''Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,'' wrote William Wordsworth of the fall of the Bastille, ''But to be young was very heaven!''

For many Egyptians today, the street protests in Cairo and elsewhere perhaps hold a similar romance. But just as the French Revolution turned into the Jacobin Terror, so might the widespread unrest on the Arab Street lead to instability and bloodshed in Egypt and the broader Middle East.

Several observers -- from liberal idealists on the Left to neo-conservatives on the Right -- suggest it wrong and churlish to dismiss the wider significance of the week-long uprising to end Hosni Mubarak's 30-year rule.

Writing in The Washington Post, former Bush administration official Elliot Abrams argues: ''The massive and violent demonstrations underway in Egypt, the smaller ones in Jordan and Yemen, and the recent revolt in Tunisia that inspired those events'' suggest that ''Arab nations, too, yearn to throw off the secret police, to read a newspaper that the Ministry of Information has not censored and to vote in free elections''. Bush's ''freedom agenda'', he argues, has been vindicated.

But these are early days and there is still treacherous ground to cover. There are serious reasons to be tentative in one's judgment of the changes taking place not only in the largest Arab state but in the broader Middle East today. Simply put, democrats the world over should be careful what they wish for.

For years, commentators from the Left -- Robert Fisk, John Pilger, Noam Chomsky -- to neo-conservatives on the Right -- Mark Steyn, Fouad Ajami and Abrams himself -- have cynically scolded successive administrations for propping up Mubarak who has denied democracy to the Egyptian people.

For the Left, Uncle Sam kept in power a corrupt and repressive regime for pragmatic reasons of self interest: Israel-Palestine, Hamas and Gaza, security for Gulf oil supplies.

For the Right, the US policy to support Cairo on the grounds that it prevented the turmoil of something worse helped give birth to 9/11-style terrorism. In neo-con-speak, at last we can ''drain the terror swamp'' at its Mideast source, topple a dictator whose illusion of stability gave comfort to Al Qaeda, and make the US and the region safer in the long run.

But many seasoned hands predict a very different scenario: that if democratic elections were held, they would more than likely represent a landslide for the Muslim Brotherhood. In other words, far from ushering in a new era of democratic prosperity and a stable peace, an Egyptian revolution could lead to a period of virulent anti-Americanism and Islamic extremism.

That does not mean the US should continue to give unqualified and unconditional support to Mubarak. It's just that elections are no panacea in a nation or region with little liberal democratic traditions; that president Obama's cautious wait-and-see approach is more than justified; and that, if anything, Washington should foster a Mubarak-led transfer of power rather than one led by the street protesters.

As the Iraq experience has shown over the past eight years, removing a dictator is the easy bit; ensuring people power leads to peace and freedom is far more complicated and fraught with danger.

To work, democracy requires, among other things, a degree of prosperity and order. And it requires that the losers respect the rights of the winners to rule and the electoral majority respect the rights of the minority to the untrammelled benefits of civil society -- including freedom of speech, organisation, religion, and an impartial judiciary. That is, a democracy has to embrace the idea of a loyal opposition.

Look at Egypt and it appears that none of these conditions can easily be met anytime soon. The protestors might be young, but they are not wholly secular and many are unemployed. Mohammed ElBaradei is touted as an alternative leader, but serious doubts dog his ability to represent any constituency inside Egypt. The Muslim Brotherhood is the only organised political group, but it is also an extremist outfit that supports Hamas and Tehran, opposes Israel, the US and the 1979 Camp David peace accords, and threatens regional and global counter-terrorism efforts.

Attacks are mounting against president Obama for failing to offer sufficient support to the protestors, with claims that Washington is siding with the 82-year-old dictator against the Egyptian people. Obama's approach to the crisis, taken together with the annual US financial support to Cairo worth about $US2 billion, is derided as ''realist'' -- typically with quotation marks -- as well as uncaring and even amoral.

These critics on both Left and Right clearly fail to grasp the very real limits imposed on America's power to implement changes in Egypt and anywhere else in the region, for that matter. As veteran State Department adviser Aaron David Miller points out in The Much Too Promised Land: America's Elusive Search for Arab-Israeli Peace (2008), the US finds itself ''trapped in a region which it cannot fix and it cannot abandon,'' a region where Washington is ''not liked, not feared and not respected.''

In these circumstances, it's surely simplistic to denounce Cairo for denying democracy to the Egyptian people. What if elections brought to power jihadists and terrorist supporters such as the Muslim Brotherhood? What if voters in Saudi Arabia prefer an Islamist zealot in the mould of Osama bin Laden to a moderate reformer such as Crown Prince Abdullah? What if electors in Yemen replaced Ali Abdullah Saleh, in power for nearly 25 years, with Islamist hardliners and terrorist supporters?

In his book The Arabs: A History, Eugene Rogan says that in ''any free and fair election in the Arab world today, I believe, the Islamists would win hands down.'' He goes onto say that ''the inconvenient truth about the Arab world today is that, in any free election, those parties most hostile to the United States are likely to win.''

The point here is not to denigrate the US. It is that because nations such as Egypt are still modernising, they are open to all the disturbing and dislocating ideological forces that this process will unleash. That is why democracy could degenerate into plebiscites that, far from leading to moderate and sensible governments, would add legitimacy to authoritarianism and extremism.

As it happens, Islamists have a lot of things in their favour to exploit any political chaos: the talent to develop a compelling ideology, the enthusiasm to create parties and appeal to supporters, the money to spend on election campaigns and the will to intimidate rivals.

History, moreover, shows how the most unsavoury groups can use elections to win power. Remember a democratic process produced Chancellor Hitler in 1933. Two decades ago, Muslim fundamentalists had more or less won free and fair elections in Algeria before the French convinced the government to stop the democratic process. On the eve of Saddam Hussein's toppling in 2003, elections in Turkey brought to power Islamists who denied the US access to its territory for the liberation of Iraq.

To reiterate: none of this means that Washington should blindly support the Mubarak regime. But strongly backing the protesters is also risky. Instead, the Obama administration should proceed cautiously and prudently and without illusion towards its most important Arab ally. Call on the government and protestors to restrain from using force. Keep quiet publicly and work behind the scenes to encourage Mubarak to transfer power in a peaceful manner and on terms that save him face. And don't agitate for radical change which would merely lead to unintended consequences.

Which brings us back to Wordsworth's ironic poem about 1789. He recognised that the toppling of an authoritarian monarchy had led to more harm than good, that if the fall of the Ancien Régime represented the birth of the Rights of Man, it also marked the beginning of a tyrannical state and a new age of terror.

Today the spectre of Wordsworth haunts Egypt. For there is a real possibility that the more democratic and revolutionary Cairo and the Middle East become, the more Islamist, authoritarian and anti-American the region will be. That's in neither the US nor the Arab world's interest.

John Winston Howard is Australia's second longest serving Prime Minister and the twelfth longest serving member of the House of Representatives.

John Winston Howard is Australia's second longest serving Prime Minister and the twelfth longest serving member of the House of Representatives. It is a bold decision to name your book from one of the most influential books in liberal thinking. But Daniel Hannan's The New Road to Serfdom is not some second-rate spinoff of Friedrich Hayek's classic. Instead, it applies the messages and the warnings of The Road to Serfdom to the United States of today. Of all people, Hannan has real-world experience with the growth of a powerful ''super-state'', having been a Member of the European Parliament since 1999. This period has been a time of intense centralisation, in both political and regulatory terms.

It is a bold decision to name your book from one of the most influential books in liberal thinking. But Daniel Hannan's The New Road to Serfdom is not some second-rate spinoff of Friedrich Hayek's classic. Instead, it applies the messages and the warnings of The Road to Serfdom to the United States of today. Of all people, Hannan has real-world experience with the growth of a powerful ''super-state'', having been a Member of the European Parliament since 1999. This period has been a time of intense centralisation, in both political and regulatory terms. Back around the turn of the century, social capital was the hottest idea in the social sciences. Popularised by Professor Robert Putnam of Harvard University in his book Bowling Alone, politicians, academics and commentators were entranced with the idea of a link between economic prosperity and how connected a community is socially.

Back around the turn of the century, social capital was the hottest idea in the social sciences. Popularised by Professor Robert Putnam of Harvard University in his book Bowling Alone, politicians, academics and commentators were entranced with the idea of a link between economic prosperity and how connected a community is socially. Keith Hancock's stature as an historian is emphasised by a quote from Stuart Macintyre, prominently cited on the dust jacket of this new biography, that ''if there were a Nobel Prize for History, Hancock surely would have won it.''

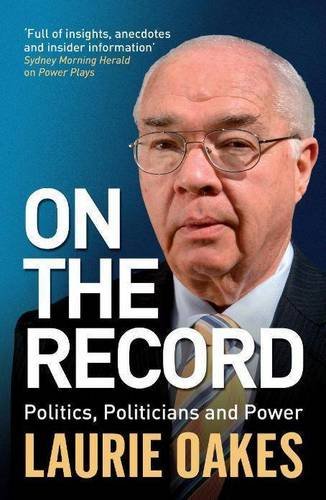

Keith Hancock's stature as an historian is emphasised by a quote from Stuart Macintyre, prominently cited on the dust jacket of this new biography, that ''if there were a Nobel Prize for History, Hancock surely would have won it.'' The Canberra press gallery has over 150 journalists. All of them are very competitive, seeking to break that story that will propel them to national fame, or add the suffix ''-gate'' to some scandal they have uncovered. Australians would struggle to name a handful of these journalists, just as they would probably struggle to name more than a handful of politicians.

The Canberra press gallery has over 150 journalists. All of them are very competitive, seeking to break that story that will propel them to national fame, or add the suffix ''-gate'' to some scandal they have uncovered. Australians would struggle to name a handful of these journalists, just as they would probably struggle to name more than a handful of politicians.