A court case this week in front of three judges of the Federal Court was a further stage in Peter Ridd's fight for freedom of speech on climate change. The case, James Cook University v Peter Vincent Ridd, has enormous significance for the future of Australia's universities and scientific institutions.

Ridd's case is a dramatic illustration of the free speech crisis in Australian universities, not least around matters as politically and emotionally charged as climate change. It will determine, in effect, whether universities have the ability to censor opinions that threaten their sources of funding. It is one of the most important cases for intellectual freedom in the history of Australian jurisprudence.

Ridd's case is a dramatic illustration of the free speech crisis in Australian universities, not least around matters as politically and emotionally charged as climate change. It will determine, in effect, whether universities have the ability to censor opinions that threaten their sources of funding. It is one of the most important cases for intellectual freedom in the history of Australian jurisprudence.

The Ridd case has resonated around Australia — and has attracted significant attention worldwide — for good reason. It confirms what many people have suspected for a long time: Australia's universities are no longer institutions encouraging the rigorous exercise of intellectual freedom and the scientific method in pursuit of truth. Instead, they are now corporatist bureaucracies that rigidly enforce an unquestioning orthodoxy, and are capable of hounding out anyone who strays outside their rigid groupthink.

JCU is attempting to severely limit the intellectual freedom of a professor working at the university to question the quality of scientific research conducted by other academics at the institution. In other words, JCU is trying to curtail a critical function that goes to the core mission of universities: to engage in free intellectual inquiry via free and open, if often robust, debate. It is an absurd but inevitable consequence of universities seeking taxpayer-funded research grants, not truth.

Worse still, it is taxpayers who are funding JCU's court case. Following my Freedom of Information request, the university was forced to reveal that up until July last year, it had already spent $630,000 in legal fees. It would be safe to assume that university's legal costs would have at least doubled since that time. The barrister who JCU employed in the Federal Court this week was Bret Walker SC, one of Australia's most eminent lawyers. Barristers of his standing can command fees of $20,000 to $30,000 a day. And all of this is happening at the same time as the vice-chancellor of the university, Sandra Harding — who earns at least $975,000 a year — complains about the impact of government funding cuts.

While Australian taxpayers are funding the university's efforts to shut down freedom of speech, Ridd's legal costs are paid for by him, his wife and voluntary donations from the public. As yet, neither the federal nor the Queensland Education Minister has publicly commented on whether JCU is appropriately spending taxpayers' money and, so far, both have refused to intervene in the case.

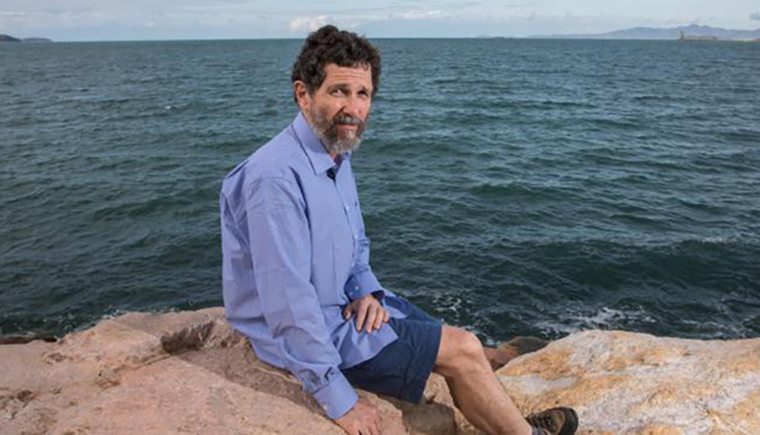

Ridd describes himself as a "luke-warmist". "I think carbon dioxide will have a small effect on the Earth's temperature," he told a podcast recently. "But it won't be dangerous." He has been studying the Great Barrier Reef since the early 1980s and was even, at one point, president of his local chapter of the Wildlife Preservation Society.

But Ridd is sceptical about the conventional wisdom that the Great Barrier Reef is dying because of climate change. "I don't think the reef is in any particular trouble at all," he says. "In fact, I think it's probably one of the best protected ecosystems in the world and virtually pristine."

The problems Ridd's views cause for JCU are obvious. The university claims to be a leading institution when it comes to reef science, and has several joint ventures with taxpayer-funded bodies such as the Australian Research Council Centre for Excellence in Coral Reef Studies.

Ridd challenged his sacking in the Federal Circuit Court on the basis that the university's enterprise agreement (which determined his employment conditions) specifically guaranteed his right to "pursue critical and open inquiry", "express unpopular or controversial views", and even "express opinions about the operations of JCU and higher education policy more generally". In September last year, Ridd won his case as the court found he had been unlawfully sacked and he was awarded $1.2m in damages and compensation for lost earnings.

The case in the Federal Court this week was an appeal by JCU against that decision. At issue was whether the intellectual freedom clauses in the enterprise agreement covering JCU staff protected his criticism of quality assurance issues in reef science at the university. The university alleges that in going public with his concerns that organisations such as the ARC Centre "cannot be trusted" on reef science, Ridd committed several breaches of the university's staff code of conduct, with its vague, faintly Orwellian requirements to act "collegiately", and to "uphold the integrity and good reputation of the university".

In other words, even though the enterprise agreement specifically declared that staff had the right to intellectual freedom, it was for the university to determine the limits of what that freedom actually permitted. If it is accepted, it will be the death knell of free intellectual inquiry in Australia's universities. As Ridd's barrister, Stuart Wood QC, said to the Federal Court: "If you can't say that certain science cannot be trusted because it is 'discourteous' and 'not collegial', then you cannot call out scientific misconduct and fraud. It's not just the end of academic freedom, it's the end of the scientific method. At that point, JCU ceases to be a university and becomes a public relations outfit."

An academic who doesn't have the ability to challenge the research findings of their colleagues because those questions threaten the university's funding doesn't have intellectual freedom. And if academics know they could get sacked, as Ridd was, for asking uncomfortable questions, they will stop asking uncomfortable questions.

Academics should of course be open to criticism — particularly for some of their more outlandish conclusions — but as a matter of public policy it is vital that universities be places where bad ideas can be expressed as well as good ones. The difference between the former and the latter should be resolved by free and open debate, not opaque "disciplinary processes". We may not like what university professors say, but a strong university sector requires that we defend to the death their right to say it.

It is up to the Federal Court now to decide exactly how far universities can go to censor and sack their staff. But in Ridd, James Cook University has one professor who will not go quietly.

Red tape imposes an enormous burden, reducing economic output to the tune of $176 billion across Australian each year. While this is a dangerous handbrake on prosperity, it is also a serious moral issue. By preventing people from starting new businesses, innovating new products and creating opportunities for themselves and their families, red tape stifles the aspirational spirit that drives so many West Australians.

Red tape imposes an enormous burden, reducing economic output to the tune of $176 billion across Australian each year. While this is a dangerous handbrake on prosperity, it is also a serious moral issue. By preventing people from starting new businesses, innovating new products and creating opportunities for themselves and their families, red tape stifles the aspirational spirit that drives so many West Australians. The unemployment rate for April jumped to 6.2 per cent, up from 5.2 per cent in March. The increase was substantially lower than many forecasts. Following the release of the unemployment rate Treasurer Josh Frydenberg stated the lower than expected rate "reflects the success of the JobKeeper program".

The unemployment rate for April jumped to 6.2 per cent, up from 5.2 per cent in March. The increase was substantially lower than many forecasts. Following the release of the unemployment rate Treasurer Josh Frydenberg stated the lower than expected rate "reflects the success of the JobKeeper program". It might have been that the minister was absent when the Morrison government was busy selecting the members of its National COVID-19 Coordination Commission.

It might have been that the minister was absent when the Morrison government was busy selecting the members of its National COVID-19 Coordination Commission. To be fair, things could be worse. The federal government has committed to borrow an eye-watering sum of money and is subsidising businesses to maintain employees on their payroll. Right now a lot of people are still receiving an income, despite not actually working.

To be fair, things could be worse. The federal government has committed to borrow an eye-watering sum of money and is subsidising businesses to maintain employees on their payroll. Right now a lot of people are still receiving an income, despite not actually working. The Student Services and Amenities Fee is a compulsory upfront payment of up to $308 introduced by the Gillard government in 2011. This repackaged form of compulsory student unionism, where fees are set by the university but with a large portion going to the union or guild, has resulted in a conflict of interest that has left domestic students without a voice at a crucial time.

The Student Services and Amenities Fee is a compulsory upfront payment of up to $308 introduced by the Gillard government in 2011. This repackaged form of compulsory student unionism, where fees are set by the university but with a large portion going to the union or guild, has resulted in a conflict of interest that has left domestic students without a voice at a crucial time. Total Australian debt has already blown out to $618 billion, up $50 billion since December. The increase in borrowing has been a result of a $11.3 billion collapse of government revenue compared to the pre-COVID-19 forecasting. Total debt is set to spiral over the coming years as the government's spending commitments in response to COVID-19 get underway and as government revenue is further damaged by the ramifications of the lockdown and reduced investment.

Total Australian debt has already blown out to $618 billion, up $50 billion since December. The increase in borrowing has been a result of a $11.3 billion collapse of government revenue compared to the pre-COVID-19 forecasting. Total debt is set to spiral over the coming years as the government's spending commitments in response to COVID-19 get underway and as government revenue is further damaged by the ramifications of the lockdown and reduced investment. The University of Queensland's predicament did not begin with the news that it was employing one of the country's top legal firms to pursue a member of its own student body, nor will it end there.

The University of Queensland's predicament did not begin with the news that it was employing one of the country's top legal firms to pursue a member of its own student body, nor will it end there. Australians have been told that life will not return to normal until a sufficient number of people comply with the government request to download and activate on their mobile phones a programme, known as COVIDSafe, launched earlier this month. When a person tests positive to the virus, the data the app collects can be used to track, trace, and isolate the outbreak. Users are required to give consent to the data collection and it is opt-in.

Australians have been told that life will not return to normal until a sufficient number of people comply with the government request to download and activate on their mobile phones a programme, known as COVIDSafe, launched earlier this month. When a person tests positive to the virus, the data the app collects can be used to track, trace, and isolate the outbreak. Users are required to give consent to the data collection and it is opt-in. The former Liberal leader John Hewson is right when he says the national cabinet has for the moment at least, suspended the "point-scoring and blame-shifting" of traditional politics. Everyone on the national cabinet likes to pretend that, regardless of their politics, they agree with each other and are united during this national crisis.

The former Liberal leader John Hewson is right when he says the national cabinet has for the moment at least, suspended the "point-scoring and blame-shifting" of traditional politics. Everyone on the national cabinet likes to pretend that, regardless of their politics, they agree with each other and are united during this national crisis. And now, with a single tweet, we know exactly the kind of "expert" Andrews is listening to, and it explains a lot.

And now, with a single tweet, we know exactly the kind of "expert" Andrews is listening to, and it explains a lot.