Australian farmers need the right to export.

The government must immediately eliminate the single desk.

THE WHEAT INDUSTRY

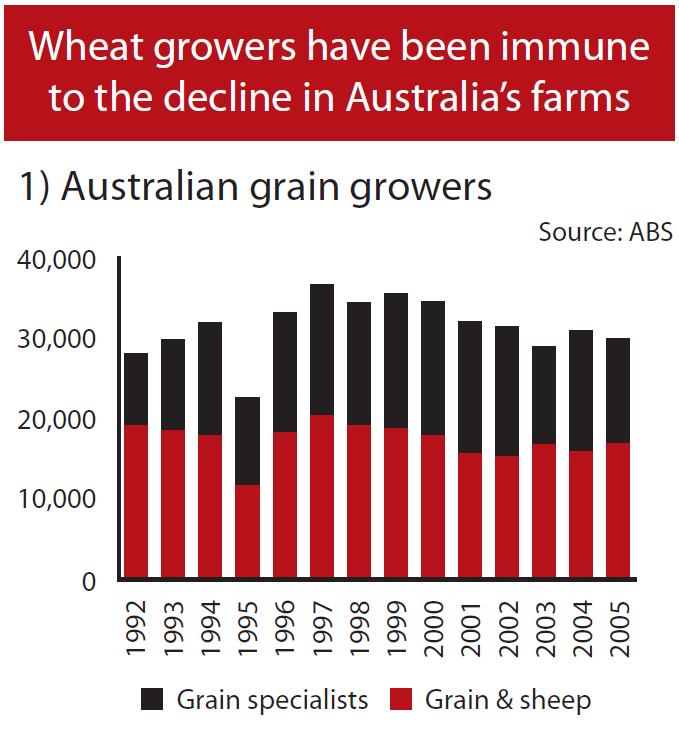

Australia has about 30,000 wheat growers comprising of 12,700 cropping specialists and the balance in combined grain and sheep enterprises. Despite the stability of grain grower numbers, productivity improvements have continued to drive increases in crop size. The Productivity Commission found that over the past three decades the cropping industry has shown the largest productivity gains (3.3 per cent a year) within agriculture. Productivity gains in cropping have also outstripped the economy wide productivity increases over the past thirty years.

Wheat is the dominant winter crop grown in Australia, on average 13.4 million hectares are planted of wheat compared to 4.5 million hectares for barley and 1.3 million hectares for canola. On average 75 per cent of the Australian wheat crop is exported.

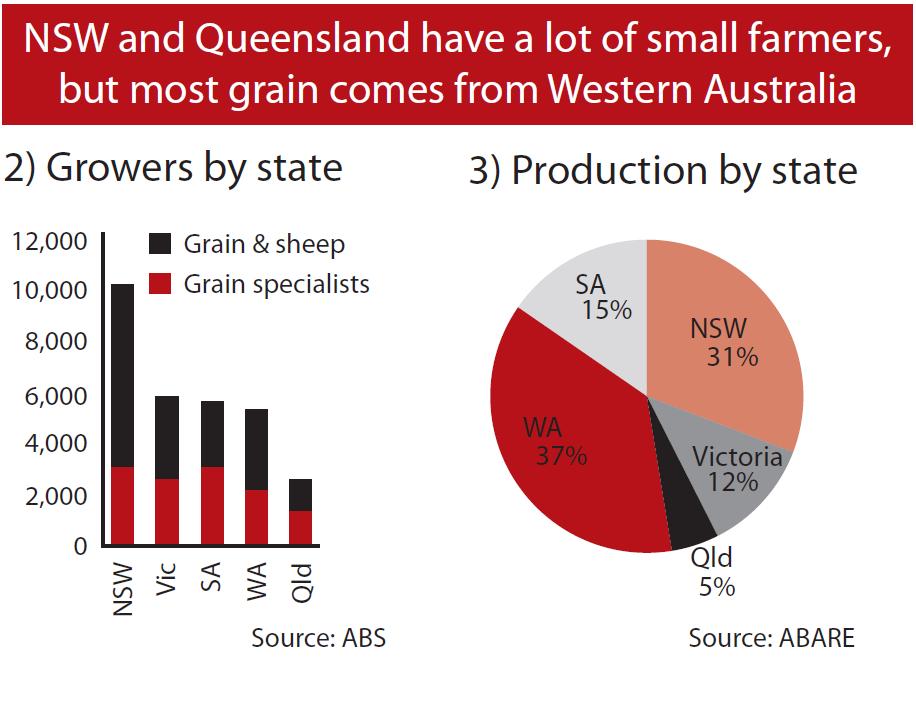

Western Australia is the largest wheat producing state despite having only 18 per cent of wheat growers. The WA industry has undergone the largest degree of specialisation and concentration in recent years so that the average wheat growing farm in WA is now 1½ times larger than in NSW and 2½ times larger than in Victoria.

The wheat industry is becoming increasingly concentrated and specialised. Over the past 15 years the proportion of total wheat receipts received by large farms (those over $400,000 in production value) has doubled from 41 per cent to 83 per cent, even though large wheat growers only make up 38 per cent of total farmers. Even this may understate the true level of concentration with the Productivity Commission estimating only "10 percent of Australian farm businesses now produce over 50 per cent of output". At the other end of the scale, small-scale wheat growers, who are particularly concentrated in NSW and Queensland, now only produce four percent of the wheat crop despite comprising one third of all wheat growers.

EXPORTING WHEAT

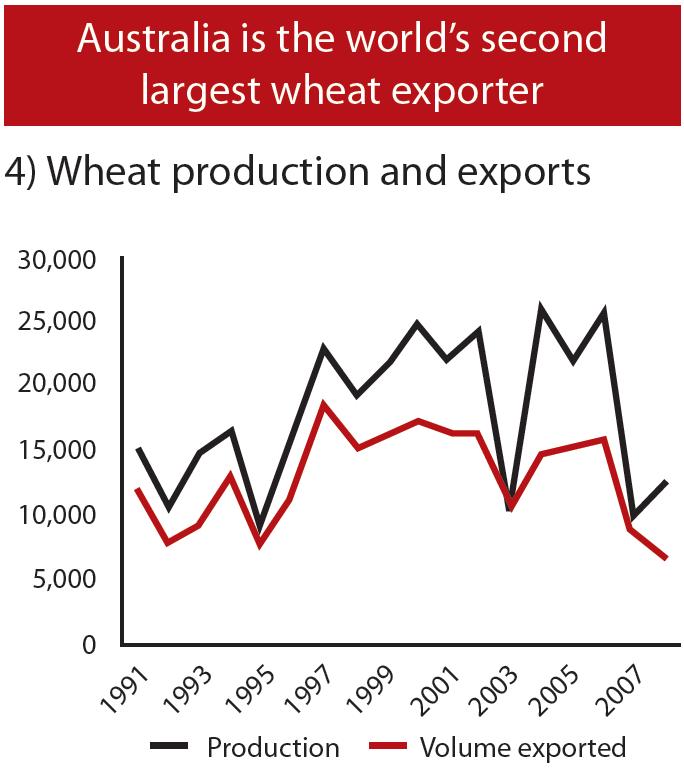

Wheat continues to be an important export for Australia. While the two most recent seasons have been seriously affected by drought the future for Australian wheat is very attractive with global prices higher than they have been for many years and planned plantings well up on recent years. If the drought has indeed broken, returns from cropping can be expected to reach record levels over the next few years.

Australia is the world's second largest wheat exporter. Major markets include China, Iraq, Indonesia, Japan, Korea and Egypt. In the last non-drought year, 2004-05, Australian wheat exports earned $3.591 billion.

Source: Historical ABS, 2008 ABARE

Access Economics estimates 90-95 per cent of the Western Australian wheat crop is exported each year compared to a much higher domestic consumption of eastern seaboard wheat. Because of the lack of domestic demand in WA, at harvest growers in that state have to date been captive to the single desk price unlike eastern states wheat growers who can choose to sell to the national pool or to a wide variety of domestic buyers.

THE GOVERNMENT'S WHEAT EXPORT POLICY HAS BEEN STEADILY DEREGULATED OVER THE LAST FEW DECADES -- BUT NOT ENOUGH

| - the creation of the single desk giving the Australian Wheat Board powers to aquire all wheat produced GONE

- a home consumption price for wheat GONE

- guaranteed prices to growers and a stablisation fund GONE

- compulsary pooling and coordinated marketing of wheat and coarse grains GONE

- entire supply chain government owned and operated GONE

- AWB holds right to market all wheat overseas GONE

|

| - domestic feed wheat deregulated (1984)

- domestic milling wheat deregulated (1989)

- non-bulk export veto by Australian Wheat Board abolished.

- elimination of guaranteed minimum prices to growers.

- AWB control passes to grower elected representatives.

- AWB financed by two per cent levy on earnings from sales to the pool.

|

| - Australian Wheat Board was corporatised and privatised. AWB listed on the ASX on 22 August 2001.

- federal government decreased and eventually eliminated its underwriting of the national wheat crop.

- bulk handlers (the old state Grain Elevator Boards) were corporatised, privatised and in some cases listed. Considerable consolidation ensued.

- coarse grains deregulated in all states except South Australian which deregulated its barley market in 2006.

- oilseeds and other crops deregulated in both the domestic and export markets.

|

| - bulk export veto temporarily transferred from AWB to the Minister for Agriculture until 30 June 2008.

- deregulation of container and bag exports with the result of bagged wheat exports jumping seven-fold compared to regulation.

- without legislative change AWB will regain the single desk bulk export monopoly from 1 July 2008.

|

WHAT ARE THE ELEMENTS OF THE SINGLE DESK?

Power to export wheat held by the Wheat Export Authority

It is an offence to export wheat without permission of the WEA except for AWB(I) which doesn't need a permit. This provision of the Wheat Marketing Act, along with a veto which effectively stops the WEA from issuing bulk permits is the core of the single desk.

Bulk export veto

The veto allows AWB to stop the WEA from approving any other bulk wheat exports except by AWB(I). Until 2007 the veto was held by AWB when, in light of the Cole Enquiry, it was transferred to the Minister for Agriculture. The veto will revert to AWB(I) on 1 July without legislative change.

Although a few permits for bulk export were issued for this harvest, the vast bulk of the harvest was delivered to AWB for marketing.

Buyer of last resort

The holder of the single desk licence, AWB(I), is required by the Wheat Marketing Act to accept all wheat delivered to it.

It is a common misconception that this wheat receives the average pool price, in fact all wheat is received into the pool into various broad quality bands which receive differing prices and the very low quality wheat accepted under the buyer of last resort provisions is heavily discounted. Typically "buyer of last resort" wheat comprises less than two percent of the total pool.

National pool

The national pool is the mechanism used to implement the single desk.

Under the single desk all export growers are required to deliver their wheat to AWB which runs a national pool for the purpose. As a result all growers of similar quality wheat receive the same price. The grading and pricing is set by AWB and ACIL Tasman found the national pooling system has led to a decrease in the quality of some grades of Australian wheat and an inability to match specialist buyers needs with what Australian growers produce.

The risk to growers from a national pool is that the pool operator gets the hedging wrong and thereby delivers lower returns than would otherwise be available. With no alternative to the pool growers are very reliant on the skill of the pool operator. The national pool has been found to contain significant cross subsidisation of costs, essentially in favour of east coast growers at the expense of WA growers. No analysis of the national pool has concluded grain growers have benefitted from the system. Most analysis has pointed to excessive costs of running the pool while even a report by ITS Global commissioned by AWB found no price premiums achieved.

Despite some commentary to the contrary, the end of a national pool does not mean the end of all pools. For example even with the total deregulation of the Victorian barley market it is estimated some 80 per cent is still delivered into pools in some years. Many growers have only ever delivered their wheat to the national pool and the thought of having to make wheat marketing decisions is causing concern among smaller older farmers. This is clouding some farmer's views on overall wheat marketing reform.

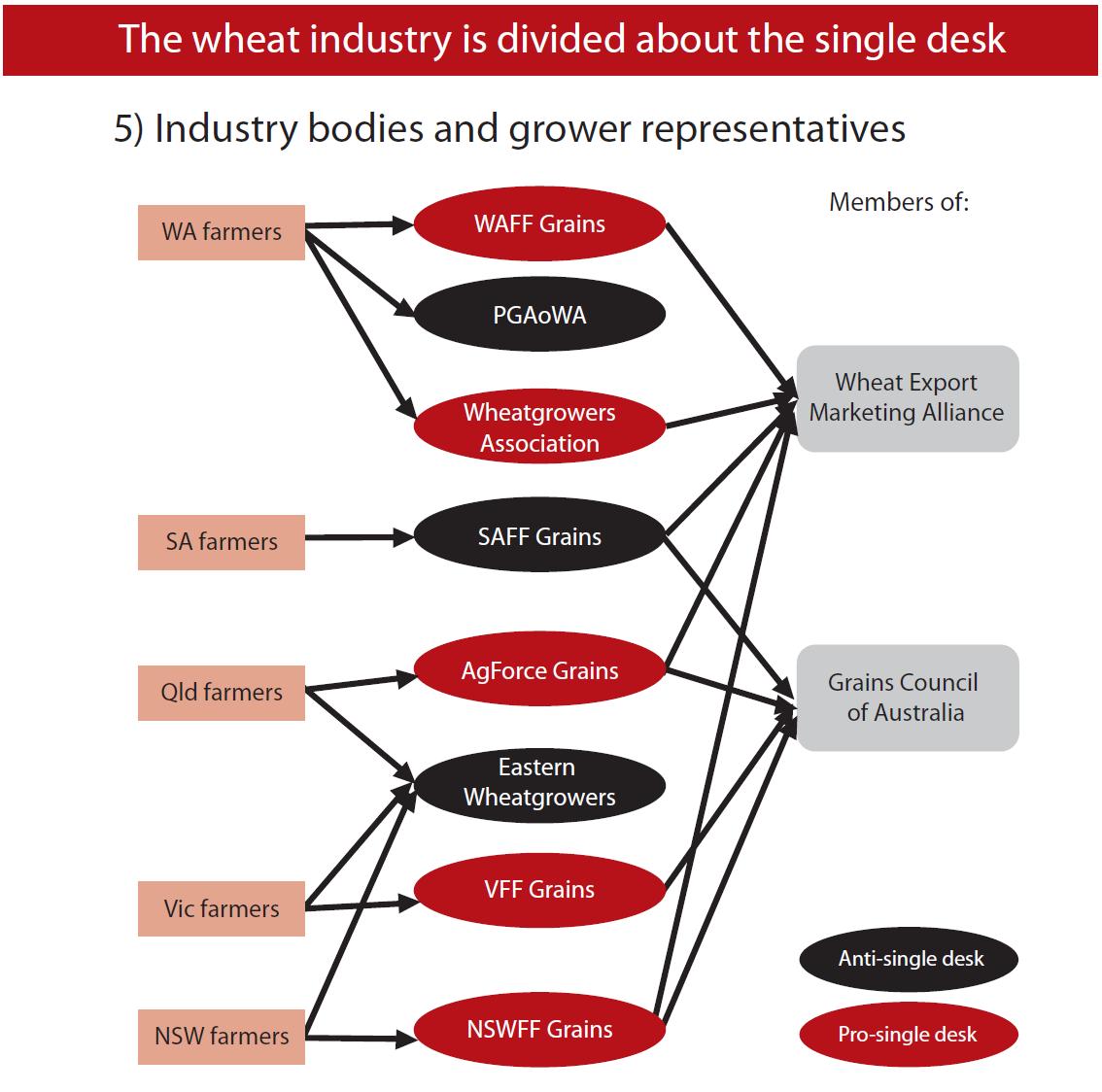

Over the years the representative structure of the grains industry has fragmented. A key cause of this fragmentation has been divisions over the single desk. With the exception of South Australia's Farmer Federation which no longer supports the single desk, the older, larger farmer bodies still advocate retention of a single desk in some form. However every state now has a pro-deregulation group of farmers.

Sources: Western Australian Farmers Federation, media release, 27 Nov 2007; Pastoralists & Graziers Association of Western Australia, media release, 6 Feb 2007; Wheatgrowers Association, media release, 22 May 2007; South Australian Farmers' Federation, media release, 23 May 2007; Agforce Grains, key policies: "AgForce Grains supports the single desk export powers for wheat marketing"; Eastern Wheatgrowers, submission: "The Eastern Wheat Growers is a grower lobby group representing east coast wheat growers who would like to see the Australian export wheat market opened up to competition"; Victorian Farmers' Federation, media release, 18 Dec 2007; New South Wales Farmers Association, media release, 12 Oct 2007.

The national peak body for grains is the Grains Council of Australia (GCA). While nominally pro-single desk, in recent times this body has declined to campaign on the issue, largely because its membership is divided. In 2007 the Wheat Export Marketing Alliance (WEMA) was formed to attempt to become the new farmer controlled holder of the single desk licence. WEMA's fundraising efforts were unsuccessful and with the election of the Rudd Government and its policy of partial deregulation WEMA no longer has a purpose. However it has morphed into an advocacy body for the most virulent single desk supporters.

Furthermore, smaller and semi-retired farmers have had a disproportionate voice in farmer surveys. These are the farmers most likely to be resistant to change. Perhaps a better indication of the true views of farmers can be gleaned from the very poor response by wheat growers to a request for money from WEMA to start a new farmer controlled organisation to hold the single desk licence.

THE WHEAT EXPORT MARKETING BILL AND THE FUTURE OF WHEAT

An exposure draft of the Wheat Export Marketing Bill was released by the federal government on 5 March 2008. The key features of the proposed legislation are a licensing system for exporters and an opening up of bulk grain facilities to competition.

While not the full deregulation found in other grain markets, Labor's policy is a significant step towards full liberalisation of wheat export marketing. Potential exporters will apply for a license to export from Wheat Exports Australia (WEA). There will be no single bulk exporter. As a result there will be no national pool run by AWB because growers will have greater choice to use regional pools and other grain marketing options. Also there will be no legislated buyer of last resort since all wheat will be sold at a market price. This new legislation will therefore deliver the higher grain prices to growers forecast in many studies over many years.

The most robust and transparent licensing system is one that operates from a publicly available set of criteria. Appropriate criteria include financial probity and capacity to finance wheat exporting, export experience of agricultural bulk commodities and high standards of corporate governance. The proposed legislation requires the WEA to have regard to these sorts of criteria but does not require the WEA to publish specific criteria. This is a deficiency in the draft legislation and should be rectified so both farmers and exporters are clear what accreditation is based on, especially in relation to capacity to finance wheat exporting.

Despite these shortcomings, the draft legislation is a positive development. In particular the opening up of the entire supply chain to competition will be most likely to offer farmers the greatest opportunity to benefit from high global wheat prices.

The single desk is outdated and anti-competition.

The federal government needs to eliminate it.