlog.

20. In medieval times all game was the property of the sovereign and landholders were required to gain a grant of free warren to hunt.

21. Andrew Morriss, "The Economics of Property Rights", The Freeman (2007).

22. "Lloyd V Robinson", (CLR, 1962).

23. Coalition for Property Rights, Property Rights under Attack in Western Australia (2004), Discussion Paper.

24. Richard J. Wood, Fixing the Crisis: A Fair Deal for Homebuyers.

25. Andrew Napolitano, "Property Rights after the Kelo Decision", Imprimis, January 2007.

26. Graham Hardie, Northbridge Deserves Better (2007, accessed 23 November 2007).

27. Richard J. Wood, Property Rights in Western Australia: Time for a Changed Direction (2006), Occasional Paper.

28. The National Archives, Magna Carta Translation: A Translation of Magna Carta as Confirmed by Edward I with His Seal in 1297 (US Natioanl Archives and Records, accessed).

29. "The Australian Constitution", in Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act (Australia: 1900).

30. Frederic Bastiat, The Law, ([1849] 1998).

31. Michael Kirby, Deep Lying Rights -- a Constitutional Conversation Continues. Paper presented at The Robin Cooke Lecture 2004, 25 November 2004.

32. Jacobs, "WA Court Fails to Keep Pace with Miners".