An address to the Compaq Computer Australia

Opportunities in Excellence luncheon series,

22 February 2000

IAN PENMAN, COMPAQ COMPUTER AUSTRALIA

I'm Ian Penman, Managing Director of Compaq Computer Australia. It's my pleasure to welcome you to the eleventh Compaq Opportunities in Excellence luncheon.

Before introducing our guest speaker I would like to quickly recap on the progress of our seminar series. Our first Opportunities in Excellence luncheon was held late in 1995, and we're really pleased that a lot of you have been coming back many times to these sessions.

Today Compaq is the second largest computer company in the world, the largest supplier of PCs, servers and storage solutions, and the second largest global supplier of notebooks. Compaq is also one of the leading professional services organisations. We provide end-to-end, full life cycle services that cover systems design and implementation, management, and the support of networks, applications and systems.

The Canberra market is critical to our future success, so we are eager to hear your questions and thoughts over lunch today on how Compaq is serving this market, and how we can help you achieve your business goals in the future.

In our Opportunities in Excellence series, we always strive to deliver topics that are relevant and speakers who can entertain as well as inform. The feedback we have received over the years indicates that we have been meeting those objectives and today's topic and speaker is certainly no exception. Compaq's role for today's lunch, and the entire series, has always been that of a facilitator. We are non-partisan, providing the forum for independent experts to provide their views on key issues confronting Australian industry and government.

One such issue is the development of regional Australia which has been top of mind in government circles lately, particularly following the Prime Minister's "Listening Tour" of regional areas. Australia is moving quickly from the industrial age to the information age and we must address how we manage this change in ways that give our regional communities their best opportunities for a secure future.

In October 1999, the Honorable John Anderson called the Regional Australia Summit because he said he is worried that regional Australia is not sufficiently prepared for the information age. The Summit participants discussed areas of importance including access to telecommunications services and the rollout of necessary infrastructure, e-commerce and teleworking opportunities, the delivery of Local, State and Federal Government services, the ability to attract new industries to regional areas and the role government plays in this, and the retention of skills in the regional areas.

At the end of the Summit, the participants defined a vision for regional Australia, which is: "a strong and resilient regional Australia which has the resources, recognition and skills to play an equal role in building Australia's future and is able to turn uncertainty and change into opportunity and prosperity."

To share his expert opinion on the future of regional Australia, I would like to welcome Mr Richard Wood, Councillor on Commerce Queensland's South-West Region Council. Mr Wood will discuss many of the issues covered in the Summit and outline the growth pattern for development in industries such as call centres, value added processing, transactional centres, and community banking. He will also cover Australia's opportunities to increase its economic competitiveness through the development of its regional areas, including expansion into Asian markets.

Mr Wood is widely recognised as an expert on this topic, having written numerous publications and research papers about the development of regional Australia. He has been in his current role with Commerce Queensland since 1997. Educated in Toowoomba, Mr Wood commenced his career establishing his own financial management practice in March 1996. With an entrepreneurial spirit and vision as Managing Partner, he has developed and guided his business to where it is today, providing solutions for Accountants, Banks and Business globally, delivering leading risk management, relationship and portfolio management and monitoring capabilities.

Unlike traditional accountants, Mr Wood does not position himself as external to his clients' businesses. Where possible, he becomes a part of the client -- knowing as much about their operations and corporate and marketing challenges as possible. This provides a sound foundation from which to develop financial and accountancy strategies which are tailored to meet their individual requirements. Importantly, it also allows him to identify business opportunities for his clients on a progressive basis, and combat any commercial threats before they take effect.

Ladies and gentlemen, please join me in welcoming today's speaker, Richard Wood.

MR RICHARD WOOD

I would like to thank Ian Penman and Compaq Computer Australia for giving me the chance to address one of the major issues facing Australia into the 21st Century.

We live in exciting and strange times. The world is experiencing growth in opportunities and wealth not seen since the latter part of the 19th century. Yet there is a deep angst in the community, particularly in rural Australia. Why? In term of microeconomic outcomes, the reforms put in place over the last 15 years has paid off in a big way.

The Australian economy is humming. According to Paul Krugman -- one of the world's most respected economists -- Australia is a "miracle economy". It has withstood the Asian crisis without missing a beat. It is into its eighth year of economic growth. Since 1996, GDP growth, adjusted for population and inflation, has been near the top of the pack in the OECD. Productivity is growing at over 2.5% -- more than double the rate achieved over the 1970s and 1980s. In short, we are experiencing growth in the overall economy and in productivity not seen in Australia since the 1950s.

Wealth has also grown steadily for most of the last decade, reaching a growth rate of 10% last year. Wealth is also being distributed quite evenly in relative terms. Australia now leads the world in share ownership and is at the top of the pack in home ownership. Inflation -- which in the past has ravaged people on fixed incomes -- is down and under control. Moreover, the intensity of competition is up across the economy.

A U.S. magazine, Site Location -- a bible for people seeking to relocate footloose investment projects around the world -- rates the business climate in Australia as the best in the world after the U.S. Electricity, telecommunications and gas prices are down, as are rail and transport charges.

Despite the noise from the "social justice industry", the distribution of income -- adjusted for transfer payments, taxes and housing subsidies -- has narrowed over the last fifteen years and poverty has declined. These outcomes have not been a fluke; they are the explicit result of ongoing reform implemented by governments of both parties over fifteen years at both a State and Federal level.

These improvements also have been driven by major global changes. We are currently going through not one, but two revolutions; a bio-technology revolution and a communications revolution. These are creating huge opportunities, but also huge uncertainty. They offer growth and wealth but also impose change and adjustment. Of course, nations can opt out, but the cost of doing so is higher than ever.

Despite the benefits of reform, despite the good overall economic outlook and despite the improved distribution of wealth and income, we are experiencing a backlash against reform. Of course the existence of a backlash per se is not surprising. Some people are inherently risk averse. They don't like change. But more importantly, they don't like the rate nor breadth of change. Institutions that were bred under the old circumstances are having their reason for existence challenged. People who had advantages in the old system are losing them.

What is surprising is both the severity of the backlash and where it is coming from -- the bush and regional Australia. After all, was it not the National Farmers Federation with their fighting fund who led the push for reform? Weren't many of the reforms specifically aimed at improving the exporting sector which is located overwhelmingly in the bush?

This is not just an academic issue. The backlash is threatening good government. Governments of all persuasions are chasing their tails to mollify rural constituents. This is not only slowing reform but also encouraging politicians to waste scarce funds by building pyramids rather then productive assets. Importantly, it is also feeding a culture of dependence in the bush.

While it is true that by almost any indicators, sections of the bush are falling behind socially and economically, the bush is far from a basket case -- though you would not reach this conclusion by reading the press.

These imperatives gave rise to the National Regional Summit held last October in Canberra. Although the Summit didn't try to lay out a strategy, it did attempt to address "the vision thing" and did a good job at it. First, the Summit concluded that, "a strong, resilient regional Australia has the resources, recognition and skills to play an important role". What this means is that the bush is not a basket case and it has a role to play in the growth of Australia.

Secondly, and this is the important part, the Summit concluded that, "the task is to enable the bush to turn uncertainty and change into an opportunity and prosperity". In other words, the Summit concluded that there is no going back on reform and that an openness to the global economy is essential to the bush. Good stuff from Canberra!

Although the Regional Summit didn't lay out a plan, its various speakers did map out the essentials of a successful regional development strategy -- a strategy which I fully endorse.

First, they made it clear that to be a successful strategy it had to emanate from the local community. Strategies handed down from on high -- from Canberra or Sydney or Melbourne or Perth -- do not work.

Second, local commitment to growth is the key. Communities that are against growth or attempt to lock themselves away from the market, not surprisingly, do not grow and provide few opportunities for young and old, working and dependent people.

Third, the task is to understand the weaknesses and strengths of the local community; to understand the forces driving change; and to take advantage of opportunities and minimise the threats.

Fourth, the strategy must start with what one has rather than with a clean slate. For many rural communities this means building on the existing agriculture, mining or resource base.

Fifth, communities must embrace new opportunities and technologies.

Sixth, government has a major role in providing key enabling infrastructure. Importantly the infrastructure of today is fundamentally different from the infrastructure of the past -- trains and roads are not the priority they were. Today's infrastructure priorities lie with telecommunications and biotechnology.

What I would like to do now is go through some of the drivers of change and then go on to look at some challenges and some opportunities.

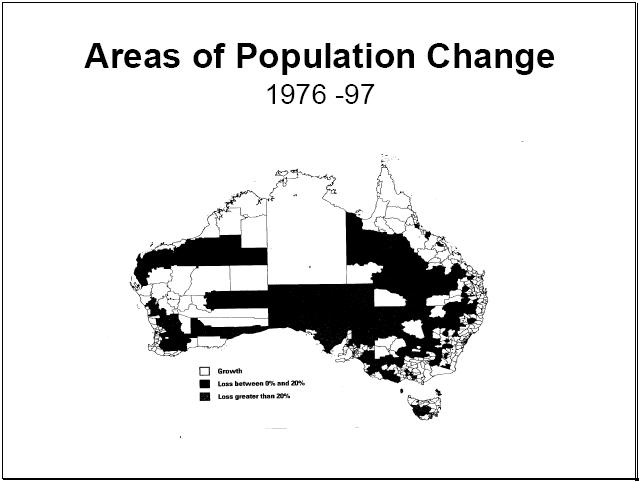

There are four defining population trends. First, people are looking for a slower pace of life down at the beach -- they are drifting to the coast. Over the last ten years, 1.3 million people have moved to the northern New South Wales coast. A similar trend is discernible in Victoria and Western Australia. Retirement decisions and the search for a "Seachange" drive much of this.

The second trend is the expansion of sponge cities. People are leaving the smaller inland country towns in droves and moving to regional centres like Dubbo, Bendigo and Bunbury. These regional centres are growing rapidly and at the expense of their surrounding areas. This trend has been in evidence for some time but has accelerated in recent years.

Third, there are regional places of opportunity. There are a range of places that are growing very rapidly. The classic examples are Karratha in northwest W.A. and Rutherglen on the Murray in Victoria. Karratha is booming thanks to its abundant gas and oil reserves. Rutherglen is booming thanks to wine and tourism.

Fourth, the growth of "global cities". Leading industries are increasingly becoming concentrated in specific locations. For example, if you are in the Internet start-up business you at least have to have a foothold in Silicon Valley. If you are in the fashion business it is Paris or maybe Hong Kong. In the motion picture business, it's Los Angeles or perhaps Bombay. As these global cities grow, benefits flow from them to their hinterlands. Although Australia has no dominant global cities, its capital cities do have potential to play a vital niche role in global markets, which, if achieved, will offer huge benefits for the bush.

Sponge cities are set to grow, and the fundamental reason is better roads, better cars and consumer choice. Why are people abandoning local businesses in inland country towns? The reason is simply: cars are better, roads are better, and there is more choice for consumers in the regional cities. In short, rural community members are voting with their feet and going to areas of greater choice.

Another thing causing the depopulation of smaller towns is the aging of the farming population. The average age of farmer today is 52 years. Their parents have already retired -- largely to the coast or city -- and many farmers will shortly join them. The youth are also leaving rural Australia, mainly for the bright lights and universities in the capital cities. Many do not return to regional Australia. Those that do go overwhelmingly to sponge cities.

What these trends mean is that many small inland towns are going to continue to decline, particularly small rural towns based on broad acre agriculture and forestry. The enemy is not globalisation, economic rationalism or Canberra but rather rural people voting with their feet to shop elsewhere. More importantly, we haven't seen anything yet. The Internet is going to offer a huge increase in shopping options and place enormous competitive pressure on local shops in rural areas.

Another factor driving change in rural Australia is the changing structure of world demand. The world is changing, not by some grand plan, but rather by people pursuing their preferences through the market place. We are getting wealthier. We are spending more on services rather than goods. Accordingly, the agricultural sector as a whole is declining steadily as a share of GDP, while specialist high price crops are booming, as is the demand for value-added agricultural products.

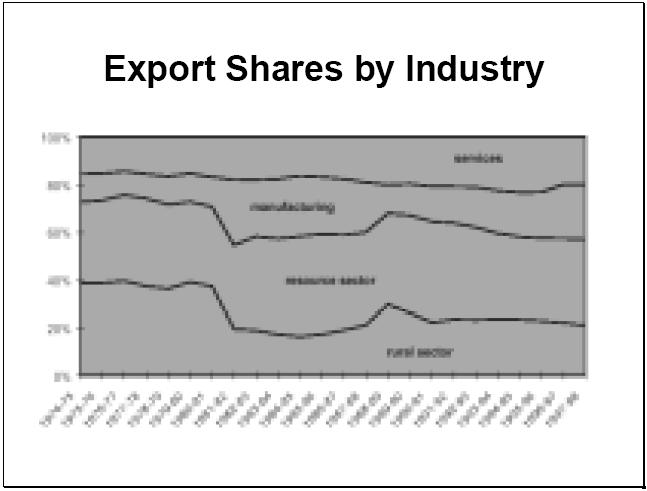

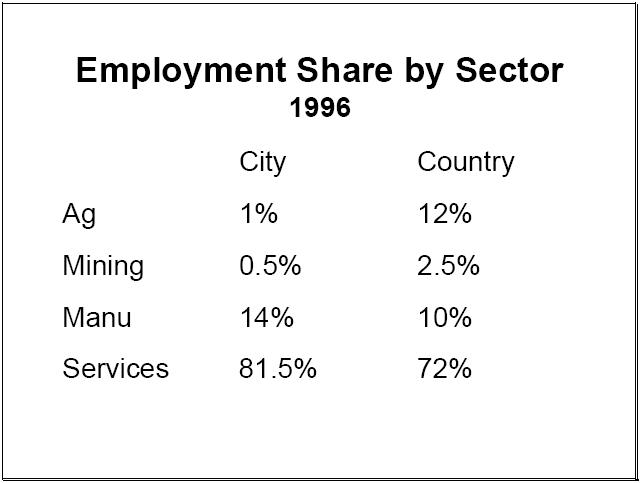

Although the primary industries -- agriculture, mining and forestry -- are declining as a share of GDP, they remain vitally important to the non-metropolitan regions. The agriculture and resource sectors still account for about 58% of exports. They still account for the bulk of businesses and economic activity in rural Australia. These sectors account for 14.5% of the workforce in rural areas. More importantly, many of the jobs in the services and manufacturing sector are driven by the agriculture and mining sector.

This brings us to the real cause of rural Australia's problem -- its dependence on declining industries. As these charts show, the decline in employment in rural Australia has been driven primarily by the decline in agriculture and, to some extent, mining.

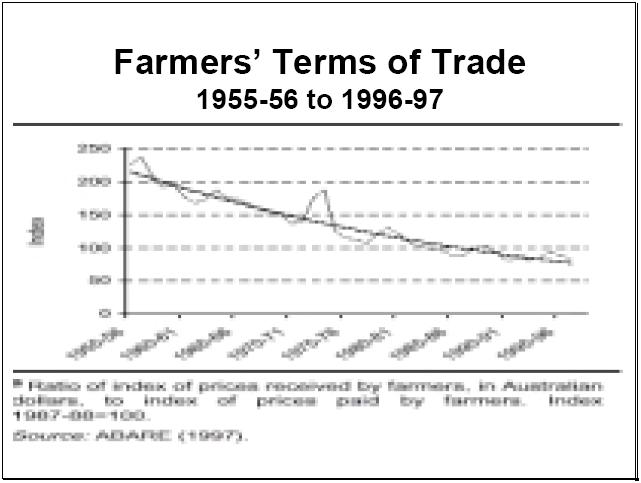

What is driving the decline in the primary sector? Simply put, the terms of trade have been declining continually for decades. Since most agriculture and mining commodities are necessarily exported, Australian governments have no real capacity to do like the Europeans and Americans and cuddle the bush in masses of protection and assistance. As a result, Australian farmers and miners have, and must, continue to be internationally competitive by improving productivity, being innovative and keeping costs in check.

People have been hoping and praying for a new resources boom for decades, hoping that the world would run short of resources which in turn would yield huge windfall gains to Australia. This has not happened and probably will not happen in our lifetime.

We have been trying to convince the Americans, Europeans and Japanese for years to jettison the madness of agricultural protection. We must continue to do so, as nothing could be better for the bush than lower trade barriers for agricultural products -- it offers the potential of injecting $2 billion a year into the income of Australian farmers. Nonetheless we can not rely on trade reform being a reality soon.

Therefore we must focus on improving productivity, lowering cost and adjusting to markets. Which means more change in the bush.

The question is why is the bush in revolt? The reason is that the bush is basically made up of two groups -- one made up of people and groups involved in the international competitive agricultural and mining sectors, and the other made up of people working in protected and inefficient government businesses and services. The groups are, as it turns out, mutually exclusive. The primary sector cannot flourish nor any longer afford a bloated, inefficient set of public trading enterprise.

For most of this century governments have used their trading arms as rural job creation schemes. As a result of these policies, public trading enterprises accounted for 40% of service employment in rural areas.

For years this was sustained by the huge wealth of the land. As a result of the sustained decline in the terms of trade, the agriculture and mining sectors could no longer carry the burden of over-manned and slack support industries. Changes were needed if the primary sector was to remain viable and these changes have been put into place over the last fifteen years.

The result was large reductions in the workforce in trading enterprises, particularly in rural Australia. Over the last decade 33%, or 100,000 people, have been cut from the workforce of these organisations. Roughly half of those were in rural and regional Australia.

There are some positives to the reform. First, it has given the primary sector greater capacity to compete and, if not to grow, to remain viable. The reforms have also aided the growth of private sector service providers. Much of the decline in public sector employment -- even in the bush -- has been offset by growth in the private sector. Some of the workforce was simply shifted over in full to the private sector via privatisation. The reforms have also given rise to a new range of private sector providers which have filled niches opened up by deregulation and economic change.

For the nation as a whole, the growth in the private sector workforce has more than compensated for the reduction in the public sector work force in the telecommunications, rail, road, and electricity industries. While there is hard data on the impact on the bush, my guess is that the growth in private sector service jobs in the old utility industries has not been enough to compensate for cuts in the public sector.

It isn't only the public trade enterprises, but also the banks and other private infrastructure providers that are going through radical change. Up until the mid-1980s, banks were highly protected from competition, pricing decisions and the need to invest in technology. As a result, banks maintained highly inefficient practices such as keeping a large under-utilised network of rural branches. It was a happy cartel. In the 1980s the cartel began to crack and the banks -- staffed more by bureaucrats than businessmen -- reacted with stupidity that nearly sent two of the four major banks into bankruptcy.

As a result, they entered the 1990s in a real hole -- with a huge load of non-performing loans, layers of inefficient practices and an excessive investment in bricks and mortar. They also were hit by a technological revolution and a wave of new and agile competitors. They had to change or they would be driven out of business. They had no fat to live off, they were losing customers in droves and their customers where demanding new electronic services.

The cost imperative of adopting new technology for the banks was overwhelming. Transactions at ABMs cost 66% less than the same transaction at branches. Telephone and EFTPOS are even cheaper, while Internet banking is 99% cheaper than branch transactions. Even so, the push toward electronic banking did not come primarily from the cost side. Customers were increasingly demanding and adopting new forms of transactions. Over 70% of bank transactions are now done outside branches via electronic routes. The competition from new providers is fierce. In the past people joined a bank for life and let the bank handle all of their financial transactions. Now loyalty is gone. People spread their business across a range of providers. Importantly, the home loan -- formerly the most lucrative business for banks -- is increasingly going to Aussie Home Loans and other home loan providers who offer one service with no bricks and mortar at all.

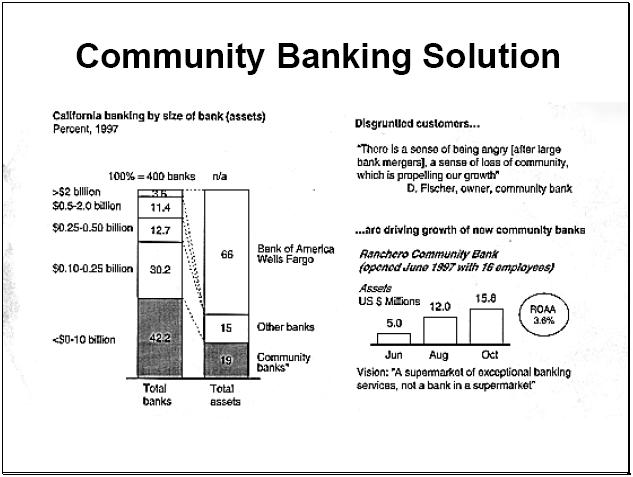

Banks are starting to react. What's driving this? Profits, yes. Banks have responsibilities to their shareholders. But it's largely market driven. Why is there a decline in banks' branches in small regional centres? People are doing their shopping in the sponge cities and not in the rural areas -- and they are getting their money through EFTPOS rather than over the counter.

Simply put, the decline in rural bank branches is being driven by rural people. And this is not going to change. It is not going to be solved by declaring laws that force banks to continue to operate branches that nobody wants.

There is a new paradigm out there. Things have changed. There are new industries and opportunities and new policy priorities that have to be addressed. First, the consumer is king. In the end the ability or willingness of governments to limit technology and consumer choice is greatly limited.

Second, this is the age of the subcontractor; not just in government, not just in big firms, but throughout business activity both here and abroad. Organisations are increasingly focusing on what they do best and contracting out other things to other people. This is creating huge opportunities buy also threats to rural and urban life.

During the 1950s, Australia had what is best called a "workfare" state. The Government focused on providing jobs through public trade enterprises and nation-building facilities. The policy was to ensure people had work -- workfare -- rather than providing passive assistance -- welfare.

In the 1970s things changed for a variety of reasons. Whitlam created the welfare state. The "workfare" state -- providing jobs through public trading enterprises -- began to cost too much in terms of taxpayer-funded subsidies and excessive charges on exporting industries. Given limits to peoples' willingness to pay taxes, governments were forced to make a choice between workfare and welfare and they choose the latter.

This not only supported the move to improve the efficiency of trading enterprises but also led governments to focus less on institutions and more on individuals and less on inputs and more on outputs. As a result, when people leave rural areas, governments tend to ensure that funding for services such as schools, hospitals and aged care follow them.

A priority of government is to fill the gaps left by the private sector and the reform process. This is particularly important for the bush. One area of concern is the gap in "network facilities" such as banking, the post, air transport and telecommunications.

One way to address the problem is to have regional community transaction centres that pool the various networks systems and providers.

Another important approach for regional Australia is in the provision of tele-medicine and tele-education services to overcome the loss of hospitals and schools. One of the biggest problems in the bush is that GPs and teachers don't want to stay there. It's not that the income is too low, it's just that they don't have the high-tech facility or colleagues to draw upon that they have in the cities. Tele-medicine and tele-education facilities can help overcome these problems.

One potential solution to the decline in face-to-face contact is Bank Bendigo's innovative community banking solution. Bank Bendigo has responded to community concern about the closure of bank branches by asking communities to put their actions and money where their mouths are. It goes to communities that have lost bank branches and says, "We will provide you good, sound banking services through branches, if you take equity in the branch, patronise the bank and get a large number of customers to come on board". It's a good community solution to a problem, and it is a model that is driven by commercial sense and by technology. It's also been very profitable for Bank Bendigo.

The reforms and the changes in the bush have produced many success stories, most impressively in the food industry. Few other industries have offered so much and delivered so little. Study after study has found it to be an industry of huge potential, but also an industry that has failed to meet its potential. It has been diagnosed as being too inward looking, fragmented, dominated by cooperatives, and having poor international linkages. Well, banking, like many other industries, has been put through the wringer by the reform process and some sections, at least, are coming through in very good shape. The are growing rapidly -- areas such as in the Goulburn Valley in Victoria -- and are creating burgeoning, sustainable growth.

Another success story is the wine industry. Australia now exports over $1 billion in wine per year and has three of the top ten wine export companies in the world -- which is impressive given that Europe still accounts for 70% of the world's wine trade and Australia for less than 5%. Australia also has the second highest average value of wine sold on the world market -- after New Zealand.

High-tech cotton and the tree farming business are also Australian success stories. Australia is one of the few countries in the world that is actually increasing its standing stock of forest -- both native and otherwise.

Biotechnology offers great potential to rural Australia. It offers the potential for lower costs and lower pesticides and herbicides use. It offers more salt and drought resistant varieties. It offers the potential for new crops and new crop rotation systems. This potential is under threat from what I call the NIMPYs (Not in My Plate Yet) -- people who fear the technology on religious grounds or for competitive or social reasons. Their campaign has gained the attention of the public and has the potential to stop the new technology altogether.

The Howard Government is doing an extremely good job at attempting to counter the scare and deal with the fear associated with the technology as well as promoting the development of the technology.

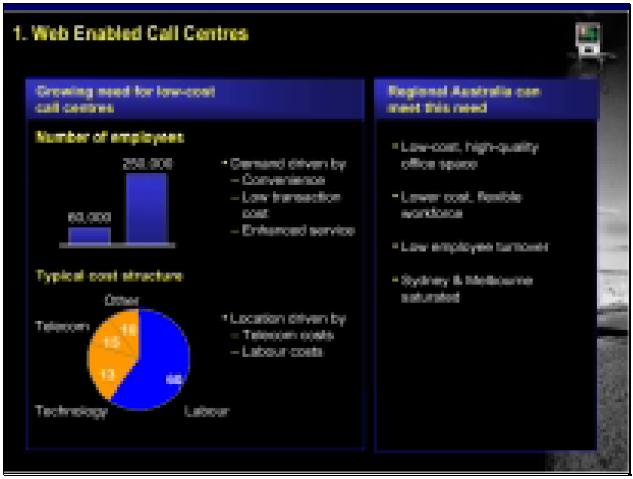

Another area that has grown dramatically in recent years, thanks to reform, is the call centre industry. Two things are surprising about this industry: its size and its potential.

Call centres are creatures of change, driven by advances in communication technology, globalisation and privatisation. New technology offers companies scope to make huge savings in a wide range of communications with customers. It offers the scope to centralise communication thereby reaping economies of scale and the benefit of specialisation. It also offers the potential to accumulate a wider range of information about customers and have greater knowledge about their demands.

Globalisation and technology have allowed the task of communication to be separated not only from head office but also from the restriction of geography and nation-states. This has given rise to the new global call centre business. For example, centres located in New Zealand are currently providing customer communication services to electricity firms in California.

The call centre industry has been greatly assisted by reform and competition in the telecommunications industry. As the price of phone calls has declined and the number of competitors increased, the scope for communication aggregators have grown. This clearly has been the case in Australia.

Up until 1996, the call centre sector in Australia was small and limited to a few large firms. In 1996, the Government reduced tariffs on imported equipment, allowed a greater range of suppliers to enter the market, allowed the entry of new telecommunications firms. As a result, the call centre industry has grown more than ten-fold in three years.

Privatisation has also given call centres a large boost, as it has brought in new ways of operating and new ideas and standards of service.

The call centre industry is, not surprisingly, particularly strong in North America. In 1998, the U.S. had 70,000 call centres with a total workforce of 2.5 million workers -- which is almost 2% of the total U.S. workforce -- and revenues of $24 billion. The experts forecast that the number of centres in the U.S. will grow to over 100,000 by 2003, while employment will push 3% of the workforce, and revenues will approach nearly $50 billion.

In Australia, the experts estimate around 250,000 people currently work in call centres -- up from just 60,000 three years ago. If true, this means that more people work in call centres than in the banking sector altogether. Put differently, for every job lost in retail banking over the last decade, call centres have created nearly four new jobs.

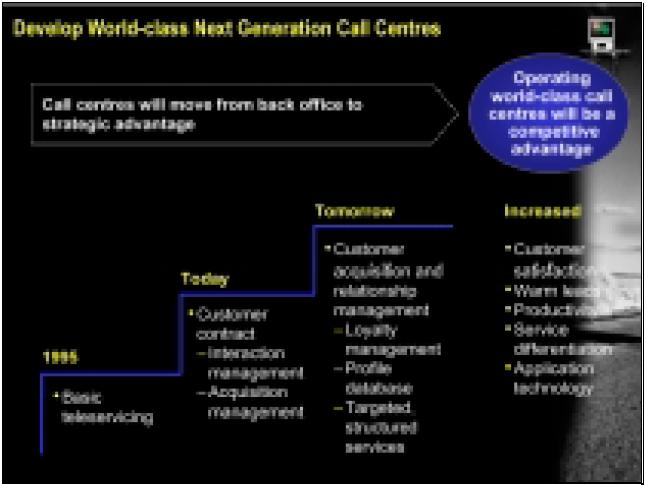

Contrary to earlier concerns, the advent of the Internet is strengthening rather than undermining the growth of call centres. Traditional call centres are based on voice communication via phones. As people increasingly shift away from phones to the Internet -- as is already happening -- it was feared that call centres would lose their comparative advantage. To date however, the growth of e-mail has increased the demand for call centres -- not as phone communication centres but as centres for processing of e-mail and other Internet communications and transactions.

In short, the Internet is creating a huge increase in communication flow that needs to be managed and call centres are filling this niche.

Call centres first started around 1985, providing a basic answering and bill paying service. They have now advanced to providing a customer advisory and research service. The next trend is expected to be into customer database management and profiling. The centres have, like most industries, moved steadily up the valued-added chain, adding new, more advanced services, demanding higher skills and paying higher wages.

Importantly for rural Australia, call centres are a global business in which rural regional are highly competitive. Call centres need good communication facilities, large amounts of good quality office space, articulate English-speaking people and people able to pick up technological skills -- attributes that many rural centres in Australia have in abundance.

Many such centres are attempting to exploit this advantage and some are doing so quite successfully. For example, Bendigo, which is a major hub on the trunkline between Melbourne and Sydney, has more than 200 large call centres and a number of others on the drawing board.

Of course, the call centre industry is a highly competitive, global industry. No region has an absolute advantage. Moreover, the competition from overseas is increasing. One of the main sources of competition is India. India has 300,000 employees in the call centre industry, and this is expected to swell to more than one million in a few years time. India, with its low cost but highly skilled software and engineering work force, is particular strong in advanced call centres providing advisory services.

One of the disappointments of the Regional Australia Summit, and much of the debate about infrastructure in rural Australia, is that it has focused on old technology -- trains and roads. These are important but not as important as telecommunications infrastructure. The fact is, most of rural Australia is already well served by a high quality road network. Although the train system in Australia leaves much to be desired and is in need of improvement, it is not central to the renewal of rural Australia.

In contrast, telecommunications is the key to the renewal process. It is the key to the new growth industries. It is vital to keeping small towns in touch with the world. It is crucial to the competitiveness of sponge cities. It is crucial to improving or even maintaining community and network services to rural Australia. It is also an industry going through massive change and innovation demanding new investment and experimentation.

Telecommunications, therefore, must be the key focus of rural renewal. And there is a long way to go both in terms of quality and services to improve the services in the bush.

But we must jettison the approach of the past where the bush was treated as a welfare case, supplied and subsidised by a benevolent monopolist under the direction of governments. This did not work in the past and certainly will not work in the future. Telstra is a private firm struggling to remain viable in a highly competitive global industry. It no longer has the incentives or capacity to be the best provider of services or technology to all of rural Australia.

The answer lies in using competition -- which has worked so well for the cities -- to the advantage of the bush. Thus, instead of having Telstra provide and fund telecommunications services to the bush under its community service obligation -- valued by the Government at $280 million per year -- the provision of community service obligations should be put out to competitive tender. This should be done not only as a means of getting more services per subsidy dollar but to get new ideas and technology into the bush.

Optus and AAPT have made it clear they could provide better and cheaper service to the bush than is currently provided by Telstra. Moreover, new rural specialisation could spring up as it has in the U.S. Given that Telstra's rural infrastructure is old and fully amortised, the subsidied rates are unlikely to be adequate for funding a new infrastructure. As such, an additional source of funding will be required. The obvious source is Telstra -- that is, the sale of its remaining 51%. Once Telstra loses its last remaining monopoly -- services in rural Australia -- government ownership is simply unnecessary.

To sum up, the backlash from the bush is, to a large extent, a problem of the bush. Sections of rural Australia lead the fight for reform and they have been one of the main beneficiaries of reform. Other sections of rural Australia have been most adversely affected by reform. This tension needs to be in a large part resolved within rural communities.

Second, economic development must be based on what we currently have and what opportunities are currently available -- and that means focusing on improving the prospects of the primary sector.

Third, we have to do away with the idea that the bush is buggered. There are many examples of success stories and there are many opportunities created by reform.

Finally, we need to focus our infrastructure efforts not on the technologies of this last century but rather those of the 21st Century -- telecommunications and biotechnology. We also need to use the institutional frameworks of today -- global firms, competing locally -- rather than the institutions of yesterday -- government monopolies acting slowing and poorly.

Thank you very much.

QUESTIONS

If you are a sponge city, you might be okay, but if you are in a non-sponge town, what is going to drive your survival in the future?

Sponge cities are basically driving the population and activity from the adjacent areas. If you live in a small town that isn't on the coast and doesn't have a mine next to it, well, you are going to shrink to a large extent, mainly because people themselves in those communities are driving the sponge city. So what do you do? You make the best of your facilities, you make sure the towns are kept in touch with a variety of areas that I've explained and also, most importantly, you focus on developing the competitive advantages that lie in that area, whether it be tourism or value added processing. The real question is do you stop this process of services flowing with the demand? No, I think not.

What is this emphasis on call centres? To me, call centres seem to be verging on sweat shops, and that is why they are being drawn to places like India where labour is cheap.

First of all, work is work. It is valuable particularly in a dying town and in a sponge city. Second, call centres are for low-income workers. In the U.S. there are major changes in the fundamental nature of call centres -- instead of just answering services, they are into data processing and greater knowledge of the customer base, and wage rates are above the average. That is, the average wage rate in American call centres is US$32,000 for a full time employee, and that is higher than the average weekly wage of a full-time employed male worker.

We are getting changes in growth in the nature of call centres. India is not only a call centre haven, but also much of Microsoft Window 2000 code was written in India. Back to the point, call centres are the processing plants of the future, and as they did with other processing plants, they will add technology and improve productivity and wage rates. But they are entry-level jobs, and that is exactly what is required in the bush if you look at the demographics. A job is a job.

How do you entice companies to move or expand their operations into regional areas?

One of the issues that I didn't deal with was regional development policies -- how do you entice firms to locations and the issue of subsidies. My firm belief after 20 years is that subsidies are best. If you don't have your fundamentals right in certain areas, they won't go, or they will go for a while until the subsidy dries up and then they will move off.

You also have to draw on the competitive advantage of the areas. Goulburn Valley did not have to entice firms to its area or provide subsidies of any sorts because it had competitive advantages. Subsidies can be a benefit and a necessity, but they are also a pollution of the process. Take call centres -- one of the biggest problems in the Goulburn Valley is that state governments have poured their largesse -- millions and millions of dollars -- into bringing call centres into the area, otherwise they would have located in places like Bendigo and Ballarat. So regional assistance is a necessity.

One of the beneficial effects of the Regional Summit was that for too long we've looked at regional development as a top-down, government-led process -- a planning process of industrial development. But it isn't, it is basically a community driven, locally driven and organic process, and too often regional development processes stop that from happening.

IAN PENMAN, COMPAQ COMPUTER AUSTRALIA

I would like to thank Richard for certainly giving us a real insight into some of the issues, some of the opportunities and some of the imperatives for regional development within Australia.

On behalf of Compaq, I would like to thank all of you for taking the time to attend today. I hope you found it as interesting and as fun as I did, and of course we would be delighted with any feedback you can give us from today's session. I hope to see you all again at our next in the series of Compaq Opportunities in Excellence luncheons here in Canberra.