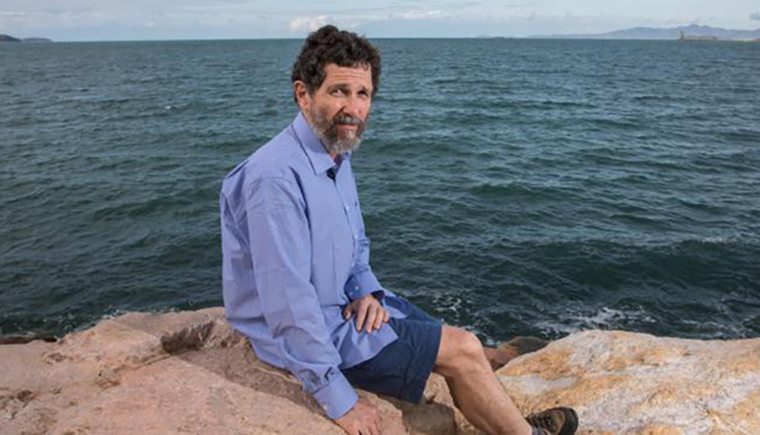

"What happened to me has a massive chilling effect on debate," says physics professor Peter Ridd, who was sacked by James Cook University last week after saying other scientists, including former colleagues, have exaggerated the dangers to the Great Barrier Reef.

"Any scientist who might agree with me on the reef will just keep their mouth shut, it's just too risky."

"Any scientist who might agree with me on the reef will just keep their mouth shut, it's just too risky."

The well-published professor in coastal oceanography, reef systems and peer review, and a former head of JCU's school of physics, allegedly has "engaged in serious misconduct, including denigrating the university and its employees, and not acting in the best interests of the university", according to vice-chancellor Sandra Harding in the letter terminating his employment.

The sacking stems from comments the 29-year JCU veteran made on Sky News that "science is coming out not properly checked, tested or replicated" and those who claim problems with the reef are too "emotionally attached to their subject" — views already aired in his chapter in the book Climate Change: The Facts 2017. Ridd's academic freedom supposedly has fallen foul of the institution's code of conduct. A disturbing pattern is emerging on Australia campuses. The JCU experience is typical of the breakdown of free intellectual inquiry at our universities; of debate replaced by dogma.

"I'm a lefty myself, but a monoculture is always a risk, whether you're part of it or against it," says Bill von Hippel, acting head of psychology at the University of Queensland. "I'm very worried that the left-leaning ideology of most members of our field might skew the nature of the questions we ask and the way we interpret our findings."

Ridd has taken his fight to the Federal Circuit Court on the grounds that termination of his employment is a breach of his contractual right to academic freedom. "We need universities to actually encourage different viewpoints so that we get argument," he says.

I have spoken to more than a dozen Australian academics across disciplines, universities, and the political spectrum who are concerned about the suffocating monoculture that is gripping our universities, jeopardising research and teaching.

These academics are members of Heterodox Academy, a network of 1865 professors from the US, Britain, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia. They come from the political left and right but are united in promoting viewpoint diversity: a range of perspectives challenging each other in the pursuit of reason, truth and progress.

Heterodox is premised on the work of co-founder and chairman Jonathan Haidt, a professor of psychology at New York University. Haidt's moral foundations theory contends that progressives have a more narrow moral palette than conservatives. Progressives prioritise care and fairness; the moral palette of conservatives includes these concerns, in addition to group loyalty, submission to legitimate authority and disgust. Haidt has found that these moral intuitions drive progressives and conservatives to different world views.

This poses a danger for research. Academics, like everyone else, are not immune from confirmation bias (interpreting information to confirm pre-existing beliefs) and motivated reasoning (developing logic to support pre-existing beliefs). To combat these biases, individuals with different opinions need to be put together to "disconfirm the claims of others", Haidt says.

It is necessary for conservative academics to challenge progressive academics, and vice versa. This is the essence of the Socratic method, of claim and counterclaim in pursuit of the truth, and it is what drives intellectual inquiry.

Universities, particularly in the humanities and social sciences, are dominated by progressives. A US study found less than 10 per cent of academics identify as conservative, while another study found 39 per cent of US campuses have no Republicans. The situation in Australia appears to be similar. Universities seek gender and racial diversity but they are missing the diversity that is crucial for their effective functioning: viewpoint diversity.

"When everyone shares the same politics and prejudices, the disconfirmation process breaks down," Haidt says.

Academics interviewed by me tell of a variety of ways that the progressive monoculture limits free intellectual inquiry in Australia. Important projects do not receive funding. Challenging papers are not published. Important issues are not investigated. Studies are designed to reach predetermined outcomes. Erroneous research is misguiding society. Academics self-censor. Administrators censor heretics. Students are exposed to fewer ideas and are marked down or failed for expressing a different perspective.

"Essentially, I was reprimanded for discussing issues that could make students feel uneasy or uncomfortable," an Australian academic tells me on condition of anonymity, fearing retaliation from the university and shunning by colleagues.

This same academic was condemned by university administrators for using challenging stories from Haidt's moral foundations theory in his teaching. The stories, which include necrophilia, incest and cannibalism, are designed to teach students how instinctive emotional responses come before logical reasoning.

"Students are adults, not children, and within a university it should be possible to expose students to material that, even if it was distasteful and confronting, is of educational value," the academic says.

Administrators demanded the stories be removed from a new online course on ethics, despite no complaints from on-campus students in the past. The academic reluctantly agreed to the censorship and thought this was the end of affair. However, word about the stories spread. Several months later the academic was reprimanded again at his annual performance review for teaching "culturally insensitive" stories. He believes he was punished with an increased workload. Cultural sensitivity is the progressive political belief of not offending those of non-Western backgrounds.

"Going down the path of 'cultural appropriateness' recommended by my supervisor is condemning universities to a future of pre-Enlightenment obscurantism. For example, most of my students come from countries where homosexuality is both illegal and subject to social censure. Does this mean that I should no longer discuss homosexuality in my teaching? In conversing with Saudi students I have discovered that some of them believe that women should not hold political office. Should I therefore avoid referring to female politicians in my lectures?"

Ideological monocultures create intolerance and hostility. When you never hear opposing perspectives and spend time only with people who reinforce your ideas, it breeds overconfidence. You come to think that the people expressing opposing perspectives are intellectually deficient or driven by sinister goals.

"If you are exposed to just one set of ideas, you're not going to understand the other person's perspective," Matthew Blackwell, an economics and anthropology student at the University of Queensland, warns from his experience. "And even if they do begin to try to tell you their perspective, because you're so used to an entirely different way of thinking you're not going to be receptive at all."

As a result, students and academics who challenge the zeitgeist are stigmatised by their colleagues and university administrations.

One academic tells of a marker recommending a fail grade to a student thesis critical of postmodernist interpretations of terrorism. "Having read parts of his thesis I am certain that it did not deserve a fail," the academic says. "The only reason that I can think of for the examiner seeking to fail his thesis is ideologically based animus against his argument."

An Australian psychology academic was investigated by his university for setting an assignment that surveyed students on gender differences with regards to jealously. "The underlying theory is evolutionary — jealousy is linked to biological sex and males and females respond differently," the lecturer tells me.

A student accused the academic of "transphobia" in a pejorative Facebook post and complained to the university. The administrators spent months investigating, the lecturer was required to attend hours of meetings, and the dean of the school monitored lectures, ostensibly to make the student feel "safe".

Social psychology literature has established that men respond more strongly to sexual infidelity, and women more strongly to emotional infidelity. The survey — which included "male", "female" and "prefer not to say" options — was designed for students to test this theory and write up the results. The academic was never given a written complaint or formally cleared of wrongdoing and almost left his job because of the inquisition.

"I find myself having to be extremely careful, having a real anxiety about going into lectures and classes, and am very fearful of saying something that students find offensive," the academic says. "That affects my teaching, it makes me feel uncomfortable, it makes it difficult to think and present freely and clearly."

There have been many cases of censorship across Australian campuses. Last year, Monash University and the University of Sydney capitulated to demands for course content censorship — including a quiz and a map — by nationalistic Chinese international students. The University of Western Australia cancelled a contract to host "sceptical environmentalist" Bjorn Lomborg's Australian Consensus Centre, and no Australian university was willing to host it.

The monoculture has institutional backing through university policies and censorship.

My Free Speech on Campus Audit 2017, which analysed more than 165 policies and actions at Australia's 42 universities, found that four in five universities had policies or had taken action that was hostile to free speech.

University policies prevent "insulting" and "unwelcome" comments, "offensive" language and, in some cases, "sarcasm" and "hurt feelings". Some policies tell students and academics they are "expected" to value "social justice", a progressive political notion. These misguided policies make it difficult to explore controversial ideas without fear of reprisal.

Florian Ploeckl, a senior lecturer in economics at the University of Adelaide, says many academics bite their tongue on controversial topics. "If working on these topics is essentially futile, why should we make ourselves into targets for Twitter mobs and social media crusades?"

Ploeckl warns that academics instead are ceding the space to "activists with their fundamentalist convictions" who do not approach topics scientifically. "Funding is easier and more plentiful if you pick the right topic, publishing is easier if you don't rock the boat and life in the department is easier if you see the world in the same way your colleagues do," he says.

David Baker, a lecturer in history at Macquarie University, says while most academics are open to diverse viewpoints, "there is a small group of academics, whose behaviour can only be described as sinister, who are in the business of brainwashing their students and who will try to harm the careers of colleagues they deem heretical to their ideology ... Grades can be devastated, careers can be cut short and there is very little one can do about it."

The lack of viewpoint diversity ultimately has an effect on the quality of public discourse. "Universities and academics are uncritically accepting some theories, teaching them to students, and they are finding their way into society, influencing businesses and political debate," says Hardy Hulley, a finance senior lecturer at University of Technology Sydney who identifies as "pretty liberal".

The late Stephen Hawking once warned: "The greatest enemy of knowledge is not ignorance, it's the illusion of knowledge." Our ability to expose errors and discover truths is hampered by lack of free and open discussion.

There are reasons to be optimistic. The existence of Heterodox Academy indicates a willingness by some to challenge the orthodoxy. "I joined Heterodox because I wanted to pull myself away from my echo chamber and consider more diverse viewpoints," says Lydia Hayward, a psychology researcher at the University of NSW.

In the US, some institutions are staking their reputation on being open to debate.

The University of Chicago has declared that "it is not the proper role of the university to attempt to shield individuals from ideas and opinions they find unwelcome, disagreeable or even deeply offensive". Thirty-five US universities have adopted this statement.

Federal Education and Training Minister Simon Birmingham, in response to the concerns raised by Heterodox Academy members, has stressed the importance of views being challenged.

"Any university that limits constructive debate doesn't just do themselves a huge disservice, they let down the Australian public and taxpayers who chip in most of their university revenue," he tells me. "University leaders who aren't fostering debate on campus need to remember that the autonomy they are granted comes with the responsibility to understand the social licence taxpayers give them to operate."

They claim that the 2018-19 Budget will cut taxes. To most people, this would mean the amount of tax they pay next year will be less than what they pay this year. Yet, the government's own Budget figures show that taxes are rising rapidly year after year after year.

They claim that the 2018-19 Budget will cut taxes. To most people, this would mean the amount of tax they pay next year will be less than what they pay this year. Yet, the government's own Budget figures show that taxes are rising rapidly year after year after year. We are talking about private farmers who decide to develop their own privately held land. It isn't the government's land. And it surely isn't the Wilderness Society's land. Government bureaucrats and green groups have no business telling farmers what they can and cannot do on their private land.

We are talking about private farmers who decide to develop their own privately held land. It isn't the government's land. And it surely isn't the Wilderness Society's land. Government bureaucrats and green groups have no business telling farmers what they can and cannot do on their private land. Considering that Peter enrolled at James Cook University as an undergraduate back in 1978, he has been associated with that one university for forty years.

Considering that Peter enrolled at James Cook University as an undergraduate back in 1978, he has been associated with that one university for forty years.

The

The

Beyond these issues there's the question that as yet advocates for gender diversity have been unwilling to answer.

Beyond these issues there's the question that as yet advocates for gender diversity have been unwilling to answer. In 2006 Larry Summers was forced to quit as president of Harvard University when he suggested there were

In 2006 Larry Summers was forced to quit as president of Harvard University when he suggested there were  Which is exactly what the Australian Human Rights Commission contemplated last month when it claimed there was a "dismal" lack of cultural diversity among government and corporate leaders. It found

Which is exactly what the Australian Human Rights Commission contemplated last month when it claimed there was a "dismal" lack of cultural diversity among government and corporate leaders. It found  There's the proposal to raise the top threshold of the 32.5 per cent tax bracket from $87,000 to $90,000, which will stave off bracket creep for one or two years.

There's the proposal to raise the top threshold of the 32.5 per cent tax bracket from $87,000 to $90,000, which will stave off bracket creep for one or two years. The second hefty change is to eliminate the 37 per cent tax bracket from 2024-25. This would constitute the most substantial change to the income tax system for years. And it would mean that by 2024-25, around 94 per cent of taxpayers would face a top marginal tax rate of 32.5 per cent or less compared with 63 per cent if the system was unchanged.

The second hefty change is to eliminate the 37 per cent tax bracket from 2024-25. This would constitute the most substantial change to the income tax system for years. And it would mean that by 2024-25, around 94 per cent of taxpayers would face a top marginal tax rate of 32.5 per cent or less compared with 63 per cent if the system was unchanged. The aim of the ban, which was announced in the budget with other measures to tackle the "black economy", is to prevent money laundering and tax cheats. These are genuine goals. However, there is nothing inherently immoral or harmful about cash. The government is punishing the vast majority who do nothing wrong in an ill-fated attempt to prevent a small number of people acting illegally.

The aim of the ban, which was announced in the budget with other measures to tackle the "black economy", is to prevent money laundering and tax cheats. These are genuine goals. However, there is nothing inherently immoral or harmful about cash. The government is punishing the vast majority who do nothing wrong in an ill-fated attempt to prevent a small number of people acting illegally. Judging by the howls of outrage echoing through twitter it seems that the Turnbull government has destroyed our democracy, if not Australian civilisation itself. But no. The Turnbull government has frozen ABC operational funding for three years. That translates to a "funding cut" of some $83 million.

Judging by the howls of outrage echoing through twitter it seems that the Turnbull government has destroyed our democracy, if not Australian civilisation itself. But no. The Turnbull government has frozen ABC operational funding for three years. That translates to a "funding cut" of some $83 million. This was the fifth budget of the Coalition government and may very well prove the last before the Australian people hand power to Bill Shorten and Labor. This provides an opportune time to answer — what have they achieved?

This was the fifth budget of the Coalition government and may very well prove the last before the Australian people hand power to Bill Shorten and Labor. This provides an opportune time to answer — what have they achieved? Promised tax cuts in Tuesday night's Budget won't match expectations, and a Coalition government — which, after almost five years in office, should be renowned for getting government out of our lives — will have overseen further growth in government expenditure and debt.

Promised tax cuts in Tuesday night's Budget won't match expectations, and a Coalition government — which, after almost five years in office, should be renowned for getting government out of our lives — will have overseen further growth in government expenditure and debt. Marx treated people cruelly, was two-faced, and used racial slurs. In a 1862 letter, Marx described an opponent as a "

Marx treated people cruelly, was two-faced, and used racial slurs. In a 1862 letter, Marx described an opponent as a " Politicians hold press conferences telling the banks the prices they should charge for their products. Under the so-called "Banking and Executive Accountability Regime", a government-appointed committee (the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority) decides who the banks can employ and how much they're paid. The structure of the financial sector is decided by the government, and banks are of course prevented by the government from going broke.

Politicians hold press conferences telling the banks the prices they should charge for their products. Under the so-called "Banking and Executive Accountability Regime", a government-appointed committee (the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority) decides who the banks can employ and how much they're paid. The structure of the financial sector is decided by the government, and banks are of course prevented by the government from going broke. The responsibility of the directors of the CBA is to obey the law. And any law, regulation, or rule which the government expects a citizen to abide by, whether as a pedestrian crossing the street or as a CEO of a $100 billion bank, must be clear and comprehensible.

The responsibility of the directors of the CBA is to obey the law. And any law, regulation, or rule which the government expects a citizen to abide by, whether as a pedestrian crossing the street or as a CEO of a $100 billion bank, must be clear and comprehensible. One of the more compelling examples provided was that well-known Australian wine producer Brown Brothers was moving part of its operations to Tasmania — to a cooler climate. That is what journalist Michael Brissenden said:

One of the more compelling examples provided was that well-known Australian wine producer Brown Brothers was moving part of its operations to Tasmania — to a cooler climate. That is what journalist Michael Brissenden said: