Address to H R Nicholls Society's XXIII Conference

The Changing Paradigm: Freedom, Jobs, Prosperity

23 March 2002

CENTRAL ISSUES

The central issues are how to reduce the costs of injury. Particularly important in this task is bringing into accord the incentive structures of the various participants so that they each reinforce one another in pursuit of these goals.

Essential in this incentive structure is the need to avoid the familiar insurance concerns of:

- moral hazard, whereby parties have little interest in acting in the best interests of the community as a whole and, indeed, may have an interest in acting in ways that detract from that interest; and,

- adverse selection, whereby parties have perverse incentives to select themselves into lower risk categories, opt out of coverage or classify their employees as falling within other jurisdictions if they consider the costs discriminate against them.

There is considerable capacity for political intervention in a mandatory insurance system. As with other such areas, the best approach would see premiums set so that the true costs are sheeted home as accurately as possible to the parties in the best position to take action to ameliorate these costs.

Ensuring the price and other elements of the incentive system works to promote efficiency is of relevance to the different stakeholders and the premium design is the crucial element in:

- employers ensuring the right amount of effort and expense is incurred to reduce the costs of accidents to the firm and the community

- employees ensuring that they take sufficient care in the work environment

- agents taking actions to assist in claims reductions; agents are the first line of assessment and the sales and processing arm of state systems like those in Australia but can have different incentives if their remuneration structure is not aligned with that of the state systems' interests

- removing any incentive of assessors to be indulgent in the sick notes they provide, out of sympathy with the injured employee or simply to avoid losing a client

- avoiding offering incentives for the employee to feign injury or, when injured, to remain off work longer than necessary

A low cost market-oriented compensation scheme is a significant element in the competitiveness of a nation and particular state. New ventures in particular examine the costs of each location where they have discretion in their location decision–Virgin Airlines is a recent example.

I want to pursue three themes today.

- What are the trends in worker injuries and insurance costs?

- How does compulsory and essentially no (worker) fault insurance fit into our preferred market structure? Where does it stand with the common law?

- How can incremental changes to the present system reduce costs and levels of injury

I won't address the safety and industrial relations issues that interface with workers' insurance except to say that:

- they are clearly means of bringing on a blue as seen in Victoria's Royal Commission into the building industry

- Victoria's Manslaughter Bill puts added pressure in offering union representatives more influence in the management of firms; some would argue that the present round of graphic advertisements for WorkCover, most of which point to employer culpability for deaths, are a softening up process to this end; there is no evidence to support this but a government controlled entity is always vulnerable to political pressure and this is all the more reason to shift WorkCover more comprehensively towards the private sector.

TRENDS IN WORKER INJURIES AND INSURANCE COSTS

Injury at work amounts to about 15 per million hours worked. The measure of Disability Adjusted Life Years puts work injury at a level massively below obesity, or lack of fresh fruit to say nothing of smoking and alcoholic consumption. It is in fact slightly more prevalent as a cause of mortality or morbidity than unsafe sex.

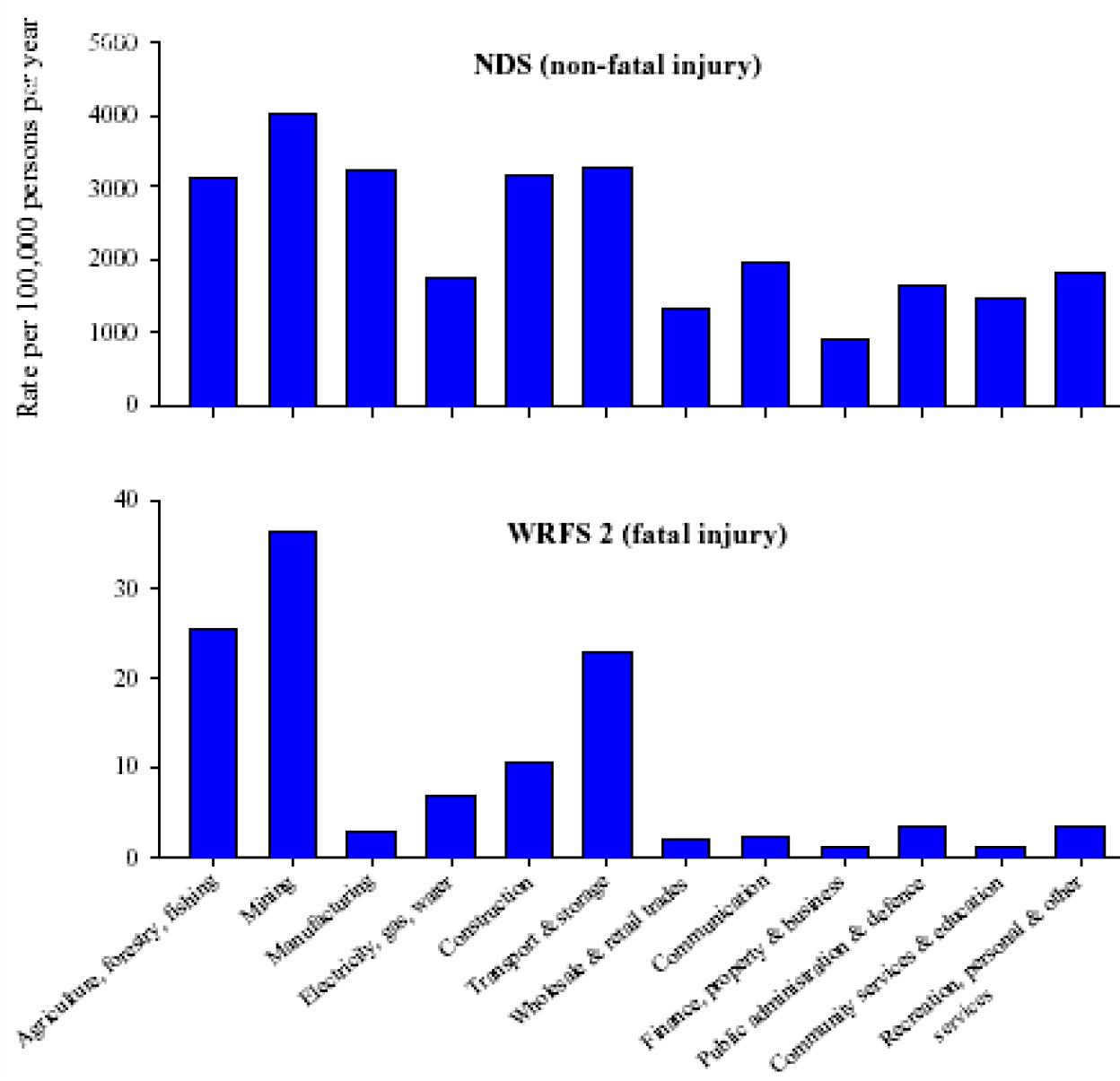

Work related deaths from injury are put at about 5.5 per 100,000 workers with about another 4 per 100,000 through disease. (1) By industry, fatal injuries are highest in farming, mining and transport. Non-fatal injuries are also highest in these industries and in manufacturing and construction. The following table illustrates this.

Source: Data on OHS in Australia, The Overall Scene,

National Occupational Health and Safety Commission October 2000, Sydney

If non-fatal illness is added to injury, the rates rise in relative terms for public administration, community services and education, and fro recreation, personal and other services.

These figures refer to 1995. The mining industry's injury rate has in fact halved since then. Indeed, the minerals industry "lost time injury frequency rate" fell from 70 per million hours in 1988/9 to 15 by the end of the 1990s

Injury rates have in fact been declining markedly. Victoria has seen hours lost per million-worked fall from about 25 at the start of the 1990s to 12 by the end. Other States have fared similarly: SA 32 to 15; NSW 24 to 19; Queensland 28 to 16; Tas 27 to 14; and WA 27 to 16.

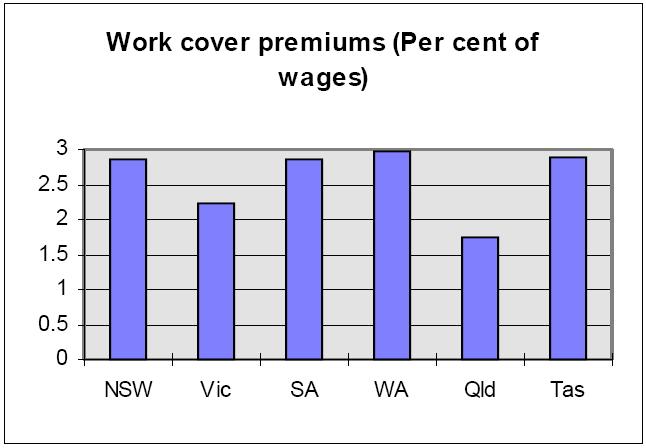

In Victoria, WorkCover went through a period of success in bringing down the average level of insurance premiums and at the same time edging away from insolvency. This process came to a halt and has been reversed over the past few years, partly as a result of the partial restoration of common law rights. Victoria's premium rates remain somewhat below the average as can be seen in the following chart

One difference that would tend to inflate the Victorian achievements is the 10 day "excess" required of employers in paying injured workers, a level that compares to 5 days or less in other states and is not present at all in some overseas jurisdictions. This said, in a comparative analysis, the Upjohn Institute (2) places Victorian outcomes on a par with Michigan, widely regarded as the world's most successful private scheme.

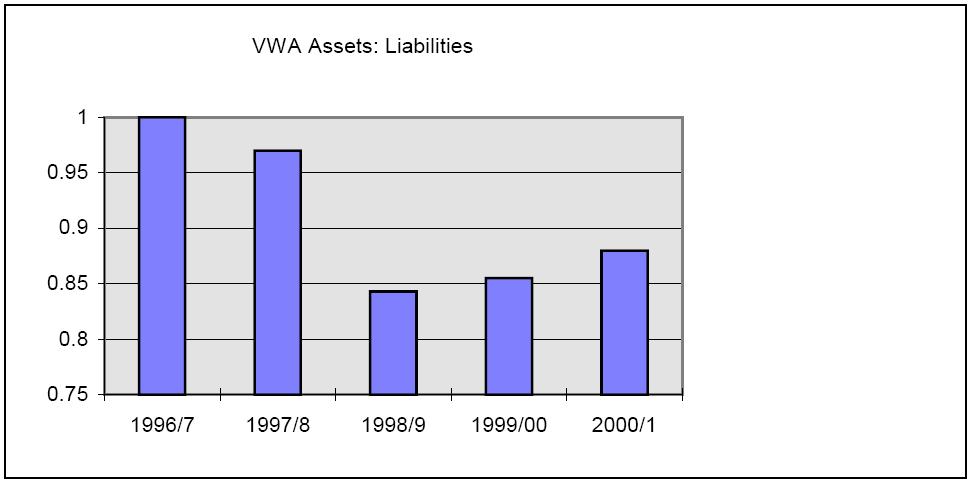

Ominously however, the system has shifted back to insolvency with assets covering less than 90 per cent of liabilities. Moreover, this result is in spite of a very advantageous foreign exchange book stemming from the agency's decision not to hedge its considerable overseas holdings, a strategy which last year allowed it to earn a 6.8% return on investment. Of course, this strategy could have the opposite impact in future.

A FREE MARKET FOR WORKPLACE INSURANCE?

A free market for workplace insurance would leave it to the employer to determine what insurance he should prudently take out and employees would assess this against the general liquidity of the employer and their own risk/reward trade-off.

The fact that people do react rationally to different levels of workplace risk is seen in a number of studies. Viscusi and O'Connor published a piece in the American Economic review in 1984 where some workers were told they would be working with harmless sodium bicarbonate and others were told they would be working with TNT, the latter demanded $3,000-$5,000 a year compensation. Other work has examined payment by job adjusting for skill levels and other factors and derived the premium workers require for different levels of risk. This can be most trenchantly seen in outrider cases: in the American West, the best paid job was the wagon driver who transported nitroglycerine to mine sites.

There have been two features regarding the on-going developments in the common law with respect to worker insurance for harm incurred in the workplace. The first of these has been the virtual disappearance of any liability of the worker herself. This has largely been the result of common law interpretations over the past 50 years. Thus, Courts have found against employers, even in situations where the worker has been injured after an unauthorised attempt to repair a machine and when this involved unscrewing safety barriers.

The second is the inconsistency of a common law system in cases involving worker disability with high levels of efficiency or productivity. Traditionally the common law involved prominent people passing judgement on an issue of dispute. The essence was to arrive at the decision quickly so that commerce could continue. Gradually, as the sovereign took control of the courts, the system became ponderous and ceased to have as much merit for many disputes. This is especially disadvantageous for handling claims involving injured workers, since the incapacitated worker has an incentive to remain injured until there has been a judgement to maximise the payout. This not only rewards malingering but also harms worker health as all studies demonstrate that the faster workers return to work, even with re-arranged duties, the faster the recovery. Indeed, long periods of injury time-off tends to create a psychosis of injury to the detriment of the injured worker in general.

If we go back far enough we can find the system of worker-employer or master-servant relationship that was much different from that which emerged in the industrial economy. Noblesse oblige meant that an employer or a landlord assumed responsibility for an employee who had been harmed in the course of his work, even if the harm was due to the employee's own incompetence. Of course the system did not always work.

Sometime with the onset of the factory system these traditional relationships broke down and employer ceased being seen to be automatically liable for a damaged worker's welfare. The workers' insurance system developed in a way that Peter Huber in addressed in his book "Liability, the Legal Revolution and its Consequences". (3) As Huber puts it the system has shifted from one where contracts held sway and people could choose where they worked on the basis of the work's remuneration, its working conditions location and safety. In Huber's view, "Not long ago, workplace safety was something to be decided between employer and employee often through collective bargaining ….. while compensation for accidents was determined by state compensation laws". Unravelling this ability to contract and substituting court or government imposed conditions has been a major feature of liability law.

Indeed, in 1905 the US Supreme Court rejected a law (enacted on safety grounds) that restricted bakery employees to a 10 hour day. The Supreme Court did so on the grounds that the bakery workers were fully "able to assert their rights and care for themselves without the arm of the State interfering with their independence of judgement and of action". And in overturning the law on bakery workers the Court extended that view to a whole host of other worker–carpenters, printers, and the like (as well as law clerks).

That freedom to contract started breaking down early in the twentieth century and it is difficult to see it being reinstated this century. It is, moreover, unlikely that it can be skirted by a stratagem of using contractors. Contractors would probably have their contracts re-visited under liability law and, as they have with others, the Courts would tear up the contracts and thereby deny the parties the ability to contract.

In redefining liabilities Courts are doubtless reflecting sympathy for the injured, often on the basis that a major firm can afford to offer compensation. However, such redefinitions create new systems of incentives and change behaviour. In the case of product liability generally, applying strict (or, in effect, total) liability to the seller, requires the firm to engineer into the product or service much higher levels of safety. The costs of this are incorporated into the product and paid for by the consumer, and in some cases the demand is severely curtailed as a result. Huber points to many products and services where what he calls the "liability tax" is higher than the naked service or product price.

In the case of employment, the costs of tilting the insurance/liability law towards the employer are eventually born by employees, or rather the employees other than those who are of a reckless disposition. The increased costs are factored into wage and employment levels, in both cases reducing them from the levels that would otherwise prevail.

IMPROVING THE SYSTEM

OPERATIONS OF WORKCOVER

Accident insurance in the context of employment relationships has considerable scope for affecting outcomes (such as workplace safety) when parties are constrained in their ability to reassign or reallocate risks.

There are several hundred classifications that are presently in place. These offer a major target for "gaming" the system by either the firms or by agents anxious to win their business. Prices are open to such flexibility by the insured firm by:

- segmenting its workforce so that high premiums are restricted to only the most direct operators with others classified into low risk white collar work.

- definition hopping where work takes in several different activities.

- reclassifying the activity, for example sheep farming, which WorkCover gives a rating 7 into combined meat and sheep (rating 5.78).

The actuarial approach to specifying ratings is necessarily static since it takes no account of the ability of incentives to improve outcomes. The presence of explicit "price signals" (together in concert with the prevailing penalties and liability rules) creates the appropriate incentives for all actors (employers and employees alike) whose actions or inactions may affect the likelihood or severity of workplace accidents. All this said, the biggest employers are already experience rated (and automatically so if they are self-insurers). For any Victorian employer with a payroll of over $1 million some experience rating affect is included in the overall rate set, though this is quite small for payrolls of smaller companies.

In Victoria, the VWA is the monopoly insurer but uses agents to administer the scheme and act as the interface with the insureds. In March 2000, VWA announced an opening for new firms to undertake this essentially sub-contractual work. None have yet been appointed as the tender process remains underway. A tender process involves the VWA engaging in a "beauty contest" form of selectivity. Yet determining appropriate levels of efficiency is difficult and it is generally preferable to have simple open access to an activity (providing adequate fiduciary arrangements are in place) and leave it for suppliers to fight for the market. In this respect, compared to the ten agents licensed in Victoria, there are hundreds in the low cost beacon jurisdiction of Michigan. (4) A preferred approach to that of VWA is to have open access of insurers subject only to normal assurances being required of funding adequacy etc.

SELF INSURANCE

A change brought in by Victoria's 1998 legislative amendments facilitated selfinsurance. This removed a fixed capital threshold and minimum employee requirements as preconditions of eligibility to apply for and maintain approval as a self-insurer. Not only may employers now opt to self-insure, the Second Reading Speech also envisaged the possibility of employers engaging suitably qualified external parties to undertake claims management powers and functions on their behalf (ie. third-party administrators). However, employers remain accountable under the legislation for their injury and disease prevention, claims management and return-towork performance and for underwriting their own risks.

Self-insurance enables an organisation to manage its own claims and have full responsibility for meeting its claims liability. From an economic standpoint, self insurance leads to a full internalisation of an employer's cost in regards to claims management and return to work of the injured worker and, as a consequence, it creates sharper incentives for the employer to manage workplace risks and safety.

Most schemes attempt to replicate this, in part by giving discounts based on performance. But in general, this is only practicable for the largest firms and is less than satisfactory even for them.

In contrast to individual firms' rating systems, under self insurance, cost savings derived from reducing liabilities are retained wholly by the employer rather than shared. Many firms self insure because want to control their own performance and benefits/costs. In addition, self insurance avoids the automatic cross subsidy that occurs with any insurance scheme and which is added to in most state based systems by capping the rates of the most injury prevalent industries and by implicitly using larger firms to subsidize the smaller. In most US jurisdictions where insurance is open to competitive provision some 40-50% of employees are covered by employer self insurer schemes.

In recognition of the costs (and financial hardship) that would be imposed upon injured workers should a self insured employer fail, the jurisdiction requires employers to satisfy a stringent set of prudential and financial conditions before they are approved as self insurers. Basically employers have to demonstrate that they have the financial capability to meet their current and future claims liabilities, including those arising at common law or in respect of past and future work injuries.

There are currently 31 employers approved as self insurers in Victoria, having been increased from 23 a couple of years ago. Around 12 per cent of Victorian employees are under these schemes.

The latent demand for self-insurance is at least as great as the number of eligible employers (thought to be over 300 (5) even prior to the recent liberalisation, although the requirement that self-insurers must be "above average" in claims safety, performance etc. presumably halves the potential number!). The fact that only 31 employers have sought (and received) self insurer status raises a question as to the factors that would transform the latent demand into realised demand. These factors may be primarily organisational in nature.

According to information from overseas, firms that self-insure have injury rates that are 30% below expectations. (6) Similarly, self-selected groups of firms are cited as bringing cost savings in New York of some 5% in addition to the premium concessions they are given. These self-insurers also tend to spend more on accident prevention and rehabilitation. Firms that self-insure avoid the policing costs of ensuring people are appropriately categorized. They also (should, at least partly), avoid the bundled costs of the poor performing firms within their categorization and the incidental costs of promotion, advertising campaigns etc. In fact, in Victoria they are obliged to contribute to these common costs. Some of these clearly involve common goods-type benefits.

Increased numbers of self-insurers would lift the economy-wide performance. It would do so partly because of the effects on the firms taking such activity and partly because it would transfer costs back to other firms that should rightfully bear them and in doing so encourage those other firms to look more carefully at the cost/benefits of changed work practices.

Divorcing a firm's performance from an aggregate industry average is at the heart of using the premium and associated pricing system to drive lower costs. Self selection of smaller firms into quality groupings is the equivalent of the self-insurance facility presently available to larger firms. As with self-insurance it would be expected to bring a better alignment of fees to risks and offer better incentives to take the necessary action to reduce risks. In short, it would reduce the level of injury.

DEREGULATION

Deregulation involves jurisdictions no longer setting rates nor oversighting those set by insureres. One of the best publicised cases of deregulation was Michigan, where a 32 per cent decline in the average rate was seen 1978-1984. (7) Barkume and Ruser (8), in a more comprehensive study of 50 states, show a major reduction in premiums and days away from work when competition was introduced. They estimate a fall in days away from work of about 9.5% and a 13% reduction in premiums.

Normally deregulation is accompanied by a fall-back rate for those who would otherwise be uninsured. A relatively low fall-back rate can, of course, frustrate the deregulation by leaving no head-room for competition.

Allowing agents and combinations of firms to gain financially where such gain is warranted can be a vital part of the cost/injury reduction strategy. It can bring a better alignment of costs and premiums thereby reducing the potential for moral hazard. The potential gains from an approach that uses the agents as catalysts and mechanisms for achieving those gains will be fully investigated.

Establishing strong relationships with and seeking a measure of control over the medical advisers to injured workers is an essential element in complimenting the very successful media campaign to encourage injured workers to return to their employment at an early stage. Nonetheless, a major cost to the system is the "long tail" of injured people who remain off work for many months. In many cases, this is a symptom of wider dissatisfaction of the employer with the employee or vice-versa. Means of identifying these underlying causes and establishing incentives or penalties to the symptoms are an integral part of the premium model.

CONCLUDING COMMENTS

Compulsory workplace insurance is here to stay. While a perfect centralised system of compulsory insurance is feasible, experience and data demonstrates we won't get this. Deregulation of worker insurance, while maintaining it as a compulsory system is probably the most practicable route to reform. It would likely bring advantages of:

- savings and lower costs that have already been demonstrated overseas

- premiums more closely aligned to risks and a better discovery process of the true risk as a result of competition for business rather than a monolithic premium structure

- removing new contingent liabilities from the taxpayer (although existing claims have a long tail)

- removong an area of potential political patronage and claims that the government agency is being used to pursue unrelated agendas.

Particularly in view of the long tail of claims and the sometimes lengthy period before an injury manifests itself, moving to a more deregulated more privatised system would also have to be considered in the light of transition costs that might be involved.

Any system would be mightily assisted, in terms of costs to employers, and therefore jobs since these costs must be passed on, if Courts started to shift from the strict liability ideology that has increasingly prevailed. There needs to be a balance of responsibilities between the worker and the employee and this has probably tilted too far away from the employee. As a result costs are driven up and we have a case of the reckless worker penalising the jobs and the income levels of the great bulk of employees and potential employees.

ENDNOTES

1. NOHSC reports, "The WRFS 2 21 provides the only reliable, comprehensive national data on workrelated fatal injury. No information on work-related disease is provided by the study. Number of deaths each year: 450. Rate of deaths: 5.5 per 100,000 working persons per year. The NDS is the only current source of on-going information on work-related deaths, but it probably significantly underestimates the overall level of work-related death. Number of deaths each year: 406 (260 from "injury" and 146 due to "disease") Rate of deaths: 5.8 per 100,000 working persons per year."

2. Hunt, H Allan Three Systems of Workers' Compensation, Employment Research B Fall 1998

3. Basic Books, New York 1988

4. Hunt, H.A., and Klein, R.w., Workers' Compensation Insurance in North America: Lessons for Victoria? Upjohn Institute Technical Report No 96-010, November 1996

5. Department of Treasury, Review of workplace accident compensation legislation, January 1998.

6. One US State study guardedly reported that self-insured employers achieved a much faster return to work. For those cases involving more than 30 days off self insured averaged only about 59 days, while the other groups averaged 97-115 days. In the case of those off work for less than 30 days, self insured were only 0.3-1.5 days less than the other groups. Worker's Compensation System Performance Audit Report 98-9, State of Washington Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee, December 11, 1998.

7. Allen H. Hunt, Alan B. Krueger, & John F. Burton, Jr., The Impact of Open Competition in Michigan on Employers' Costs of Workers' Compensation, in Workers' Compensation Insurance Pricing 109 (David Appel & Phillip S. Borda eds. 1998).

8. Barkume A.J., and Ruser J.W., Deregulating property-casualty insurance pricing: the case of workers' compensation, Journal of Law and Economics, vol. XLIV, (April 2001)

No comments:

Post a Comment