An Address to Housing Industry Association,

July 2005

THE HOUSE BUILDING INDUSTRY

Housing, as a good that is not internationally tradeable has its costs determined by the efficiency with which the supply of housing stock is made available to buyers and the demand for the product itself. Unlike tradeable goods housing is not subject to disciplines of import competition.

Prices therefore are determined by local or at best national supply and demand situations.

Prices will vary according to:- The pressure of demand on the existing stock which at any one time is unlikely to be able to be expanded by more than a few percent

- The cost of expanding supply which in turn depends on

- The efficiency of the supply industry

- The regulatory arrangements that might increase its costs

- The ability of the existing housing stock to be adapted and traded, itself a function of regulatory and taxation considerations of

In terms of efficiency of supply, Australia has the benefit of a house building industry that is low cost and readily adapts to provide consumers with the product they want. The industry is readily open to new competition and its main feature is cross-contracting among independent businessmen -- sparkies, brickies, plumbers, chippies -- freely contracting with each other. The Australian house building industry, with efficiency levels that are inferior to none in the world, operates in stark contrast to the union controlled construction sector which is pregnant with outdated and inflexible work practices.

HOUSING AFFORDABILITY IN AUSTRALIA

The Demographia International Housing Affordability Ratings examines about 80 different locations in North America, Australia and New Zealand. It arranges an affordability index base on the average price costs as a multiple of average earnings. All seven of Australia's major capital cities are placed in the top dozen least affordable cities.

This affordability spectrum is not purely a matter of income levels. In the US, Miami, where houses are unaffordable, is not a particularly high income city. On the other hand Dallas and St Louis are two relatively high income cities with highly affordable house prices.

Nor is it a matter solely of pressure on resources. Though cyclical price rises and falls occur in the industry, two of America's most affordable cities, Little Rock and Dallas are also seeing high urban growth. We saw a variation of that ourselves with the experience of South East Queensland during the mid-1990s. A Rapid increase in the demand for housing due to inter-state migration was accompanied by a supply response possibly due to the availability of land. The net result was a major jump in new housing activity with little pressure on prices either in the new or estalished housing markets, especially on the urban fringe.

Table 1: Least Affordable Cities

| Country | Least

Affordable

Cities | House

Price

($US) | Ratio to

Average

Household

Earnings | Smart

Growth

Policies |

| USA | Los Angeles | 649,450 | 10.1 | YES |

| Australia | Sydney | 505,000 | 8.8 | YES |

| USA | Honolulu | 460,000 | 8.1 | |

| USA | San Francisco | 646,800 | 7.9 | YES |

| USA | Miami | 281,400 | 7.3 | YES |

| USA | New York | 398,800 | 7.1 | |

| Australia | Melbourne | 373,800 | 6.9 | YES |

| Australia | Adelaide | 248,800 | 6.2 | YES |

| Australia | Hobart | 242,300 | 6.2 | YES |

| Australia | Brisbane | 300,000 | 6.0 | YES |

| NZ | Auckland | 352,000 | 5.9 | YES |

| USA | Las Vegas | 276,550 | 5.8 | |

| USA | Sacramento | 319,200 | 5.6 | YES |

| USA | Sarasota | 267,600 | 5.6 | |

| Australia | Canberra | 361,900 | 5.6 | YES |

| Australia | Perth | 255,700 | 5.4 | YES |

Table 2: Most Affordable Cities

| Country | Most

Affordable

Cities | House

Price

($US) | Ratio to

Average

Household

Earnings |

| USA | Dayton | 119,100 | 2.6 |

| USA | Allas | 140,650 | 2.6 |

| USA | Todeo | 115,400 | 2.6 |

| USA | Omaha | 33,650 | 2.5 |

| USA | Pittsburgh | 116,150 | 2.4 |

| USA | Tulsa | 114,550 | 2.4 |

| USA | Indianapolis | 127,200 | 2.4 |

| USA | Columbia | 120,700 | 2.4 |

| USA | Little Rock | 110,650 | 2.4 |

| USA | St. Louis | 132,400 | 2.4 |

| USA | Wichita | 106,250 | 2.2 |

| USA | Rochester | 110,000 | 2.2 |

| USA | Buffalo | 95,600 | 2.1 |

| USA | Syracuse | 98,700 | 2.1 |

| USA | Forth Wayne | 99,150 | 2.1 |

Clearly Australia is in a situation of high cost housing when measured against the US and Canada. How did this come about and has it always been with us?

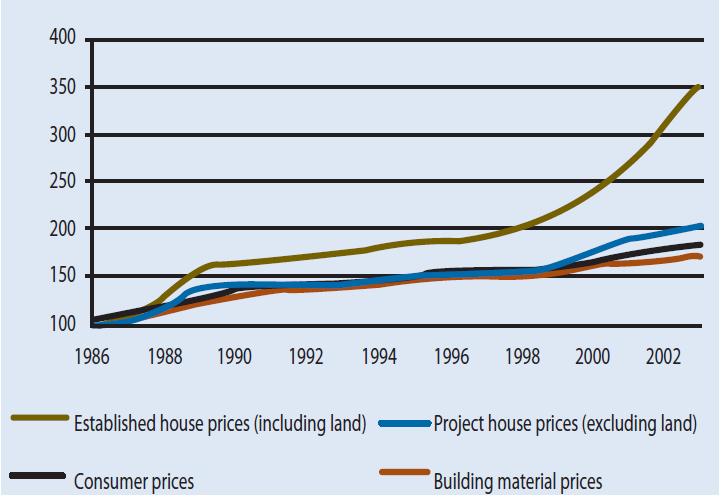

PC evidence of costs increases is best encapsulated in Figure 1 which was included in the First Home Ownership Inquiry Report.

Figure 1: Housing cost increases, 1986-2002

As the chart shows, house prices have outpaced inflation. In real fact new house/land package prices have doubled over the period with all of this increase due to the higher costs of land, taxes and development requirements.

The HIA has assembled as good a source of statistics as is available and the following will be familiar to many of you since it is taken from Rod Pearse's DR Dossetor lecture in June 2005.

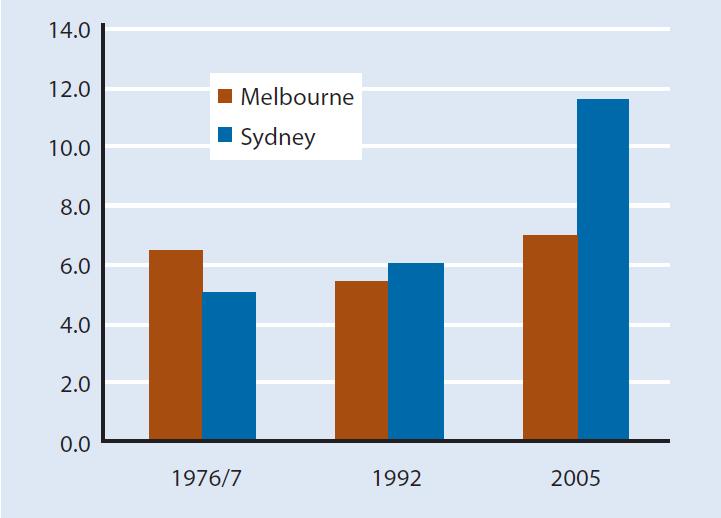

When we examine this data against real wage trends, the overall deterioration in affordability is not quite as serious, at least outside of Sydney. In gross wage terms an average new house in Melbourne requires seven years income which is a little higher than in 1976/7 and 1992. In the case of Sydney a strong increase in prices is clear -- house prices have gone from five and a half times annual earnings to 11 and a half times. (The numbers differ from those estimated by Demographia largely because of different house prices).

In the case of Sydney, had land prices and associated land development charges been kept to the real level that they were in 1976/7, instead of a house land package of $565,000, we would now be seeing prices of under $400,000. Had prices for land and its development increased along the lines of the consumer price index, as they did in the lower cost US cities, both Melbourne and Sydney would now be far more affordable.

Placed in simple terms, the key aspects of the increased costs are the scarcity value created by urban planning and the imposts heaped on developers by government regulations. Over the past thirty years the share of land in the housing package costs in Sydney has increased from 32 per cent to 62 per cent and in Adelaide from 16 per cent to 44 per cent, with other states showing comparable increases.

The urban planning system is the chief culprit. For Melbourne the 2030 Strategy has essentially replaced zoning as the determinant of costs. Soon after this was introduced land inside the Urban Growth Boundary, say around Whittlesea, could be seen to be selling at some $600,000 per hectare with comparable land outside the area selling at $150-200,000 per hectare. At 15 houses per hectare this escalates the basic land cost from $10-13000 up to $40,000. And the value outside of the residentially zoned area already had a premium due to speculation that the area would eventually be zoned residential. Indeed, the value of the land without such an expectation would be likely to be of the order of $4,000 per hectare.

On top of this are mandatory charges for development. Many of these would be required in any event but some are clearly extortionate.

In Australia, the cost of building has increased slightly ahead of general inflation over the past two years, though the main culprit in escalating new home prices has been the price of land, there is a disturbing trend towards increased regulations adding to costs.

One builder provided evidence that the increased documentation required for new house building in NSW cost an additional $9,958 per dwelling over the past few years. The HIA estimated that the regulatory "tax" on new subdivisions in western Sydney was $60,000. Though some of this is arguably for infrastructure directly contributing to the value of the subdivision, much of it is for social infrastructure like "affordable housing contributions", local community facilities, public transport contributions and the employment of community liaison officers.

Table 3: Most Affordable Cities

Table 4: Typical New House and Land Prices by Capital City, 1976 to 2005

| 1976-77 | 1992 | 2005 |

| Sydney |

| House | $49,010 | $189,800 | $565,000 |

| Land | 32% | 44% | 62% |

| Melbourne |

| House | $63,200 | $169,000 | $340,000 |

| Land | 24% | 24% | 38% |

| Brisbane |

| House | $46,280 | $164,690 | $362,000 |

| Land | 21% | 39% | 41% |

| Adelaide |

| House | $46,280 | $125,970 | $272,000 |

| Land | 21% | 26% | 44% |

Over recent years we have seen considerable "economic" deregulation (tariffs, airlines, telecoms, energy etc.) However, this has been accompanied by a vast increase in "social" regulation. This covers requirements for occupational health, safety, energy savings, assistance to people with handicaps, environmental conservation and so on. Perhaps the best economy wide means of measuring this is in terms of new regulations enacted each year. Those for the Commonwealth and for Victoria are illustrated in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2: Pages of Victorian Legislation passed 1959-2003

Figure 3: Pages of Commonwelath Legislation passed 1901-2001

THE REGULATORY BURDEN

The housing industry is not unique in facing a mounting onslaught of cost impositions, many of which are responses to heart-tugging issues facing our fellow citizens, some of which are designed to press forward energy and water saving measures and still others may be designed purely to increase government revenues. The net effect is a considerable burden on the home owner -- especially the new home owner who, not presently owning a home, is likely to be less forceful in articulating any objections.

One outcome, in addition to lower new home building activity per se, must be a reduction in levels of home ownership as a result of the increased cost impositions. As well as distorting consumer choice, this might have a wider adverse community impact so far as home ownership is a great force for social stability and the creation of an aspirational society that has done much to transform living standards over recent times.

We face a confusing picture with regard to the housing industry's regulatory future at the present juncture. On the one hand we have evidence of deregulatory moves with the Productivity Commission report on Reform of Building Regulation and forceful report on Energy Efficiency, in which housing features prominently. We also have the Victorian review of housing. On the other hand we see a plethora of regulatory measures being introduced or proposed covering energy, the disabled, zoning, environmental matters and so on.

The open nature of the Australian housing market and its network of extensive sub-contractors has served the consumer well over the years and clearly contributed to low prices, especially compared with the heavily unionised commercial building sector.

In simple terms the pure house price has moved in line with the Consumer Price Index. The basic house itself has increased in size and in its features. Material input prices have fallen slightly but it is the labour arrangements within the industry that have kept down costs and prices.

Not that we can just sit back and continue to enjoy the cost competitiveness that is such a feature of house building. The industry's low costs are vulnerable from two directions. The first is the union movement, increasingly desperate to arrest its slow decline (only 18 per cent of private sector workers are now members of unions and far more than that -- 28 per cent are self employed). Because of unions' close ties to the Labor Party, we can expect continued assaults on the non-unionised nature of the housing industry, assaults which if they were to prevail would markedly raise costs.

Secondly unions are now vulnerable to the roaming industrial safety officers like union bosses Bill Shorten and Martin Kingham, ever willing to bring on a dispute as the means of justifying their union fees. These men, master wreckers of workplace efficiency, have done a four day course that under Victoria's Occupational Health and Safety Act entitles them to invade any workplace and investigate safety concerns. The job started by the Hawke Government in curbing such practices by setting up a Royal Commission was only half done and construction costs in Australia remain twice those of the world's best practices found in southern USA and Singapore.

By contrast, the housebuilding sector is a haven of industrial tranquility. There are however disturbing increases in regulation and evidence of regulatory barriers being erected to new competition.

In New South Wales, builders are now required to ensure that all power tools used on a building site are checked for safety by a qualified electrician every three months. It is hardly necessary to have expensive checks on 50 or more tools, some of which are used only once a year. It is even more doubtful that "tools" like portable radios and the kettle for morning tea should be as regularly and rigorously tested as heavy equipment. The home buyer pays for this nonsense.

Builders are supposed to meet every visiting contractor on site and discuss their work practices with them, no matter how experienced the tradesperson or how simple the job to be done. Builders and site managers are even expected to be responsible for ensuring their workers protect themselves against the sun.

Other measures have been taken that will adversely impact on house prices. In the main these have been the result of regulatory "capture" and a symbiosis between regulators and the occupations they control.

In the past, the house builder was normally a tradesman who gained sufficiently wide experience to take on a management role in the project. The system of sub-contracting greatly facilitated this.

More recently there has been a rise in credentialism. Unlike in the past, builders now have to take written tests and demonstrate to the authorities a knowledge of the system that has not proved to be necessary in the past. One outcome has been an increase in people purporting to be "owner-builders" to escape the regulatory restraint.

This in turn has led to a vast expansion in the so-called owner builder applications which accounted for 37 per cent of building permit applications in Victoria last year. One facet of this has been the considerable limitations on the ability of an owner-builder to construct new houses and major extensions. As a result, provisions have been introduced in Queensland, NSW and recently in Victoria that are targeted against the owner-builder. In some cases they require the would-be owner-builder to attend a completely useless building course to force up the regulatory costs of opting for this method of building. These provisions have no effect in terms of the safety or functionality of the work (mandatory insurance is necessary in any case and there is no evidence that owner builder work is any less satisfactory than that built by registered builders). In fact, owner-builders are based on the same sub-contracting principles that prevail throughout the industry -- nobody actually lays the bricks or installs the roof trusses.

Governments have introduced increased cost impositions on new houses. NSW has an array of measures that must be incorporated into new houses and which involve the unfortunate new home buyer with unwanted costs. In Victoria, similar measures were introduced with the Plumbing (Water and Energy Savings) Regulations 2004. Under these regulations, people buying new houses must install low pressure water valves. In addition, they have a choice of installing a 2000 litre rainwater tank or a solar heating system.

COST IMPOSITIONS ON HOME OWNERS

That new set of regulations was introduced after a Regulation Impact Statement (RIS) had been prepared, an RIS that was woefully inadequate. This cited but failed to quantify savings from reduced greenhouse gas emissions. It made no attempt to quantify the reductions in consumer satisfaction that the RIS admits will result from the implementation of the proposals, or to acknowledge them via a sophisticated integration of quantitative and qualitative elements. In addition it relied on Keynesian multiplier effects (e.g. increases in employment, gross state product etc) to reach its conclusions, when these "benefits" are not accepted as a legitimate element of economic and/or cost/benefit analysis by a great many experts. The increased activity from regulatory forces was considered as a benefit, whereas in fact such measures merely involve a transfer of expenditure into areas that would not be preferred absent the regulatory coercion.

The net benefit for the water to the individual household storage alternative is based on cost savings estimated at $11 per annum. These savings offset capital costs of $1895 added to which would be costs of loss of useable space and maintenance costs that will be incurred. Even without these other costs, it is doubtful that the effect of these outcomes on individual households could be positive at any feasible discount rate. This reinforces the case for ensuring that the government quantify the social and environmental benefits that are expected.

The new home buyers' alternative regulatory choice, solar heating, involves an up-front outlay of $2000. This is for an unreliable energy supply that costs three times as much as conventionally generated electricity.

THE FUTURE OF PLANNING LAWS

The Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission is conducting an inquiry into building rules and hopefully this will be the prelude to a much needed bonfire of these regulatory measures, and will flow on to other states.

The restraints on supply together with the imposts placed on developers have clearly been the major, if not the only, factors in pushing up the prices of housing.

It is odd that there is not a massive protest about this on the part of the perpetually indignant. After all, we are talking about speculators, local government corruption and extortionate rental profits being amassed by the "passive" landowner. These forces are aided and abetted by very prosperous individuals living in areas that are relatively close to major urban areas but have features of remoteness and exclusivity that would be disturbed by influxes of riff-raff.

All this is at the expense of the weakest and poorest members of society -- the mainly young first home buyer.

Gradual relaxation of restraints, restricting area restraints only to areas of great natural beauty such as national parks and so on. Considerably restraining requirements on builders to set aside land for public use. Developer-builders are in an intensely competitive system and they need no prodding by socially active regulators to press them in directions that their customers want.

The housebuilding industry and its construction counterpart are chalk and cheese.

But a deep shadow has been cast across the industry. State governments seem intent on throttling the industry and on smothering the attempts of first home buyers to get a foot on the property ladder. The most visible aspect of this is the escalating stamp duties especially in NSW and Victoria. However this is only the tip of the impositions the industry and its would-be customers must carry. Housing is vulnerable to do-gooder regulators, social engineering planners and corrupt political entrepreneurs. This has meant regulatory cost impositions piled one on the other.

The clearest area of this is in access to land. Government zoning laws magnify the spectrum of land costs so that land worth a few hundred dollars in undevelopable rural areas increases to a value of $100,000 plus for newly rezoned sites. Constrained land zoning, lengthening approval processes, increased requirements on developers for "sustainable and sensitive" land utilisation, the need to employ well connected consultants to shepherd proposals through the planning process all take their toll.

The Productivity Commission shows that while the building costs of houses increased by 100 per cent over the past 20 years (partly because house size has increased) land blocks over the same period increased by 250 per cent -- in spite of blocks sizes being reduced. The upshot is that typical housing costs on the periphery of Sydney account for only 37 per cent of the house/land package; in Melbourne the share is 47 per cent.

The unwitting new home buyer pays all for all of these extra costs.

In addition the plethora of agencies to "advise" on issues ranging from good design, noise insulation greenhouse mitigation, improving housing accessibility, and so on is creating an avalanche of additional costs. This is most significant in NSW. Not only is NSW the state where ALP social engineers and fix-it men have become most rusted onto the business of government, but the Carr nanny has now lost the restrainer of Treasurer Egan and replaced him with a socialist who will fan the flames of regulation rather than curb the Ministry's regulatory zeal with a damp cloth.

In May, compared with an increase in new dwellings of 13 per cent in the rest of Australia, NSW saw a 22 per cent decrease. This is party because of the constraints of development land around Sydney and the cost loadings on that land that the government has imposed. But, added to these are the increased costs of regulations on energy use and water targets for all new homes built in NSW. The State's Building Sustainability Index (BASIX) requires costly energy and water saving measures.

Victoria is not far behind. An inquiry into housing by the Victorian regulator has already missed its June 30th deadline for the publication of its draft report. One deadline that was not missed was the introduction of State's new 5 star housing regulations. Jubilantly announced on the 30th of June by Ministers Hulls and Thwaites, these foist onto the hapless new home buyer unwanted and costly energy saving requirements, water tanks, additional water piping better glazing and, wait for it, "clever" internal design.

Victorian developers and home buyers got in quick and registered record approval rates in the month before the latest regulatory slug came into effect. But the new costs will work their way through the system. Their effects will please middle aged armchair environmentalists secure that their own real estate values are immune from such charges. But their acts of supposed public service are at the expense of young, less well off aspiring home owners. The new building charges are yet another cruel blow from the Baby Boomers on their children's generation.