Submission to the Taskforce on Reducing

the Regulatory Burden on Business

1. THE REGULATORY MINDSET

Individuals should be free to truck, trade and barter. Over two hundred years ago, these insights founded on the bedrock of individual property rights and the "liberty" of the individual from arbitrary actions of government were assessed as the causes of the wealth of nations. We have emerged from an era, which ebbed and flowed but reached a crescendo some three decades ago, during which the merits of these words were downgraded. The impact of socialist thinking penetrated and sometimes suffused government decision taking and led many to believe that "experts" would offer better advice as to how the economy should work than the various individuals that comprise it.

While such thinking is no longer prevalent, as the recent Productivity Commission (PC) report on Energy Efficiency demonstrates, it still percolates much of government decision making. It has, in more recent times, been surpassed in its ubiquity by the more corrosive and less refutable claim about "externalities". Externalities as unpriced values concomitant with a transaction offer ready justification for actions of all kinds.

Almost simultaneously with the current federal government review of Red Tape and notwithstanding the PC's advice in its Energy Efficiency Report, the federal Government has unabashedly announced the Energy Efficiencies Opportunities Bill. The aim of this bill is to introduce a regulatory requirement on business aimed at energy saving that has already been found to be of little worth by the Productivity Commission. Its Regulatory Impact Statement (RIS) argues that business firms can profit by taking additional energy saving measures and should be made to do so. The Business Council considers it most unlikely that a government agency without the day to day operational responsibility of managing businesses and without the motivation that comes from the private sector pursuit of profits can know better what is in firms' interests than their management.

While paying lip service to the case against introducing new regulations, in a time honoured procedure long used by those looking to increase regulation the government argues that this particular case is unique. It suggests there is an energy efficiency gap caused by the following:

- Market failures, including imperfect information, split incentives and externalities;

- Organisational failure and behavioural norms; and

- Other reasons, including hidden costs.

The hypocrisy that such statements encapsulate is easily demonstrated by examining the spurious empirical data within the RIS and the fact that its arguments have been rehearsed many times over in the past by those looking to increase regulation.

Hence, notwithstanding a greater awareness of the need to curtail regulation to allow faster growth, new regulations of highly doubtful merit continue to be introduced. Often this is because of governments' reacting to immediate pressures and either neglecting or not properly undertaking the sober analysis that should properly inform them of the merits of regulatory action.

This said, we hasten to add that Australia is by no means as over-regulated as some other prominent economies. Indeed, according to World Bank data the costs of doing business in Australia are relatively low. (1) The following table was developed using seven criteria (Starting a business; hiring and firing workers; obtaining credit; registering property; enforcing contracts; protecting investors; closing a business).

Even so, Australia does not fare well on several of the criteria, in particular protecting investors and registering property. Moreover, we are in a highly competitive world environment. The sclerotic nature of many European economies which fail to make the above top 20 list is in contrast to those like the UK, Ireland and the Netherlands that do. There is now a far greater realisation of the costs that over-government and over-taxation can bring even to economies that not so long ago were regarded as engine rooms of world growth. If for no other reason, retaining our competitiveness makes it vital that Australian Governments do all they can to minimise regulatory excessive costs.

Top 20 Countries on the Ease of Doing Business

| 1 | New Zealand |

| 2 | United States |

| 3 | Singapore |

| 4 | Hong Kong, China |

| 5 | Australia |

| 6 | Norway |

| 7 | United Kingdom |

| 8 | Canada |

| 9 | Sweden |

| 10 | Japan |

| 11 | Switzerland |

| 12 | Denmark |

| 13 | Netherlands |

| 14 | Finland |

| 15 | Ireland |

| 16 | Belgium |

| 17 | Lithuania |

| 18 | Slovakia |

| 19 | Botswana |

| 20 | Thailand |

Note: The ease of doing business measure is a simple average of the country's

ranking in each of the 7 areas of of business regulation and property rights

protection measured in Doing Business in 2005.

Source: Doing Business database

2. TRENDS IN REGULATORY GROWTH

The most obvious point to make about the level of regulation in Australia is its extraordinary growth over time. Parliaments seemingly have an almost insatiable desire to push through ever greater amounts of legislation and regulation with every passing year. In the years from 1991 to 2004, the Commonwealth Government produced approximately as many pages of legislation as had been passed over the previous nine decades since Federation.

Not only have the total pages of legislation continued to grow, but the complexity and average lengths of Acts passed also continued to increase. Similarly, all of the state governments show long-term upward trends in the amount of legislation and regulations passed. The concern is not just with the volume of new legislation, but cumulative effect of the existing body of legislation.

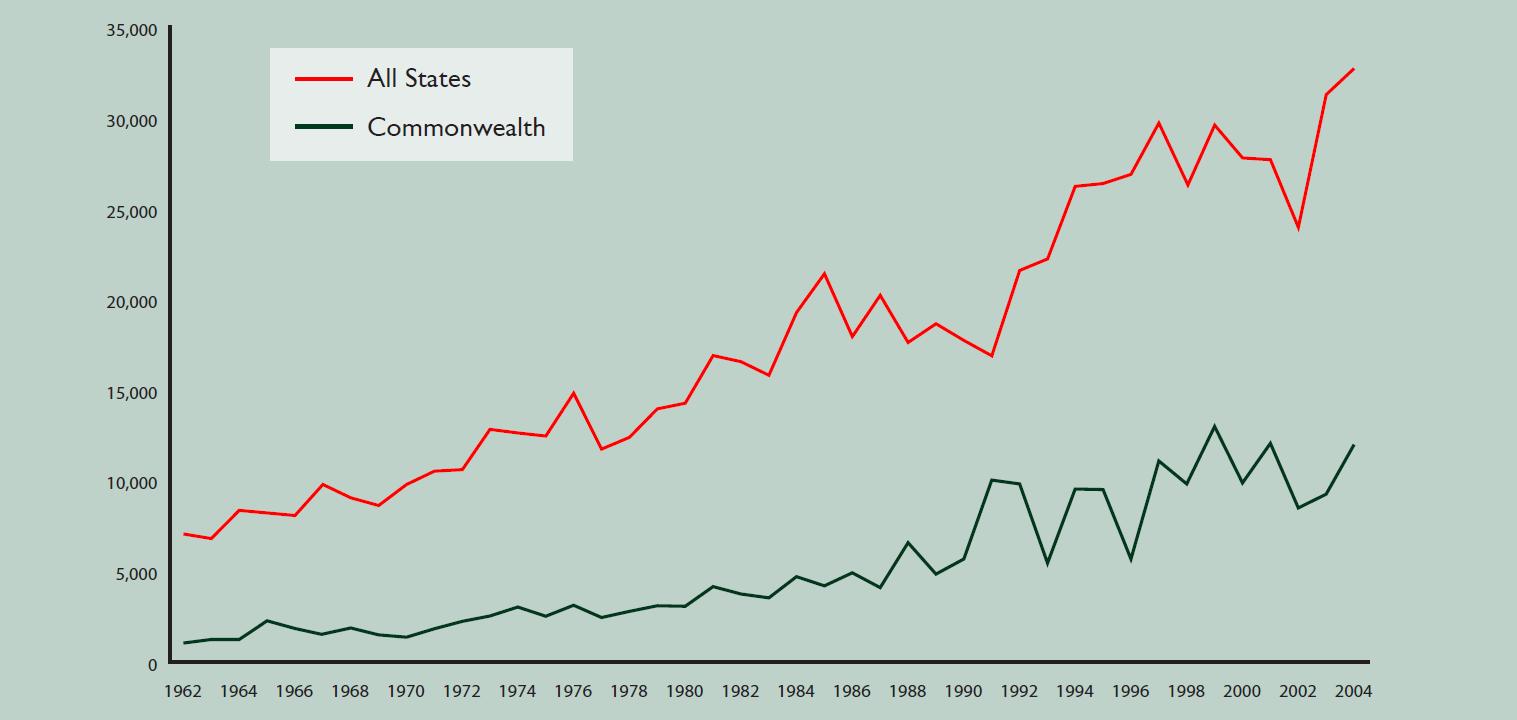

While the Commonwealth Government has shown a strong propensity to increase the stock of regulation over time, a bigger problem lies with the States. As shown in the graph below, while the volume of new legislation and regulations passed by the Commonwealth Government each year measured in terms of pages has increased dramatically, the states taken together have been far worse. The volume of new legislation and regulations enacted by the States is both larger and has increased more sharply over time than has the Commonwealth's. In 2003-04, the States enacted nearly three time the volume legislation and regulation of the Commonwealth. What is more, the graph understates the total amount of legislation generated at the state and territory level as it does not include the ACT, the Northern Territory, or subordinate legislation produced by South Australia or Western Australia. It also does not include the volume of regulation passed by local governments.

Pages of Legislation passed by Commonwealth Parliament

| Total Pages | Average per Act |

| 1900s | 1,072 | 6 |

| 1910s | 1,195 | 3 |

| 1920s | 1,515 | 3 |

| 1930s | 2,530 | 3 |

| 1940s | 2,795 | 4 |

| 1950s | 5,274 | 6 |

| 1960s | 7,544 | 6 |

| 1970s | 14,674 | 9 |

| 1980s | 29,299 | 17 |

| 1990s | 54,573 | 31 |

| 2000-04 | 28,373 | 36 |

Source: Acts of the Parliament

Pages of Legislation and Regulations Passed: Commonwealth vs States, 1962-2004 Source: Annual publications of statutues and subordinate legislation. Pages of legislation and regulations for some years in some jurisdictions based on estimates. Does not include legislation or regulations from the Northern Territory or the Australian Capital Territory, and does not include regulations for South Australia or Western Australia.

Source: Annual publications of statutues and subordinate legislation. Pages of legislation and regulations for some years in some jurisdictions based on estimates. Does not include legislation or regulations from the Northern Territory or the Australian Capital Territory, and does not include regulations for South Australia or Western Australia.

It should also be remembered when looking at this graph that this represents only the flow of new legislation every year. What individuals and businesses have to daily comply with however is the actual stock of legislation already in existence and constantly been made worse by the cumulative effect of new legislation that is continually being added on top of it.

It is highly questionable whether there is any serious need for this continual growth in regulation, and begs the question as to why it continues to increase. To some extent it may simply reflect the fact that as nations becoming increasingly wealthy, they also become more risk-averse and are more likely to demand regulation to minimise the risks that were once taken and being part and parcel of daily life. However, as British Prime Minister Tony Blair has pointed out, it is neither possible nor even necessarily desirable to eliminate risk beyond a certain point. There is an urgent need for Australian governments at all levels to make this point to their own constituents, and point out that demands for risk-minimisation can be very damaging and counterproductive when taken to the level that is now becoming increasingly common.

Perhaps even more importantly however, there is also a need for governments to look at the institutional drivers of regulation and whether the incentives facing regulators are at present aligned with what is in the interests of the broader public. Much legislation is now undoubtedly being driven by bureaucratic empire building or alternatively by risk adversity among policy-makers seeking to insulate themselves against blame for future potential problems by engaging in legislative overkill before anything has actually happened. It is important that all levels of government, but particularly at the state level, create more coherent and sensible processes for the introduction of new legislation to ensure consistency, transparency and that the benefits will outweigh the costs.

Issues of regulation concern all levels of government. We assign the different matters into one of three streams:

- Commonwealth regulations

- Commonwealth/State collaborative regulations

- State (and local government) regulations

Following are some examples of regulation in the three above areas. These examples are not exhaustive, but take the form of case-studies that are illustrative of the problematic nature of much of the regulation in place in Australia today.

3. COMMONWEALTH REGULATIONS

3.1. ANTI-DUMPING ACTION

One of the few non tariff barriers being used in to combat imports at the present time is the anti-dumping regime. Anti-dumping actions can be brought about when an overseas supplier provides goods to Australia at lower prices than in its home market. Such "dumping" is only possible where the supplier's home market is protected by tariffs or other barriers.

In the absence of protection, the supplier's cheap exports will be re-imported. In fact, in today's internet age, they would probably never leave the home country thus depriving the supplier of a base to export at below-cost prices.

But why should we be concerned that a supplier is providing us product too cheaply? Traditionally the case agaisnt dumping was that the supplier was trying to knock out domestic competition after which a price rise would be introduced and the supplier would recoup the lost profits incurred during the price war. Based on the literature surrounding pricing, DeLorenzo (2) among others has shown the concept to have no credible examples in support of it and recent Nobel Prize winner Vernon Smith demonstrated that the theoretical basis for it was unsound.

Others support the ability to take such action on the basis that low priced opportunity or distress sales by a foreign supplier priced at marginal cost could damage a domestic business perhaps irreparably. However this concern is present with domestic on domestic competition as well and could be used to justify prior scrutiny of all prices. It is most certainly true that a business in the process of offloading stock, perhaps to avoid bankrputcy or minimise losses, can seriously damage competitors even highly stable businesses. However, this is just the sort of action we see in petrol stations' price duels. It is also the sort of actions that Australia's agricultural exporters constantly engage in when our exporters seek to get the best price for their produce across dozens of markets, recognising that the ebb and flow of global competition will move prices up and down. All this is part of the normal business environment and to attempt to prevent it leads to far more serious adverse consequences of a governmentt interfering with the market processes.

Even though anti-dumping proposals need to progress through a bureaucratic mill that involves painstaking checks of prices as well as evidence that the imports are actually causing damage to the profits of the local firm, they offer opportunities for a local supplier to raise a competitor's costs of doing business.

The availability of an anti-dumping challenge to imports can seriously distort a business's internet based global sourcing strategy. Even the threat of action can introduce a risk both to the buyer and the seller.

Australia is among the world's most aggressive users of anti-dumping actions. Economies like Japan, Taiwan and Israel take hardly any anti-dumping actions. In the interests of a more competitive Australia, we should abolish the regulatory arrangements that facilitate the trade intervention on dumping grounds.

3.2. AIR TRAVEL

At present, instead of allowing any airline carrier to enter the Australian market to provide flight services, the Australian government barters for reciprocal access elsewhere as part of the international bilateral system of air services arrangements between countries. This arrangement imposes heavy costs on Australian consumers.

Restrictions prevent foreign airlines from flying as often as they would like from Australian cities to overseas destinations, or from flying domestic routes. This undermines competition and hence has the effect of raising prices above where they would otherwise be in a competitive market. The outcome is harmful not only of consumers, but also of other downstream industries largely reliant on air travel (such as tourism for example -- an important and growing sector of the Australian economy).

The Australian government should abolish restrictions on cabotage and other uncompetitive regulations, and adopt a genuinely open skies policy for air travel. Sometimes the argument is put that deregulation of this kind would undermine Qantas, which needs protecting as the national airline. There is no reason why Qantas could not continue to thrive and prosper under such a regime however, but furthermore, policy should be dictated by what is going to be good for the consumer rather than spurious arguments related more to ill-conceived notions of nationalism than economic good sense.

More competition in air travel would result in cheaper tickets, greater capacity, and greater choice, as well as improve the well-being of other industries reliant on cheap and effective air travel. Thus, those restrictions undermining greater competition should be abolished.

3.3. WHEAT MARKETING

The Australian Wheat Board (AWB) has been left with a monopoly over wheat exports allegedly because only then could scale economies be reached. In point of fact, the AWB's monopoly (much abused in the Iraq oil for food scandal) only serves to constrain the variety of wheat offerings by leaving those growers seeking to serve specialist markets with inadequate recompense for doing so.

Another argument sometimes put forward in favour of the AWB's export monopoly is the notion that selling through a single desk allows Australian farmers to exploit market power. Given that Australia is not in a particularly dominant position as a wheat exporter, this notion has to be called into question, in spite of the AWB's contention that it can exploit market power in particular instances or contexts.

It has to be noted that for a range of other Australian agricultural commodities, the abolition of the single desk has brought about major benefits, including product innovation, higher returns, and significantly -- no reductions in export prices. No convincing arguments have yet been mounted as to why same would not apply to wheat as well.

The AWB itself commissioned Econtech to produce a report on the benefits of the single desk arrangements. The report suggested that current wheat exporting arrangements were positive in their effects and were delivering a premium to producers of between $80 million to $200 million per annum. (4) However, two other studies alluded to by the Productivity Commission are contrary to these findings -- in contradiction to the AWB report both found that reform of wheat exporting arrangements would see welfare gains potentially in the hundreds of millions of dollars. (5)

Because the AWB is a monopoly, it has less incentive to perform due to lack of competitive pressures. Through its position as the monopoly exporter, it may also raise domestic prices of wheat above where they would be otherwise, which is bad for domestic consumers. If the single desk was abolished, farmers would not be left on their own -- there would be nothing to stop them from continuing to use the AWB if that was their preference. However, there would also be other companies farmers could turn to that would compete with the AWB for the provision of services, and competition between these firms would drive down costs, generate improved customer service quality, and lead to a better outcome for Australian wheat producers. It would be barely conceivable that other firms competing with the AWB would not be able to provide at least the same (if not superior) service to wheat growers as the AWB currently does.

The abolition of the single desk would produce higher export prices, more innovation, and better customer service for wheat growers, as has occurred with the abolition of the single desk for other agricultural commodities. The AWB monopoly should be abolished.

3.4. PHARMACEUTICAL RETAILING

Pharmaceutical retailing is one of the most important public policy issues facing Australian policy makers today. Both technological breakthroughs that lead to the creation of new but expensive drugs, and an ageing population likely to become increasingly dependent on the use of these drugs, mean that the amount spent each year on pharmaceuticals in Australia is going to continue to grow over time. Through the operation of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), the provision of drugs represents a substantial drain to the taxpayer as well. For this reason, it is a critical that these drugs are provided as efficiently, cheaply and safely as possible.

There are a number of regulations in place, particularly with regard to ownership restrictions, however, that are presently undermining these goals. State governments at present restrict ownership of pharmacies to qualified pharmacists, and also place restrictions on the number of pharmacies any one individual can own. Supermarkets and other retailers are prevented from offering pharmacy services. Furthermore, the Commonwealth Government restricts the number and location of pharmacies that are allowed to dispense PBS drugs. The reasoning behind these restrictions are to contain the costs of drugs supplied under the PBS, promote as wide as possible access to pharmacy services, and ensure safe provision of drugs to consumers.

The above restrictions however undermine competition, with the result that higher prices are charged to consumers for pharmacy services while not helping with the attainment of those other objectives such as access to pharmacy services or safe drug provision. Location restrictions mean that there is a misallocation of pharmacies with not enough where customers would ideally want them (in large shopping centres for example). The present location and ownership rules not only discourage co-location of pharmacies which would encourage competition and lower prices, but also make it difficult for pharmacies to the achieve economies of scale that would also facilitate lower prices for consumers.

The abolition of ownership restrictions would introduce competitive forces into the pharmaceutical sector and hence reduce prices and improve the quality of customer service. In a report commissioned by Woolworths, the economic consulting firm ACIL Tasman found that if supermarkets were allowed to operate in-store pharmacies, potential cost savings could reach over half a billion dollars per year. This corroborates experience from the UK, which showed that deregulation had resulted in a thirty percent cost reduction on some pharmacy-only medicines.

Furthermore, it is likely that allowing supermarket pharmacies might actually increase access to these services to rural Australians. The Productivity Commission has suggested that by exploiting the economies of scale that supermarkets provide, supermarket pharmacies could possibly reduce the minimum population size required to support such a pharmacy service, thus possibly improving access in rural areas. Allowing supermarket pharmacies might also facilitate longer opening hours, which would not only be of benefit to consumers, but might also at least in part balance any loss of jobs caused by the efficiency gains of deregulation.

The Pharmacy Guild is concerned that concern for quality of service and safety might be undermined by the opening up of the pharmacy sector, stating that organizations like supermarkets would be more concerned with profits than pharmacist owned pharmacies who would always put the consumer first. On the face of it, this seems like a strange argument to make -- why would a salaried pharmacist working in a supermarket be more likely to compromise their professional integrity than a pharmacist/owner who would stand to personally profit from the dispensing of drugs? In any case, there is no evidence that this has been a problem in overseas jurisdictions with a deregulated pharmaceutical retailing sector.

In summary, the deregulation of pharmaceutical retailing should be made an urgent priority for both the Commonwealth and State Governments.

4. COMMONWEALTH / STATE REGULATIONS

Cooperative federalism has meant areas like occupational health and safety and building codes are coordinated at a Commonwealth level so that they are consistent across Australia. In this respect the Commonwealth has certain responsibilities and controls over regulations, particularly in these two areas.

4.1. BUILDING REGULATIONS

Over the past two decades, what is now called the Building Code of Australia (BCA) has developed from different state codes that were less than consistent with one another.

A major deregulatory thrust took place in the 1980s when the states agreed to shift the Code requirements onto a non-prescriptive basis with certain approaches given a "safe harbour" deemed-to-comply status. At the same time the Code itself was re-written in plain English. This allows cost savings in building construction by

- permitting the innovative use of alternative materials and forms of construction or designs while still allowing existing building practices through the Deemed-to-Satisfy Provisions;

- allowing designs to be tailored to a particular building; and

- being clear and providing guidance on what the BCA is trying to achieve.

However, in response to regulatory pressures, the Code has been diverted into a more regulatory set of measures over recent years. Two areas of particular concern are with respect to energy conservation and to promote better access for people with disabilities.

4.1.1. Energy Regulations and House Building

In 2003 the Australian Building Codes Board (ABCB) introduced energy efficiency requirements for Class 1 buildings -- i.e. detached houses -- into the Building Code. This has proven to be a mere start of a steadily escalating process. Jurisdictions are competing with each other to introduce escalating regulatory measures on house construction for energy saving.

The most onerous is the Victorian "5 Star" energy saving regulations for housing.

The measures have brought considerable scrutiny including from the Victorian Government's regulatory watchdog, the VCEC. There is now a strong consensus that the costs are far in excess of those originally envisaged. Research covering 600 builders by the research firm Chant Link conducted jointly for the HIA and the Building Commission found that only 27 per cent of the builders contacted said they needed to make no changes to their designs as a result of the regulation. Of the rest, the most frequently technical changes made to address the Star rating energy efficiency standards were:

- Increase insulation (mentioned by 46% of the sample).

- Use of double glazing (28%).

- Modifying window sizes (24%).

- Changing the building orientation (22%).

- Changing building materials (15%).

- Making water savings (12%).

- Replacing timber floors with concrete slab on ground (11%).

- Over one quarter (27%) said no changes were needed to the home designs they were building prior to the introduction of 5 Star ratings.

The Productivity Commission examined the many cases offered in favour of regulation, such as informational asymmetries, split incentives, ignorance and myopia among others. For the non-externalities that are often at the core of regulatory requirements and strictures the PC suggested that the benefits were very small.

With regard to Victoria's 5 Star Energy Regulations the report said

... evidence is now appearing of compliance costs being much higher than expected. For example, the Victorian Government predicted that the cost of a new house would rise by 0.7-1.9 per cent, but a recent survey shows that the average cost increase has been 6 per cent. And a survey by Master Builders Australia of its members revealed that the cost of a three-bedroom brick-veneer dwelling had increased by between $13 000 and $18 000, depending on design and location. In comparison, the Victorian Government had predicted an average cost increase of $3300.

The PC added,

Energy savings are also uncertain because standards can be difficult to enforce; there are various compliance methods and they lead to different energy savings for a given building and occupant; and standards are not specified in terms of energy consumption.

Energy saving regulations are a clear case of regulatory reflex actions that are imposing considerable costs on the economy. Because they focus on the least affluent sections of the community (and those who are unaware of and politically disorganised to counter their impact) their impact is all the more regrettable.

No further regulations aimed at energy savings should be proceeded with and existing ones should be critically reviewed to determine their merit.

4.1.2. Energy Regulations in Commercial Buildings

A further area of market failure which Code proposals seek to address arises from the fact that building owners do not in all circumstances have incentives to specify optimal levels of thermal performance. This problem is said to arise particularly in relation to rental accommodation. Buildings are complex products and it is likely that, in many cases, owners will not be able to retrieve the marginal costs of specifying higher levels of thermal efficiency from tenants in terms of higher rents. That is, energy efficiency represents only one small element of the bundle of "goods" that a prospective tenant obtains by renting an apartment and so preferences for greater efficiency are unlikely to be translated into effective demand in the market place.

The wrong conclusions can be drawn from such starting positions. Thus it is often argued that a developer who intends to sell a house or building is not concerned about the ongoing energy costs that the occupier must bear, except to the extent that purchaser preference for higher levels of efficiency is translated into higher sale prices. Again, because of the complex "bundle" of characteristics or services effectively provided by a building, the ability of consumers to express effectively their preferences for higher levels of thermal efficiency may be limited in practice. That is, market failure may derive from demand signals not being effectively perceived by suppliers. Alternatively, the complexity of the services provided by buildings may mean that consumers are not sufficiently informed about the impact of thermal performance on running costs and comfort levels and, as a result, do not express a demand for higher levels of performance.

Regulatory implications stemming from these sorts of arguments are highly suspect. In fact building owners need to attract customers and develop an attractive amalgam of features and cost savings to maximise their profits by developing appealing packages. There is no less likelihood that the builder as the "agent" of the renter or subsequent owner is any less careful in this than the designers and builders of other complex purchases like cars or trucks. As the Productivity Commission has demonstrated, the evidence that there might be market failure as a result of a difference of interests between owners and renters is far from convincing.

The Commonwealth should abandon all plans to introduce energy savings requirements into commercial buildings.

4.1.3. Regulations to improve access to commercial premises for people with disabilities

There is a proposed Disability Standard for Access to Premises (Premises Standard), which is intended to codify the general requirements of the Australian Government's Disability Discrimination Act 1992. The DDA prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities in a range of contexts, including access to premises. The technical requirements of the Premises Standard would also be adopted as part of the Building Code of Australia.

The proposed Premises Standard would include specific requirements aimed at providing greater access to premises for people with mobility disabilities, as well as people with vision and hearing impairments. Matters that would be regulated include ramps and doorways, corridor widths, lifts, sanitary facilities, seating spaces in auditoria, car parking spaces and provision of signage.

It would affect virtually all new commercial building, valued at around $15 billion per annum and refurbishment valued at about $8 billion per annum.

It is believed that the standard, if adopted for commercial buildings would lead to costs in the hundreds of millions per annum and mean that many buildings would be less useful as a result of the spatial and access reorganisation that would be required of new buildings and buildings subject to refurbishment.

The measure is aimed at those with disabilities especially those within the workforce. Frisch (8) points out that the 80,000 wheelchair users in the community between 15 and 65 years old have a workforce participation rate of only 38 per cent compared with a rate of 76.9 per cent for those without disabilities. Unfortunately, a rigorous review of the outcomes by Schwochau and Blanck (9) indicates that the US regulations introduced with the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 have failed to increase employment levels among people with a disability. This is supported by research by the National Organization on Disability/Harris (10) which indicated that 29 per cent of individuals with disabilities were employed in the survey of 1998 compared with 31 per cent in 1994 and 34 per cent in 1986.

The failure of US regulations to improve employment levels among people with a disability may be due to a regulation's inability to address on-going reluctance on the part of employers to hire people who, once hired, may require special and costly facilities in workplaces that would not otherwise be required.

In sum, empirical data does not provide substantial evidence of equivalent legislation having achieved the effects sought of Australian regulations. The Frisch suggestion of a doubling in employment rates for users of wheelchairs would seem to be unduly optimistic. The benefits of the regulatory proposals are correspondingly reduced.

Governments should not proceed to regulate with the proposed "premises" standard to require buildings be more "useable" to the handicapped.

4.1.4. Regulations to improve access to housing for people with disabilities

The Australian Building Commission Board is investigating requiring all houses incorporate features that make them more accessible to people with disabilities. Many advocates argue that better design inputs can deliver accessibility at no additional cost compared with current practices.

The sort of features that are valued to promote accessibility include, wider passageways, step less entry, larger bathrooms with grab handles and other features that facilitate wheelchair use, graded pathways, and so on. Often these features are easier to incorporate into larger dwellings and Australian norm of single storey houses makes one feature of these, a downstairs toilet, automatically easier to accommodate than in most other countries.

There is a great deal of literature on the costs for and the need for such regulations. This turns partly on the costs being allegedly trivial. However there is evidence from the government housing authorities (which commission a considerable part of the housing that is specifically geared towards the needs of people with disabilities) that the costs are at least 4% and up to 20% to build in ways that are fully compliant the relevant Australian Standard (AS4299 Part C).

Some argue that as we age we will increasingly value the features of accessibility and we need to be saved from our decision framework myopia. This may be so but it should be left to individual choice. A house is among the most important purchases that we make. If we do not weigh up the various options available to us and the budget constraints facing us with this purchase we can never hope to do so for others. In abandoning consumer choice and substituting the decision taking of experts we are abandoning the free market. Moreover, as with so many features impacting upon housing, the impact is on the new home owner. Not only is this segment of demand less affluent than others but it would also be less likely to value the costs that make housing more accessible or liveable to those with disabilities.

No regulations of housing to require "accessible" or other features to cater for the needs of people with disabilities should be introduced.

4.2. WORK SAFETY AND COMPENSATION LAWS

Most people running businesses in Australia would describe workers' compensation and occupational health and safety (OHS) laws as two of the most frustrating and confusing a reas of government regulation. The laws frequently fail to provide clarity and are, for the most part, inordinately complex.

This confusion and complexity is made worse because there is a high level of inconsistency in regulatory design, approaches, systems and administration between the States. This inconsistency is not being addressed by the States.

Existing workers' compensation and OHS schemes directly and unnecessarily increase operating costs, dampen productivity and constrain business success. Further, the key national priority -- targeting safe working arrangements and compensation for genuine injuries across Australia -- is compromised.

What needs to be understood is that a significant percentage of the systemic problems directly flow from a fundamental design flaw, namely the conceptual underpinning of the schemes by employment concepts. If this design flaw is not addressed the systemic problems will remain.

National leadership on these two issues should be viewed as a priority.

4.2.1. A Flawed Conceptual Framework

Most analysis of OHS and workers' compensation problems focuses on the details of how the various schemes across Australia are administered. That is, the usual focus is on "red tape" compliance issues associated with the schemes. This, however, is inadequate, because both regulatory areas suffer from a key flaw in the conceptual framework with which all state schemes operate. It is this which is at the heart of the compliance problems.

Both OHS and workers' compensation take as their starting point the elements of control which are embedded in the employer-employee legal relationship. The crucial feature of this relationship is that the employer has the "right to control" the employee. The inference contained within the legal relationship is that the employer is all powerful in the work relationship and, further, that the employee is in most respects powerless. The legislative structures of OHS and workers' compensation are both predicated upon the existence of the employment relationship and it has, therefore, come to dominate the cultures and administration of the institutions that administer the laws.

This results in a number of assumptions being built into the design of regulations that are highly suspect when it comes to practical work realities.

Those assumptions are that:

- When a work injury occurs, the employer, however defined, is responsible for the injury.

- Employees have diminished capacity to control the work environment and, when an injury occurs, are assumed to be blameless.

Thus, the employer (however defined) is presumed to be at fault regardless of the actual causes of any particular injury. This distorts the effective functioning of workers' compensation arrangements as insurance schemes and OHS laws as injury-prevention mechanisms.

This is the starting point from which the policy and operational distortions that occur in workers' compensation and OHS laws can most readily be understood.

4.2.2. The Issue of "Control"

The closest public policy parallel to workers' compensation and OHS laws are the road laws. By contrasting the two areas, the inconsistencies in public policy approach become clear.

Both road laws and work safety laws have to consider "who controls the situation" in order to create effective rules which (a) reduce the incidence of injury and (b) facilitate enforcement.

However, when it comes to the funding and administration of the rehabilitation of injured individuals:

- who controlled the vehicle and caused an injury is not taken as relevant under road laws but,

- who is assumed to control the work situation is central under work injury insurance laws.

4.2.2.1. Road Laws

For example, road laws operate on a practical basis that drivers control vehicles and are held personally liable for their driving behaviour. But, unlike property insurance, compulsory personal injury insurance for vehicle-related accidents does not apportion blame. In fact, to apportion blame for personal road injury insurance purposes would distort the operation of this insurance.

Road laws clearly stipulate what drivers can and cannot do. It is recognized that if the laws are ambiguous or confusing, this will result in car crashes. Drivers are held responsible for their individual actions over what they personally control. Serious breaches of road laws resulting in crashes, death and/or injury can result in criminal charges being laid with possible imprisonment as punishment. Manufacturers of vehicles are required to supply vehicles to minimum regulated safe standards, given technical limitations.

With car insurance, when crashes result in personal injury, the insurance schemes operate on a no-fault basis (this is different to non-compulsory property insurance). All vehicles must be insured for personal injury cover, individual premiums are not adjusted according to claims history, and all injured persons are treated equally and have access to medical, compensation and rehabilitation services. Even a driver who may have caused a crash is not denied medical insurance services.

This system works well and is accepted as fair and just because the individual who controls a vehicle is easily identified. If fault is to be apportioned under the road laws, this is tied to the discovery of facts. Drivers are not held to be liable for situations beyond their practical control. But control and blame are not relevant for the purposes of rehabilitating injured persons.

4.2.2.2. Work safety

Under work safety laws, however, the apportionment of blame dominates. Work safety laws take it as given that the employer controls the work situation and is therefore responsible and liable under both workers' compensation insurance and OHS.

But the reality of work situations is that many different individuals have combined control over work. The truth is that there are normally multiple "hands" on the steering wheel of the work "vehicle". Work safety laws, however, are biased toward the assumption that only one "hand" -- the employer's, controls work. This is a false assumption based on the presence of a legal contractual relationship called employment. The truth is that employers do have significant control, but so too do employees and many others, including unions, suppliers and government authorities.

The outcome of this false assumption about employer control is that:

- Individuals who did not have practical, effective or total "control" are held to be totally liable, both from an insurance perspective and a prosecution perspective.

- Other individuals who did have control or shared control in any situation are not held liable in any respect.

Twisting the truth about "work control" in such a contorted way diminishes community trust in the fairness and justice of work safety laws, causes people to spend time and energy trying to avoid the injustices of the laws, and reduces the effectiveness of public policy targeting safe work.

Further, this key conceptual point -- "employment control" -- if ever it was valid, is quickly being deconstructed by the rapid rise of independent contracting which organizes work without using the employment contract. The response of work safety regulators to this development has been to further distort the law by selectively and inconsistently "deeming" some non-employees to be "employees". This process has layered regulatory confusion upon confusion to the point where the "road laws" of OHS and workers' compensation cannot effectively be known in advance by the community. This confusion of work safety "road laws" must, of itself, work against safe work.

The extent to which this confusion and distortion occurs varies from State to State, thereby creating further confusion. Some States, however, have made positive developments to have the law reflect work realities and create clarity. Other States have actively distorted the law.

4.2.3. Occupational Health and Safety

Occupational Health and Safety laws vary widely between the States in terms of their core structure and definitional approach. NSW is the worst of the states; Victoria is probably the best. The other States have variations on a central theme perhaps closer to the Victorian approach than to NSW. The legislative approaches to the imprisonment of individuals for unsafe work practices, varies markedly between the States.

4.2.4. Core legislative structures

The international benchmark for OHS laws are established under the Robens principles of the UK, and ILO Convention 155. These hold that individuals should be held liable and responsible under OHS for what they control within the bounds of what is practicable.

4.2.4.1. Victoria

Victoria established new OHS laws in 2004 which closely reflect the international principles.

- All parties are held responsible for what they practically control. This applies equally to employers, employees, independent contractors, suppliers of equipment, controllers of premises and so on.

- Prosecutions and fines apply in equal measure to all individuals, regardless of their particular legal status.

Victoria has largely resolved the problem of assuming that "control" is tied to the employment relationship. Victoria has "looked through" the legal status and applies practical measures based on the facts of any given situation relating to the parties who exercise work control. In other words, employees have the same measure of responsibility and liability as employers according to what they practically and actually control. The same applies to suppliers and others.

This sends powerful signals to everyone in Victorian work situations that they have personal and individual responsibilities to conform to safe work practices.

4.2.4.2. NSW

NSW has grossly distorted the international OHS principles and, in so doing, has created significant community distrust of their OHS laws.

The NSW approach is an extreme case of where the laws assume that the legal status of the employer results in the employer being assumed to be in total control of work. In doing this, the NSW laws effectively strip employees of any individual responsibility to comply with statutory OHS responsibilities.

In NSW:

- Employers, independent contractors, suppliers of equipment and so on have a statutory obligation to ensure that no injuries or deaths occur. There is no tempering of this in terms of what is practical or what they in fact control.

- This statutory requirement to "ensure" creates presumption of guilt under NSW OHS laws. "Practical control" only applies as a defence. This is a distortion of international OHS principles rather than an application of them. In particular, the statutory presumption of guilt has led to a serious lack of confidence in the justice and fairness of NSW's laws.

- Employees do not have a specific statutory obligation to comply with OHS laws. Employee obligations are limited to "co-operating" with the employer's obligations. This effectively transfers liability for the actions of the employee to the employer. This creates presumed guilt on the part of an employer, even if the breach of OHS laws occurred because of the negligent actions of an employee. This sends powerful signals to employees that they can ignore OHS obligations, and equally powerful signals to the community that the OHS laws defile justice. This strips the NSW laws of integrity.

Further compounding this defiance of international OHS obligations, the NSW laws:

- Conduct prosecutions in the IRC jurisdiction, as opposed to proper courts as applies in all other States.

- Deny access to trial before jury.

- Prevent full rights of appeal in prosecutions relating to injuries and fines.

- Allow unions to act as prosecutors and to receive up to half of the fines imposed and have their legal fees paid by the party prosecuted.

As a consequence, these laws have bred an aggressive prosecution culture within the NSW Workcover authority. This is highlighted by the fact that NSW conducts over 60 per cent of OHS prosecutions Australia-wide, but has only one-third of the Australian workforce. Further, 65 per cent of Australian OHS convictions occur in NSW.

4.2.4.3. Other States

No other State has OHS laws as distorted as NSW. Instead, they all have a general application of international OHS principles but with variations in their legislative structures. The emphasis is on control within the bounds of practicability. None has applied presumption of guilt. But none has gone as far as Victoria in making it absolutely clear that employees as individuals have equal OHS responsibilities and liabilities alongside all other individuals -- regardless of legal or contractual status.

4.2.5. Unions

All States grant unions some form of special OHS authority, including access to workplaces. NSW is the only State that gives unions prosecutorial powers.

Union special privileges for OHS purposes are generally justified on the grounds that employees need a safety voice "on the ground". Unions are chosen because historically they represented a large proportion of employees in the workplace. With the collapse of union membership and the rise of independent contractors, however, special OHS privileges for unions in fact act to dis-empower employees' OHS voices. This is dangerous for work safety objectives.

No State government has adequately discussed or addressed the issue of how to ensure effective worker OHS empowerment in the face of an ineffectual union presence or a union presence that may work against OHS. State governments' OHS laws have requirements for OHS committees but these are predicated on the use of collectivist structures and fail to address the needs of individuals. It is a gaping hole in OHS regimes.

4.2.6. OHS and criminality

All jurisdictions have the normal processes of criminal liability applying alongside OHS laws. This replicates the road laws. That is, if an individual knowingly and/or with gross negligence does something that leads to the injury or death of a person in the work situation, the individual can face criminal prosecution through the normal criminal courts and with all the rights of criminal justice applying.

Over the last decade, however, there has been a strong push to embed additional criminal or quasi-criminal sanctions inside OHS laws. This is not consistent with international OHS principles. Such laws distort justice.

4.2.6.1. Commonwealth Criminal Code

In 2001 the Commonwealth amended the criminal code creating something called "corporate criminality". Effectively, the Commonwealth has put into legal force the idea that a collection of individuals (for example, a corporation) is able to commit a criminal act. The code holds that a corporate "culture" can act criminally. This is a breach of well-established principles of criminal justice which hold that only individuals are criminally responsibly for their individual actions. "Cultures" are never held to be capable of criminal actions. Further, the Commonwealth Code holds that individuals within corporations can go to jail on behalf of the corporate collective. That is, that an individual who has not been found to have acted criminally in his/her own actions can be jailed for the criminal actions of others.

4.2.6.2. Victoria

Shortly after the Commonwealth created the code of corporate criminality, Victoria attempted to translate the code into work safety laws. That is, it attempted to legislate that a corporation would have been declared to have acted criminally and corporate executives were to be jailed on the corporation's behalf. This attempt at OHS corporate criminality was rejected. In 2004, however, Victoria reviewed its OHS laws. The Maxwell Report rejected corporate criminality and the idea that criminality can apply to OHS laws. The report did, however, recommend jail for flagrant breaches of OHS laws -- even where an injury or death does not occur. The 2004 Act adopted the recommendation. The reasoning applied is that serious breaches of OHS laws can lead to injury and death and, as such, jail might be warranted in extreme cases. It is not immediately clear but probable that the normal processes of criminal justice would apply.

4.2.6.3. ACT

The ACT has applied a modified version of corporate criminality in its OHS laws based on the Commonwealth Criminal Code. The Commonwealth, in response, has moved to remove Commonwealth corporations from the application of the ACT Act, while at the same time retaining its own code of corporate criminality. On this issue, the Commonwealth is displaying policy inconsistency and confusion without explanation.

4.2.6.4. NSW

NSW provides for imprisonment of individuals when death or serious injury occurs. For second offences under its 2000 Act, presumption of guilt applies, trial is before the IRC, trial before a jury is denied and full appeal rights are denied. Imprisonment for first offences applies under its 2005 Act, with presumption of guilt and trial before the IRC. Trial before a jury is still denied, but full appeal rights apply.

4.2.6.5. Other states

Queensland, Tasmania and the Northern Territory do not have imprisonment provisions in their OHS Acts but retain that possibility under criminal laws. The other States have not enacted OHS laws that carry a possible prison term similar to the Commonwealth, Victoria or NSW, but reviews and proposals for such laws are pending in South Australia and Tasmania.

Laws across Australia relating to the imprisonment of individuals under OHS are inconsistent and confusing at best. At worst, as in NSW, they strip Australians of their normal rights to access systems of justice. The NSW laws, in particular, represent vastly more than a "red tape" problem. Rather, they cut to the heart of what it means to be a civilized society. National debate with a view to consistency and proper application of criminal principles is urgently required.

4.2.7. Workers' Compensation

Workers' compensation is distorted by lack of consistency and confusion of intent. The starting point for confusion is definitional inconsistency in the jurisdictional reach of the State schemes. The concept of employment intrudes into the schemes' designs, which results in the distortion of normally accepted insurance principles.

4.2.8. Flawed insurance concepts

The essence of the problem is that the person paying the premiums (ie) the employer however defined does not receive the benefit of any claim but suffers the losses resulting from a claim made by someone else. Under normal insurance the person paying the premium is the person covered and liable to receive the benefit in the event of a claim. It is in this basis that actuarial risk is assessed. However workers compensation design distorts normal actuarial risk assessment.

4.2.9. Definitions

The Heads of Workers' Compensation Authorities insist that workers' compensation benefits apply only to employees and that self-employed individuals cannot be covered by the schemes. However, if self-employed individuals structure themselves as a company, they normally become subject to the schemes by virtue of becoming an employee of their company, even though they are effectively the employer of themselves. Further, the States have all created definitions of employment for the purposes of workers' compensation that go beyond common law and which bring some individual self-employed persons within their schemes and leave others out. There is no consistency in the approach between the States. Both within each State and between the States there is high level confusion about the status of self-employed individuals and entities that engage self-employed individuals for the purposes of workers' compensation.

4.2.9.1. Victoria

Victoria has all-embracing and unintelligible "deeming" provisions which, when tested in the High Court, led the Court to declare that the provision meant whatever the bureaucrats chose them to mean. This has resulted in a situation where individual unstructured self-employed persons are refused workers' compensation registration should they apply. However, entities engaging self-employed persons may be liable to pay premiums on the person they engage, but cannot know for sure unless audited by the Workcover bureaucrats.

4.2.9.2. NSW

NSW will not register self-employed individuals but has a bureaucratic expectation that entities which engage such individuals should pay premiums on the individuals engaged. But the authority will not guarantee that it will honour claims on such individuals, even where premiums have been paid. NSW also lists a variety of occupations where self-employed persons are declared "employees" and subject to the schemes.

NSW is currently undergoing an aggressive audit by Workcover in which businesses that have used independent contractors in good faith are being confronted with retrospective premium bills large enough to cause business closures. Some businesses have, in fact, closed as a result.

4.2.9.3. Queensland

Queensland has a broad definition of worker but then excludes some workers who pay tax under the Federal Personal Services Income Act.

4.2.9.4. South Australia

SA does not cover self-employed individuals in their scheme but because the workers' compensation jurisdiction is handled by the IRC, there is a bias toward creatively finding individuals to be "employees". This has created significant and expensive litigation. People working in certain occupations are also declared to be employees for the purpose of the scheme.

4.2.9.5. Western Australia

WA applies a broad definition of worker but excludes directors of companies from the scheme. That is some types of employees (directors) are excluded but other types of independent contractors are included.

4.2.9.6. Northern Territory

NT applies a broad definition of worker but in some instances exclusions can apply by regulation.

4.2.9.7. Tasmania

Tasmania takes a practical approach to the issue. If self-employed individuals have evidence of private accident/illness cover, they do not have to register or be covered by the workers' compensation scheme. If no insurance cover is evident, an entity engaging the self-employed individual must pay workers' compensation premiums and the person is covered. Tasmania has eliminated confusion through a simple administrative trigger that ensures that all working individuals have work insurance cover of some sort.

4.2.10. Fraudulent claims

Because the systems work on the assumption that the employer is to blame for injury, all State systems are wide open to claims abuse. Workcover authorities claim that they investigate fraud. In practice, however, the systems are often rorted. The systems are seen by many as a supplement to social welfare.

Endemically:

- Workers who may have suffered an injury out of work will claim the injury was work-related. The systems assume that when a claimant alleges the injury was work-related that the worker is correct. The onus to prove the injury was not work-related falls on the employer -- an almost impossible task.

- Some sections of the medical profession are complicit in fraudulent claims. Most medical professionals charge more for a workers' compensation consultation than for other consultations.

- Non-declaration to employers by employees of prior injuries is standard. If re-injury occurs, the employer is required to bear the costs. Workers' compensation authorities claim that non-declaration of prior injury can void a claim, but this rarely, if ever, applies. Privacy, discrimination and other laws effectively prevent employers from investigating if a prospective employee has prior injuries. This stops employers from having proper control of their work risk. Yet they must bear the cost of claims.

4.2.11. Claims Management

The employer is supposed to undertake claims management. This occurs also because of the assumption that the employer is to blame and as such should shoulder the responsibility of claims management. The systems in place, however, are hugely complex and require dedicated and specialist skills. For small businesses, in particular, claims management administration is overwhelming in its volume and complexity. The systems work badly. Employers are supposed to be assisted by workers' compensation authorities and/or contracted insurers, but these organizations suffer from high turnover of claims-management staff, internal lack of knowledge of claims-management rules and processes, and inconsistent and often contradictory application of claims-management rules.

4.2.12. Return to work

Employers have obligations to assist injured workers to return to work. However, the risk of aggravation of pre-injury creates high level risk for employers in effectively being able to facilitate return to work, particularly for individuals who have lingering injuries. Return-to-work processes require highly skilled specialist medical knowledge to effect properly. The complexity for business is extreme and beyond the skills base of most employers.

4.2.13. Recovery or the "no" policy policies

The use of on-hire (labour hire) is common in workplaces. In all jurisdictions, the on-hire company is required to cover the on-hired workers for workers' compensation, pay premiums and manage claims. The on-hire agencies include the cost of workers' compensation in the charge rate to their clients.

In the event of claims, however, workers' compensation authorities regularly initiate "recovery". They sue the client of the on-hire agency for the cost of a claim and "recover" the money -- usually from the client's public liability insurer. Over the last three years, workers' compensation authorities have aggressively followed this course of action.

The outcome is that:

- The authorities "double dip", shifting the cost of workers' compensation on to public liability insurers.

- Workers' compensation schemes have become a sham, effectively involving State-legislated theft from businesses whereby worker injury insurance premiums are charged, but the cost of the benefit in the event of claims is transferred away from the scheme to another party.

- Public liability insurance companies have become reluctant to provide cover to companies that use labour hire.

It is possible that recovery is being used by State governments as part of a campaign to force businesses not to use labour hire.

However and in addition, recovery is being used against apprenticeship group training companies putting at risk the national apprenticeship system.

4.2.14. OHS Conclusion

The chief feature of Australia's OHS and workers compensation schemes is their inconsistency. Within each state the schemes are predominantly complex and difficult to understand for both businesses and workers. Some States are better than others. Some States have made quality improvements.

However, for businesses that trade in single states the compliance issues are huge. For businesses that trade between states the compliance issues are arguably insurmountable. It is perfectly feasible to face OHS prosecution in one State and not another for identical occurrences. It is perfectly feasible for a worker to be injured in one State and be covered by a workers compensation scheme but for the same worker to suffer an identical injury in another state and not be covered.

This situation works against the national objective of safe work environments and effective worker injury management schemes.

4.3. FREEDOM OF INTERSTATE TRADE

Freedom of inter-state trade is a defining characteristic of Australia as a nation and is required by section 92 of the Constitution. If a state creates a regulatory structure that impedes interstate trade it is arguably acting unconstitutionally. In principle there are many shades of unconstitutionality. The most extreme example would be a customs duty levied at the borders, the more normal form by which such measures were put in place during the early 20th century.

As trade barriers were eventually reduced and eliminated, other barriers, usually grouped under the acronym NTBs -- non-trade barriers -- started to assume greater importance. They did so partly because modern technology allowed such measures to be employed, and partly to overcome the declining ability to use formal tariff based trade barriers.

One significant NTB often employed the growing power of government procurement under which purchases were required to be sourced from local suppliers. In some cases, states have insisted upon specific state endowed regulations for some service providers to operate. Such measures have been steadily reduced over recent decades and more-or-less eliminated as a result of the Competition Policy reforms.

Beyond this, there remain some state based measures that effectively deny inter-state suppliers the ability to compete. For example, in some cases, states apply quarantine measures with what would be regarded as excessive rigour in international trade relations. Parochial concerns are excluding the sale of goods that are lawful in one state from being sold in others. A case in point is genetically modified (GM) food. Dozens of varieties of GM products are available worldwide. As of June 2005, the Australian Government's food safety regulator, Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) had approved 25 GM crops. Of these, cotton varieties are the only commercial GM crop in Australia; potato and sugarbeet varieties, although approved, are not being grown in Australia or overseas.

Regulatory denial of these products, especially in the face of their clearances by the competent federal body (and by all other scientific authorities) is not only a regulatory restraint on productivity, but is also a restraint on trade between the states

Similarly, in order to abide by an idiosyncratic requirement, house building design may need to be modified in quite substantial ways. It will be recalled that the Chant Link research undertaken by the Building Commission and the HIA found that only 27 per cent of the 600 builders contacted said they needed to make no changes to their designs as a result of the Victorian "5 Star" regulation.

Measures like 5 Star Energy requirements introduce regulatory restraints to trade which would doubtless deter some firms, especially those for which Victoria is not presently a major market, from offering their product in that State. Not only does the cost increase result in a re-arrangement of competitive profiles and a diminution in consumer benefit, but it reduces the competitive pressures on suppliers and thereby blunts the process by which innovations and efficiency driving measures operate.

States should re-affirm the principle of freedom of inter-state trade. (11) They should agree to the PC hearing cases on where regulatory measures taken by one state may be contrary to the provisions and cease activities that are so found.

5. STATE BASED REGULATIONS

Over the past two decades the nature of regulations has changed. When the Hawke Government launched its major push against over-regulation in the early 1980s, tariffs and their equivalent Australian industry protection have been reduced from 24 per cent to 4 per cent over the past thirty years. We have seen the ending of the enforced cartel and price controls in airline operations, the ending of monopoly gas and electricity supplies, and the termination of price controls and export controls on a range of goods and services. National Competition Policy gave this process a final push during the 1990s but it was well underway before then. We are also now seeing an acceleration of moves to deregulate the labour market.

A great deal of the regulation that was removed as part of the microeconomic reforms of the 1980's and 1990's concerned "economic" regulation. This regulatory field encompasses price controls, the conferring of monopoly rights and impediments to market entry. Over the same period of time, however, there has been no corresponding let up in "social" regulation: environmental measures, safety requirements, health based restraints and measures targeted at deceptive conduct. The growth in the overall regulatory burden in Australia is almost exclusively a matter of the accelerating trend in these social regulations outpacing the dismantling of economic regulations.

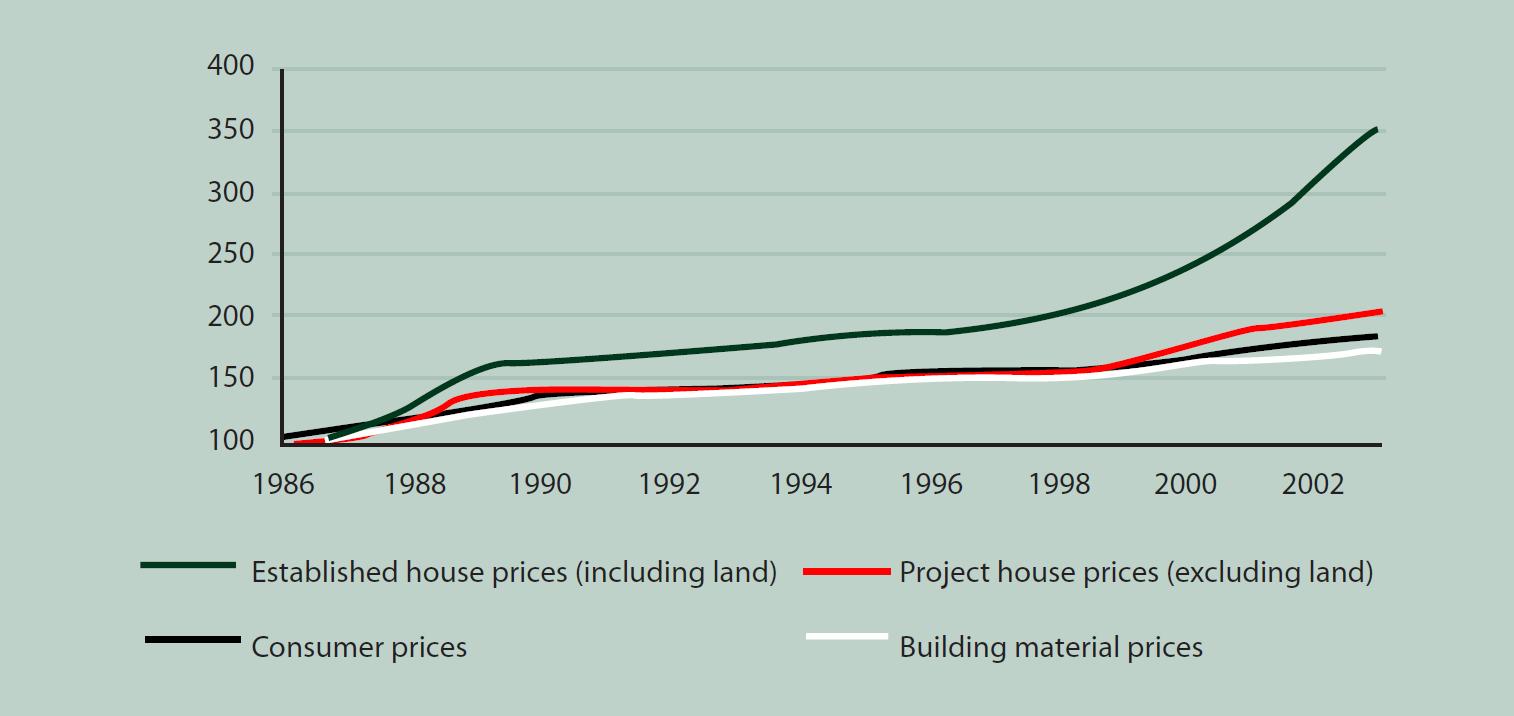

One regrettable lapse in this respect has been in land use regulations. Throughout Australia, state and local authorities have placed serious restraints on new building. These restraints have been particularly severe in NSW with the previous Premier placing a high priority on restraining population growth, but the same general trend is evident throughout Australia. As a result, although house building costs have been kept at around the general level of prices (an achievement in view of the increased regulatory impositions on the industry and the fact that new house sizes have gradually increased), new homes have risen markedly in price.

Housing Cost Increases, 1986-2002 Source: ABS (Consumer Price Index, Australia, Cat no. 6401.0,

Source: ABS (Consumer Price Index, Australia, Cat no. 6401.0,

House Price Indexes: Eight Capital Cities, Cat no. 6416.0

This is illustrated in the chart "Housing Cost Increases, 1986, 2002".

The land component, which in 1976/7 comprised 32% of a new home in Sydney, now comprises 62% in 2005. Other capitals have fared little better. This has been mainly due to the squeeze on land availability originated in misplaced desires to prevent "urban sprawl".

Australian house prices are now, in terms of multiples of household income levels, among the highest prices in the world. (12) There are some hopeful signs for reform in this area, not least of which were comments made by the Prime Minister on the issue at the HIA conference in November 2005 (13) calling for an expansion of land availability. The Victorian Government has also responded by announcing a considerable expansion of land availability in an effort to drive down prices. Unfortunately, the Victorian Government is to take advantage of the land price boost its policies have caused by also introducing a new tax of up to $8,000 on each new housing lot.

This will, in part, negate the benefits of the expanded release program.

While the Commonwealth has a role in social regulations and has proven to be no slouch in introducing its own, these mainly fall within the powers of state regulators.

6. GOVERNMENT POLICIES TO COMBAT OVER-REGULATION

All jurisdictions could improve their handling of regulation. Following are some recommendations that should be required prior to new regulations being introduced:

- Require a review to ensure the new regulation is fully consistent with the letter and spirit of the freedom of inter-state commerce provisions of the Constitution

- Introduce the regulation under a two stage process approach: the first simply setting out the issues in an dispassionate and non-committal, manner and the second seeking comment on the agency's preferred approach.

- Require an independent analysis to verify that the regulation is merited. This might be a scientific review in the case of measures mooted that guard against health or environmental externalities. And it may use formalised and independent economic analysis to review alleged economic benefits from an externality.

- Establish disciplines that ensure the regulatory burden does not increase. In this respect a useful approach would be that of the UK Prime Minister's direction to the Better Regulation Task Force to look at:

- First measuring the administrative burden then setting a target to reduce them (the Dutch approach) and

- A "one in, one out" approach to new regulation, which forces a prioritisation of regulation and its simplification and removal.

The Dutch approach has three dimensions. First it involves measuring the burden on business using a standardised approach. They examine the administrative burden only. This is what the US agencies refer to as the paper burden and which typically amounts to 30 per cent of total regulatory costs. According to Crews (14) in his annual assessment of US regulatory costs, those of the federal government amount to 8.7 per cent of GDP.

Crews's assessment is based on long standing analyses conducted by the Office of Management and Budget and goes back to work undertaken by Wiedenbaum in 1979. It is broadly consistent with the Dutch estimate of 3.6 per cent as the cost of the administrative burden alone -- using the 30 per cent rule of thumb this would amount to 12 per cent of GDP but differences are inevitable due to different roles of the US states and the EU. (15) Various studies have been assembled by the PC and its ORR/BRRU satellite which place estimates in the same ball park.

Crews argues that we have very little idea whether the benefits of any of the regulations exceed the costs at present. He considers that legislators have been derelict in allowing regulatory agencies to introduce regulations without proper oversight. He says, "Agencies face overwhelming incentives to expand their turf by regulating even in the absence of demonstrated need, since the only measure of agency productivity -- other than growth in its budget and number of employees -- is the number of regulations. The unelected rule when it comes to regulatory mandates".

To counter this growth, the second arm of the Dutch approach involves setting a target for reduction of the burden -- after an early false start the Dutch have chosen 25 per cent over four years. The focus on the administrative burden was purposely adopted since it would bring about less political opposition (in the event no political opposition) than measures that confront policy head-on.

Finally, the organisational structure must be appropriate. Too many good intentions about reducing the paper burden evaporate after the first flush of press releases.

Though Crews is right that agencies tend to be regulation-philes, in developing new rules they are giving expression to political representatives' broad intentions. Regulation is not simply some abstract body of laws developed by an impersonal bureaucracy. Governments and Parliaments must generally therefore impose disciplines on themselves if they are to reduce the burden they place on the electorate. In the Netherlands the organisational structure to facilitate this involves an independent watchdog body which reviews the calculations of the costs that departments themselves estimate before legislation proposals are sent to Parliament. The Cabinet is also obliged to consider the estimates of costs before endorsing new legislation and each government department has a body of officials with responsibilities designated to reducing the regulatory burden.

As in the US, the regulatory agency falls under the Minister for Finance. Such machinery in principle already exists within the Commonwealth, Victoria and to a lesser degree other states.

Confessing some scepticism about the practical outcomes of the Dutch approach, the UK Better Regulation Task Force found evidence that the Netherlands was in fact achieving its target reduction. The Task Force proposes to marry this with the sloganistic "One in one out" approach. Again the intent is for the government to place a discipline on itself by forcing a search for regulatory economies especially where new regulatory measures are proposed.

Over the past year or so, Victoria has adopted the most rigorous regulatory review machinery with the Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission (VCEC). This is a statutory body, established under the State Owned Enterprises Act, which has the role of acting as the government's primary source of advice on regulatory reform policy. The three Commissioners are statutory appointments and are therefore independent of the government. This model clearly strengthens the Commission's role in assessing the adequacy of RIS's by granting ultimate authority for the function to these independent statutory appointees.

This model is probably superior to the Commonwealth government's Office of Regulation Review because of its independence and a more rigorous requirement it has in place for the conduct and publication of Regulation Impact Statements. The VCEC will normally insist that RIS's be undertaken independently and issued before any legislation is tabled. By contrast, Commonwealth Departments undertake in-house RIS's which are often simply a rubber stamp on a policy that has already been formulated (such as the previously mentioned Energy Efficiency Bill for example).

We would recommend that the Victorian system be generally adopted together with:

- measures aimed at simplifying regulation and consolidating it to make it more accessible (a process that is also likely to make it more internally consistent).

- Sunsetting regulations and putting into place a more rigorous renewal machinery.

- Establishing clear Ministerial responsibilities for regulatory reform. The US lodges its own regulatory oversight body within the Office of Management and Budget (the equivalent to the Australian Finance Department). Some have called for it to be lodged directly within the Prime Minister's portfolio. Either way it must be given robust responsibilities for blocking regulations and for having them reviewed.

- Using regulatory budgets, a variation of the "one in one out" provisions under which departments are forced to hold or decreases the total costs of the regulations.

In addition, it would be most helpful to adopt the proposal put forward by SA Premier Rann to develop a Red Tape comparative assessment for each state and published this annually. Setting up a system of "competitive federalism" in this way would be a most useful propellant for reform and be helpful for the states that have gone furthest in this direction to advertise themselves as such to industry.

REFERENCES

1. World Bank

2. Thomas DiLorenzo, The Myth of Predatory Pricing

3. R. Mark Isaac and Vernon L. Smith, "In Search of Predatory Pricing", Journal of Political Economy, April 1985, pp. 32045.

4. http://awb.com.au/AWBL/Launch/Site/Growers/ChrisMoffetWAFFConference.htm

5. http://www.pc.gov.au/inquiry/ncp/finalreport/ncp.pdf -- p267.

6. http://www.aciltasman.com.au/images/pdf/REPORT_RELEASE%20SAT.pdf

7. Productivity Commission Submission to the National Review of Pharmacy, November 1999

8. The Benefits of Accessible Buildings and Transport: An Economist's Approach, Dr Jack Frisch.

9. Scwochau S and Blanck P.D., The economics of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Part III: does the ADA disable the disabled?, Berkley Journal of Employment and Labor Law vol 21 2000 p. 271-313

10. Chartbook on Work and Disability, National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation

11. The Constitution, section 101, says "There shall be an Inter-State Commission, with such powers of adjudication and administration as the Parliament deems necessary for the execution and maintenance, within the Commonwealth, of the provisions of this Constitution relating to trade and commerce, and of all laws made thereunder". The Inter-State Commission was absorbed into the Industry Commission.

12. See http://www.demographia.com/dhi-rank200502.htm

13. http://www.pm.gov.au/news/speeches/speech1681.html