An Address to the Institute for the Service Professions Symposium,

Edith Cowan University, 10 March 2000

ECONOMIC LIBERALISM AND THE COMMUNITY SERVICE SECTOR

THE DEMISE OF SOCIALISM AND RISE OF INDIVIDUALISM

For much of the 20th century, collectivism was the prevailing ideology in Australia and around the world. Capitalism was believed to be fatally undermined by inefficiencies, instability, market failure and unacceptable inequalities. Individuals were believed to be poorly informed, open to exploitation and in need of guidance.

The solution was thought to lie in governments managing the commanding heights of the economy, regulating the allocation and distribution of goods and services, and playing an ever-increasing role in the redistribution of income and wealth. Accordingly, the size of government grew steadily in Australia from 10 per cent of GDP in 1901 to about 40 per cent of GDP in 1982 and by larger amounts in other developed countries.

About twenty years ago the worm began to turn. Reliance on collectivism and big government began to wane and reliance on individualism and markets began to rise.

As Lord Robert Skidelsky, the author of The World After Communism, put it:

"... governments in developed and developing countries alike have been privatising their public sectors and shredding instruments of intervention and control. The aim of economic reform is remarkably similar everywhere: a market economy based on private ownership with accountable government limited to a relatively few functions."

The process started before the fall of communism, arguably in the world's two major opposites -- the US and China.

In the late 1970s, the Carter Administration began the process of deregulating the transport and communication industries -- two industries which proved to be crucial to driving technological change. A little later, but in the same decade, Deng Tsu Peng [sp]officially abandoned communism and put China on the capitalist road, thereby beginning the true cultural revolution. In the early 1980s, Thatcher in the UK, Reagan in the USA, Lange/Douglas in New Zealand and later Hawke/Keating in Australia began to transform their economies and governments. Later in the decade Mr Gorbachev introduced perestroika and, in so doing, announced the failure of communism as a political and economic ideal. Many Asian countries, who had either abandoned or avoided altogether the collectivist economic development nostrum, began to flourish.

In 1989, with the fall of the wall, the Russian empire collapsed and thirty per cent of the world's population began the difficult process of creating a market economy and a liberal democratic order.

The pace of change picked up and spread throughout the world during the 1990s. Continental Europe began to move slowly but perceptibly away from many of its cherished collective policies. This process was often lead by ostensibly socialist governments. Indeed Europe has lead in the privatisation stakes in terms of volume and value through the 1990s. With the creation of the European Union, barriers to trade, investment, immigration, location of business and competition are being removed across all the member states. This process is spreading throughout eastern Europe as countries jockey for the right to enter the EU.

Most south and central American countries are in the process of abandoning their collectivist past for more liberal economic policies.

During the 1990s, the British Labour Party officially abandoned its commitment to socialism and adopted the "the third way", which in essence adopts and advances most of Lady Thatcher's policies and philosophies, albeit at a slower and politically attuned pace. President Clinton has done the same in the US.

Even the Fabian Society -- the intellectual flag bearer of socialism in the English-speaking world during most of the 20th century -- has joined the revolution. It now is a supporter of market systems and privatisation.

Not surprisingly, this has not been a politically popular process. It does, after all, transfer control and resources from the political sphere to the private sphere. People who rely on political control have lost influence. It also undermines the way of life and the ideology of the many who believe and work in "the collective".

That fact that it has happened, that it has often been put into place by avowed socialists, and has shown no signs of being reversed or even slowing, indicates that it has some powerful forces behind it and is not a temporary aberration on the path to the ideal socialist state.

WHY THE SEACHANGE?

1. Failure and Performance

The main force for change has been the failure of big government coupled with the success of markets.

State-owned enterprises around the world have consistently failed to produce the goods. They characteristically provide poor and costly services; are inefficient and lack innovation. They are prone to overmanning and "staff capture" and often have an arrogant attitude towards consumers.

Government industry planning and controls have often undermined rather than enhanced competitiveness and tend too often to pick and support declining industries rather than expanding ones.

Active macro-economic management proved to aggravate rather than abate instability. It also lead to high inflation, rising debt and rising unemployment.

Government regulation of labour markets tended to drive a wedge between workers and employers as well as between workers and productivity growth. The result has been low productivity, counterproductive work practices and low employment growth, particularly for low-skilled workers.

Government-provided welfare services tend to encourage dependency, to lack innovativeness and to focus on the symptoms rather than the solutions.

In contrast, economic freedom -- individual choice, competitive markets, secure property rights, free trade -- not only outperformed big government but proved to be far less prone to failure, inefficiencies and inequity than was commonly predicted.

In other words, market failure -- though real -- was not as prevalent as earlier assumed while government failure proved to be endemic.

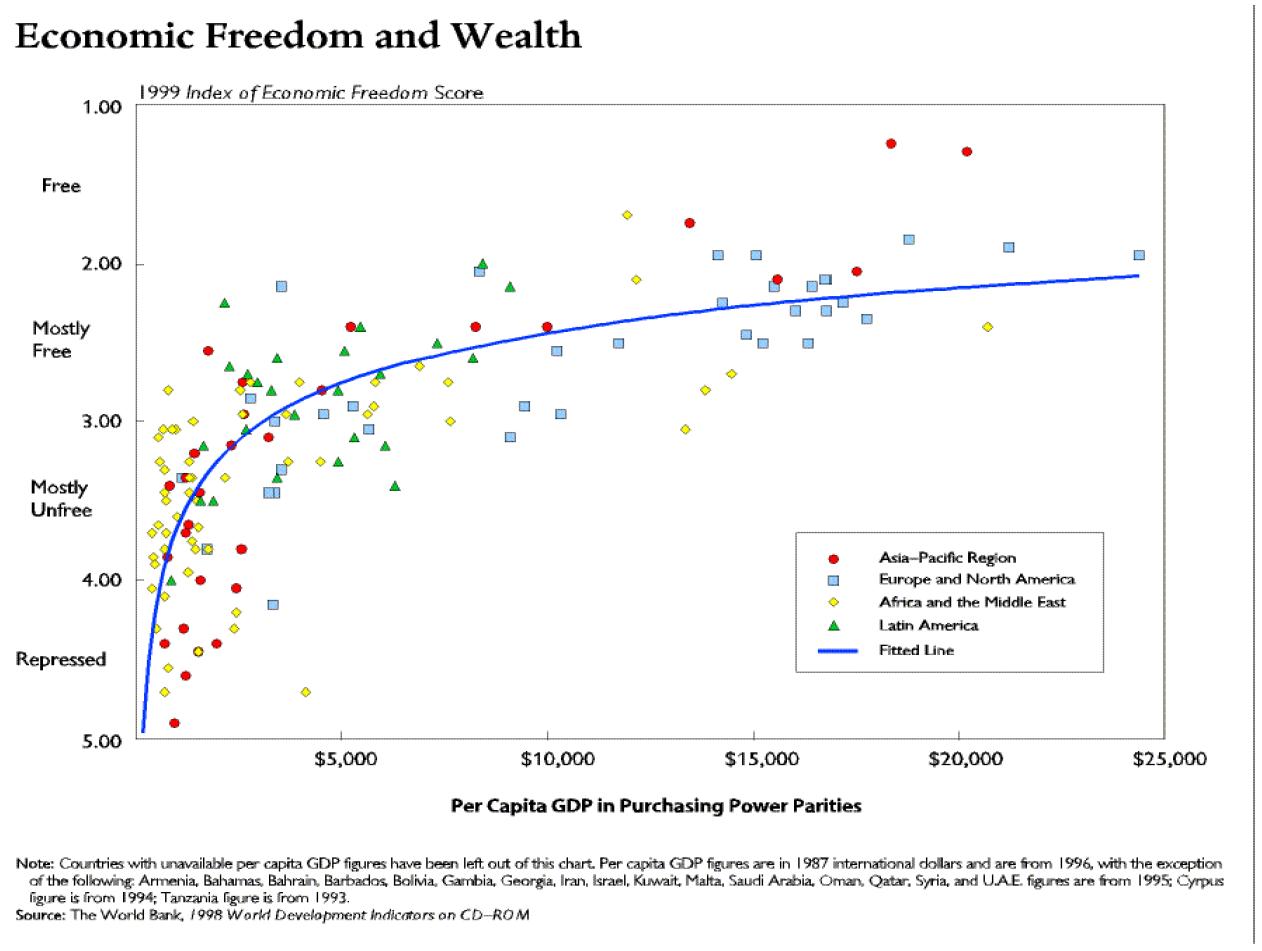

The proof was in the pudding. As illustrated in Figure 1, countries which adopted a more open and market-oriented policies -- called economic free policies -- achieved much higher rates of growth. Economic freedom is also associated with greater equality of income rather then less.

Figure 1

Of course it took time for the evidence to come through and be accepted by a very sceptical public and by hostile elites.

The abject failure of communism, provided many with enough evidence to make at least tentative steps to greater economic freedom.

The performance of the US, the UK and importantly Australia during the 1990s relative to the more collectivist European nations, and relative to their own performance in the 1970s and 1980s, is enough to convince even the most sceptical.

2. Globalisation

Globalisation, which is driven in large part by a combination of technological change and the adoption of liberal market policies, has undermined governments' ability to maintain collectivist policies.

Global capital markets tend to hunt out, expose and reward success and punish poor performance. They also tend to prefer competitive markets to political decision-making and controls.

Markets have an uncanny ability to circumvent barriers erected by governments. They also accentuate the cost of government failure.

Of course governments still have the ability to remain in control and restrict the market. In short, they can take the North Korean option. But this is a Hobson's choice as the costs are too high for any democracy to withstand for ever.

3. Consumer sovereignty.

Consumers are increasing demanding choice and control and, in so doing, are driving the shift from the collective to individual choice.

Affluence, technology and markets have given consumers immense choice and control of their own life decisions. They have also greatly reduced governments' ability to limit choice.

The level of service, choice and control provided in the market sphere has also increased the standards of performance expected of government.

Even though many babyboomers are in their hearts collectivists, they are in their actions a most individualist generation and have both driven and relished this new found freedom. They, more than anyone else, have driven the rise of individualism. Generation X appear to be less collectivist and more comfortable with markets than their parents but just as desirous of choice and control.

4. Limit to tax.

Around the developed world, taxes have more than trebled as a share of income over the last fifty years and are approaching their political and economic limits.

In some nations such as France, Sweden and the Netherlands, taxes now absorb around 60 per cent of GDP. Even in the low-tax developed nations, including Australia, taxes consume over 34 per cent of GDP, which is more than double the level in place in the 1960s.

Although only in the US has there been a "tax revolt", most nations are struggling to squeeze more out of their taxpayers. Although tax shares have not declined over the 1990s in many countries, the rate of increase has slowed dramatically and in some countries stopped altogether.

Australia is no exception. Although many collectivists look with hope at the large gap in taxing levels between Australian and, say, Sweden, the fact is that Australian's have a lower tolerance for tax -- one much lower than the Europeans.

For proof one needs only observe the GST debate. The GST, which is essential to retaining current tax levels and levels of government spending into the future, is deeply unpopular and could only be introduced after three tries and with a huge reduction in personal income and other taxes.

This politically-imposed limit on the size of government has been, and will remain, a key driver in the use of markets and greater individual responsibility. It also means that efficiency and equity are closely intertwined.

5. Growth of Welfare.

Up to early 1970s Australia had what is aptly called a "workfare state". The main focus of government was to manage and plan the development of the economy. Its major instruments were tariffs, regulations and business enterprises. Taxes were low and welfare spending was amongst the lowest in the OECD.

Full employment was achieved by a combination of rapid accumulation of capital -- much as the Asian countries did during the 1980s and 990s -- a buoyant world economy, massive wealth in the resource sectors and large labour-absorbing business enterprises.

In essence, the government offered people workfare, or jobs, rather than welfare.

This process was upset during the 1970s by two related forces. First, as outlined above, the collectivist state began to fail: growth slowed, productivity fell, competitiveness declined and unemployment grew.

During this period the Whitlam Government introduced the welfare state, with a massive increase in the range and level of entitlements.

As shown in Figure 2 as result of the increase in demand from the slowing economy and the expansion in entitlements, social transfers expanded from about 10 per cent of GDP in 1972 to 17 per cent in 1979.

Growth of this magnitude was clearly unsustainable. The Hawke/Keating Government correctly tackled the main cause, that is the failure of the workfare state. It also began to tackle the growth of entitlements through targeting, user charges and greater efficiency in the delivery of services.

Despite these reforms, welfare transfers continued to grow over the next two decades -- driven primary by health and welfare transfers.

Given the aging of the population, the underlying demand for health and welfare transfers will continue to grow and it will continue to drive the need for rationing and efficiency in these and other areas.

6. Decline in trust.

Another factor -- seldom discussed but nonetheless real -- that has driven the shift toward individualism is the decline in trust in institutions and authority.

Babyboomers may in their heart be collectivists but in their brains they are anarchists. They do not trust authority, institutions or power, particular those long-established. They have an affinity for direct action and people power.

As a result, politicians and political parties are on the nose around the world. Big is bad. Bureaucracies -- whether in the public or private sector -- are seen as dinosaurs.

As Ziggy Switkowski, CEO Telstra put it last week:

"Let's face it, it's not easy right now being a traditional institution, government organisation or business....we seem to be built on old-fashioned models, we seem to have legacies in terms of investments, obligations and historic processes that don't seem relevant to the modern age".

This mind-set not only undermines the power of the collective and government institutions but also augments the drive for greater individual control.

Importantly, it gave impetus to the rise in non-government organisations -- both as an alternative to government in terms of collective activity, but also as a provider of services.

In summary, the rise of individualism and markets is not just or even primarily driven by a bunch of ideological econocracts in Canberra as Professor Pusey and company would have you believe. It is being driven by a much more complex and powerful set of forces.

There are a number of other myths about the process of change and economic reform which need to be explored if you wants to understand the process.

MYTHS ABOUT ECONOMIC REFORM.

Myth # 1 Stopping reform is an option.

It is often claimed that economic reform should be slowed or stopped because people are tired of change.

While it is true that many people are tired of change, they also want the improvements in their lives that only come with change.

Much of the change is being driven by the demands of these very same individuals: by their demand for greater control and choice, their calls for better and more services, and by their distrust in institutions and bureaucracies.

Moreover, no government can control all changes or ensure that change occurs at some predetermined rate. Many of these factors are beyond the control of government. For instance, the aging of the population, with all of its demographic consequences and the communications revolution which is transforming all aspects of life, are effectively beyond the control of governments.

Myth # 2 Reformers have unlimited faith "in markets".

Economic reform does not involve slavish adherence to market forces. Competition, deregulation and privatisation are legitimate tools in the reform armoury, and they have yielded large benefits. But they are not ends in themselves and they are not relevant in all circumstances.

In reality, many limitations of the market are openly acknowledged by reformers. They understand the key role played by government in supporting markets. They also understand that the government must finance the provision of so-called public goods -- those goods that would be under-supplied by the market. The government also has an important role in maintaining a social safety net for those in genuine need. There is much to debate about the nature of that safety net -- about its level, whether assistance should be in the form of cash transfers or of specific services, and who should be eligible to receive them and how and by whom they should be delivered. But the need for a state safety net is accepted by most people.

Reformers are also aware that a market economy depends crucially on a wider civil society that is strong and supportive. Markets operate best when there is a culture of trust, honesty, respect for others, and good faith dealing. Such a culture cannot be created overnight by government. Where it is lacking, markets will be characterised by short-termism, fraud, fly-by-night operations and, at worst, gangster capitalism.

Ultimately and contrary to accepted wisdom, the strength of our civil society depends, not on government, but on decisions made by all of us as individuals, and as members of the groups to which we belong. A market economy must be built from the bottom up.

Myth #3 Microeconomic reform is bean counting

Governments are always being accused of penny-pinching by some interest groups, as well as being criticised for using taxpayers' money extravagantly. Experience suggests that the focus of attention should be less on the amounts spent and more on the performance of dysfunctional systems.

Many reforms within the public sector -- such as direct resourcing in schools or the separation of funding and provision in health -- are aimed at getting better value for the taxpayers' dollar.

Often good microeconomic reform has a positive impact on the government's budget, such as when subsidies to exporters were abolished. But sometimes it has had the opposite fiscal effect, as when tariffs have been cut. And it is easy to name existing statutes where the purpose of the legislators would be better served by an explicit subsidy than by regulation.

Usually the debates over microeconomic issues are not about limiting some total aggregate of money. More often they are about who is best placed to make decisions over how much money to spend.

None of this is to deny, of course, that the aggregate level of government spending is important. Government spending has an opportunity cost and there is a limit to people's' willingness to pay taxes.

Myth #4 Markets are without social conscience

One popular claim is that reform comes at the cost of social cohesion.

As Paul Kelly, International editor of The Australian said:

... the biggest and most dangerous myth in our current political dialogue -- [is] that economic efficiency leading to economic progress, and social inclusion leading to a more caring and tolerant society, are incompatible. This assumption has almost become an article of faith in some quarters. The slogan is entrenched -- if you believe in the market, you don't believe in society. It is damaging because it is false and its consequence is to weaken economic liberalism or social inclusion or both.

And it is hard to see how delivering higher incomes to people ranks as an exercise without social conscience. Permanently higher incomes are achieved only through increasing productivity, which is what economic reforms are mainly about. Higher incomes enable people to consume more of those goods and services that are important to them. Such goods and services obviously include health, education, the arts, environmental goods and all those other activities that opponents of reform typically claim are neglected under economic liberalisation.

Moreover, societies can't share what they don't produce. By generating higher levels of national income, reforms aimed at improving the productivity of the economy provide the wherewithal to fund the access and equity objectives of governments in education, health and other key services. We do not see world-class social services in poor, unproductive countries, no matter how "free" to the consumer those goods may be. Richer countries also typically have cleaner environments.

WHAT IS IN STORE FOR THE COMMUNITY SERVICES SECTOR?

In aggregate, at least, the structure of the sector will change little.

As shown in Figure 3, the delivery of services has already largely been privatised and contracted-out. Non-government organisations and for-profit organisations dominate the industry. Together they account for 93 per cent of organisations, 79 per cent of employees and 72 per cent of expenditure.

The role of government has already been carefully dissected. Clearly, it is focused on funding, purchasing, regulation and monitoring.

My hunch is that, in terms of further structural reform, the focus will be on contracting-out of the purchasing role. That is, the creation of a set of case managers or agents who are funded by government to advise, coordinate and purchase services on behalf of clients. Of course this is already being done in some areas such as employment services and it makes sense in other areas where needs change, are complex and change over time, and where there are gains to be had from coordination. Aged care -- including health and housing -- seems to be a logical target.

In terms of process, contracting, competition and accountability are already the norm in the sector. My hunch is that the focus of reform will continue to be one of improving existing processes, together with a shift in emphasis away from measuring and controlling input and processes to one of measuring and rewarding outcomes.

The main challenge lies with the role and functions of the NGO sector.

As shown in Figure 3, NGOs dominate in the provision of community services overall and, as shown in Figure 4, in most types of service. However, governments still provide the lion's share of funding and determine policy, and in my view will continue to do so into the future. As such, NGOs are increasingly become subcontractors to the state.

This has a couple of significant implications for the NGO sector and the community service sector as a whole.

First, it brings into question the independence and raison d'etre of NGOs. If NGOs get most of their funding from governments to provide services determined by the states, then they will lose their independence because NGOs have characteristically been established not just to provide a predetermined service but to make a difference, to "do it their way".

If all they are businesses, why should they retain a non-profit status?

Second, it brings into question the ability of NGOs to continue to mobilise society. Aside from their ingenuity, governments like to use NGOs because they are better at mobilising society, both in the form of volunteer labour and donations -- in short, they are cheaper. However, their ability to mobilise society is to a large extent derived from their ability to make a difference. If they are just getting paid to carry out the dictates of government, why volunteer? And if governments are their main paymaster and are driving the activities and policies of the NGOs, why give a donation?

In summary, I think the biggest challenge facing the community sector, aside from culturally accommodating the rise of individualism and decline of the collective, is the long-overdue re-evaluatation of the role of NGOs.

In short, the task will be to ensure that civil society does not get captured by government.