Hal Clough Lecture 2005,

Perth, 25 October 2005

The Australian federal system is at a crossroads.

It needs to be reinvigorated or it will become a costly vestige of a noble but failed experiment.

There is no possibility of the states disappearing altogether. Australians are far too constitutionally conservative to allow this to happen. The states are however on a path to become little more than administrative units of the Commonwealth -- and costly ones at that.

While theoretically a federal system remains the optimal system of government for a large, economically diverse country in a rapidly globalising world, it depends on how the system is structured and how well it works. Federal systems can and do fail. They can increase the size of government rather than limit it. They can enhance the power of vested interests over the general interest.

Federalism is inherently messy. By design it disperses power vertically and horizontally across jurisdictions, resulting in a multiplicity of programmes, policies, taxes, regulations, bureaucracies, legislatures and lobbyists. In the absence of countervailing benefits, federalism will result in excessive government.

This point has not been reached in Australia, but it is fast approaching. The task of renewing the federal compact will be difficult, as it will go against the flow of over a century of steady centralisation. But it is worth the effort.

The task is to rediscover the virtues of federalism and then to start rebuilding the institutions which support it.

THE BENEFITS OF FEDERALISM

TAMING THE LEVIATHAN (1)

Good government is an enormously valuable asset -- not only in terms of assisting economic growth but in protecting human rights. On the other hand, bad government has the capacity to hold people in abject misery and be captured by those who control its levers.

As James Buchanan said, "Government is indeed Leviathan, a giant that can help us or crush us". (2)

In 1995 I stated, "The critical and never ending task with which society has to struggle, therefore is to create devices that constrain the politicians and the bureaucrats so that they act in the interest of the citizen [which is] the real principle of governance". (3)

Over the centuries, societies have built many mechanisms to control the Leviathan. The most successful has been the Western liberal democratic tradition of government. The elements of this tradition are well known: representative democracy, sovereignty resting with the people, the rule of law, equality before the law, the right to own and trade property, and the recognition of -- and the respect for -- basic rights and freedoms.

The American Revolution added one more layer to that tradition -- what we in Australia understand as "checks and balances". To foster these, American founders enumerated and divided power between different levels of government. The aim was to disperse power so as to limit its accumulations and abuse. Dispersed power is limited power.

Federalism offers the possibility of refuge from exploitation. This is a valid concern in modern Australia. One need only cast their memory back fifteen years to Joan Kirner's Victoria when her big government policies were undermining the Victorian economy and allowing political activists to gain undue control over the instruments of state.

Our federal system came to their rescue. Other states, particularly Queensland, pursued markedly different policies, and provided a refuge for many hundreds of thousand Victorians.

Or think back closer to home in Western Australia just four years ago, when the Gallop Government effectively removed the basic right of people and businesses to freely enter into individual labour contracts.

The individual contracts were, after decades of prohibition, introduced by the Court Government in the mid 1990s. They were widely adopted, particularly in the State's mining sector, and contributed greatly to industrial harmony and improved competitiveness. Their removal in 2001 could not have come at a worse time. Individual contracts were a crucial plank in the mining sector's restructuring and expansion aimed at reaping the benefits of rising China.

The federal system came to the rescue. The Howard Government's 1996 industrial relations laws also allowed individual contracts, and most of the mining sector was able -- albeit at substantial cost -- to shift over to the Commonwealth system. This enabled the sector to retain its competitive arrangements, make necessary investments and to tap into Chinese markets. The lifeline provided by the Commonwealth's legislation has had profound and positive benefits for Western Australians.

States are not always the white knights of federalism. They can be as abusive to their own citizens as can the Commonwealth. Moreover, the benefits of federalism arise from the contestability amongst government vertically as well as horizontally.

The most important benefit of federalism in Australia is its ability to inject competition into the processes of government. It gives people choice as to how they will be governed.

Seen in this light, federalism is a kind of competition policy for government.

By its very nature, government displays all the characteristics of monopoly, with the added twists that it is sanctioned and enforced by law. But once mobility and choice of jurisdiction is introduced, the potential for competition follows.

Given that the big picture reforms of the future lie in injecting competition into the government services of health, education, welfare and environmental protection, federalism has the potential to play a key role.

Examples of the benefits of constructive federal competition abound.

Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen in Queensland pursued a markedly different set of economic policies to the other states. He ran the State's finances as he ran his farm. He hired a good, conservative accountant as Treasurer, who balanced the books, built-up cash balances in case of drought, kept taxes low, ensured that government businesses were efficient and self sufficient and set aside funds for future liabilities such as public service superannuation. But Sir Joh was not too keen on fiscal transparency. Indeed, he went to great length to hide the surpluses.

Derided as simple and undemocratic -- which, in part, they were -- most of Sir Joh's policies contributed to the sweeping improvements in state finances over the last fifteen years. Sir Joh's fiscal approach -- with exception of his poor standards of transparency -- has become the norm at least until recently.

Sir Joh did not achieve this feat of conversion through the power of his intellect or eloquence of oration. Rather he did it through the force of competition transmitted through the federal system.

The other states watched as people, businesses and jobs migrated north to Queensland in response to the sunshine state's more attractive economic environment and quality of life. Other states also finally caught on to the inherent failure of Keynesian policies at a state level.

Clearly not too many people are going to pull-up stakes and move to Queensland to avoid land tax or other state policies. But some will -- and it is movement of people at the margin that counts. Moreover, while people may be reluctant to move, businesses activity and capital are much more mobile. And this is where the real competitive pressures come.

It isn't necessarily movement of economic activity per se that drives competition, but rather the threat of it. (4) The threat comes from evidence and knowledge that there are significant differences between states and that the home state is unwilling or unable to match the performance of others -- a key motivating force of competitive federalism.

Federalism offers other powerful benefits.

It has the potential if properly structured to limit free-riders. One of the key distortions of government is it tends to offer the lure of a free lunch. It provides valuable services paid-for by others. This induces a positive response and excessive demand for these goods. It also gives rise to people depending on others rather than themselves for funding of services. Since most spillover benefits of government actions are limited geographically, splitting a nation into sub-national jurisdictions makes it easier to align the payment for and benefit from government services.

Federalism also supports the application of the related principle of subsidiarity. The subsidiarity principle is that decision making power should be exercised at the lowest collective unit that produces efficient results. The argument is that the smaller the collective unit the better or more democratic the decision. That is, the closer the decision point is to those who are effected by it, the better. Indeed this was an underlying principle of the Australia's Founder in allocating responsibilities between the state and Commonwealth.

Federal systems are particularly suitable in the modern, rapidly globalising, world.

It is true that the globalisation of markets, communities and ideas are pulling the loci of some decisions and law-making away from local to the national and international sphere. These include laws governing trade, accounting and operating standards for business, some environmental issues such as global warming and even policing in the age of international terrorism.

But at the same time, "place" matters more in a globalising world. As the geographic reach of markets expands from local to global, regional economies tend to specialise and differentiate themselves more and more. As their links with global and national markets increase, they become more different from one another.

Industries cluster in regions most suitable for their productions, which results in even further specialisations.

Accordingly there needs to be often subtle, but significant, differences in policy across regions.

Take Western Australia and New South Wales. Sydney is steadily becoming the business services and financial center of the Australia-Pacific region. Western Australia has in recent decades become a regional centre for the various industries focused on finding, developing and exporting minerals on a huge scale and as a home base for the many skilled professionals working in the region in these activities.

As such the economies of Sydney and Perth have diverged. While their development paths are logical and successful, they require a different mix of policies. Their differences foster divergent values. For example in Sydney the provisioning of extensive national parks, as well as the imposition of environmental restrictions on mining and agricultural development help attract and retain the wealthy financial services workforce. Sydney can also afford to heavily tax housing and promote concentrated high-rise urban living, as the location with which it competes are the high priced financial clusters of Hong Kong, Singapore, London and San Francisco.

In contrast, Western Australia's specialisation is rooted in gaining access to new ore bodies and the development of a large resource base. As a regional home base, the Perth economy is very sensitive to housing prices and needs to place a premium on maintaining the traditional suburban living environment.

Centralised government, with its tendency to promote one-approach fits all policies, will fail to understand, let alone foster, these regional differences. And being controlled by a largely majoritarian political system, they will always tend to see the world through the prism of the larger centres.

But does the Australian federal system work?

So much for theory, the real question is: does the Australian Federal system perform to its potential and, if not, why not?

It does not, because it is not allowed to.

The problem started from the beginning, with the Australian Constitution.

While the Australian founders were well acquainted with the workings of the federal systems in the United States, Canada, and Switzerland, they chose a weaker form of federalism. Although they were aware of the dangers of the Commonwealth Government acquiring excessive taxing powers, they put in place inadequate safeguards against such an eventuality.

They chose a less than complete separation of powers between the executive and legislature. They specified the powers of the Commonwealth and not those of the States, and shared many powers between the two jurisdictions. They specified that, in a conflict of laws, the Federal law would prevail. They allocated considerable taxing power to the Commonwealth.

These decisions provided the capacity and motivation for the Commonwealth to steadily takeover the State powers -- undermining the functioning of the federal system.

The Constitution's greatest weakness is its failure to reconcile the conflicting Washingtonian and Westminster traditions. The primary concern in the Washingtonian tradition is to limit government by dispersing powers across levels and sections of government and embedding then these in a constitution. The Westminster tradition is based on the idea of responsible government where the focus is on the need to empower a single national parliament, unencumbered by a written constitution.

The Australia Founders combined the two traditions into what has been labeled the Washminister Model. Predictably, at least in hindsight, the Australian politicians, Federal and State, have preferred the less restrictive and more positive Westminster perspective

Federalism is not a system of choice for people who believe in the inherent benevolence of government. Nor is it a system that pleases politicians. Politicians do not take kindly to competitive pressures over their powers. Perhaps understandably they try to respond to the every demand of their constituency, even if it concerns issues outside of their constitutional responsibility.

The dominance of the responsible government ideal, in combination with the relatively weak limits placed on the Commonwealth, has allowed the steady accretion of power in Canberra.

This has been assisted by the failure of the institutions established to buttress the federal system -- the Senate, the High Court, and the Interstate Commission.

TAX AND FEDERALISM

The dominant factor behind the failure of federalism has been the steady accumulation of taxing powers by the Commonwealth.

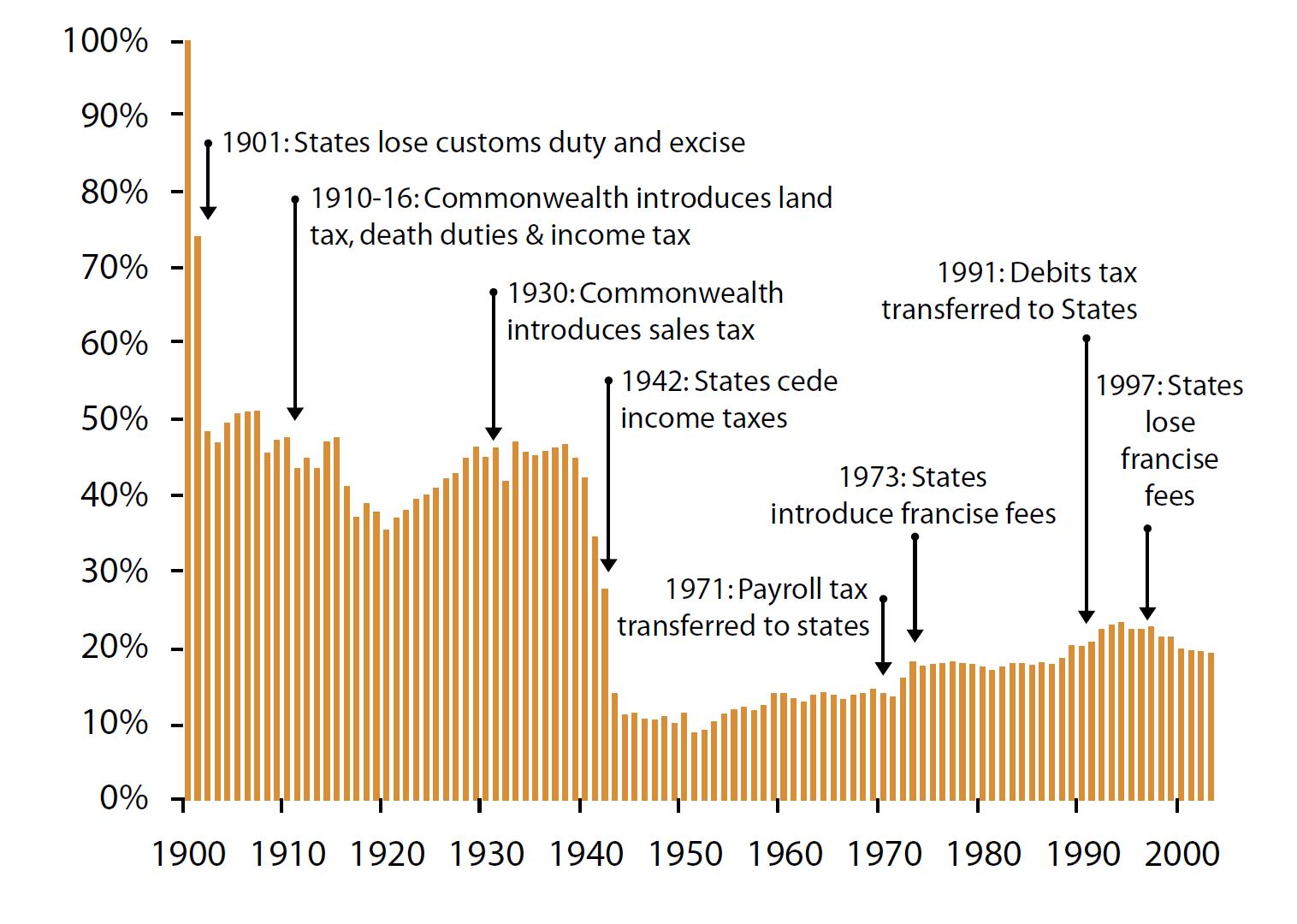

The states' share of total government tax revenue has declined from 75 per cent at the time of federation to less than 20 per cent today. (Figure 1)

Figure 1: State Own Source Revenues, % Commonwealth and State Revenues

Between 1910 and 1942 the states share declined largely as a result of the expansion of the Commonwealths tax base. In 1942, the states' share decline sharply as a result of the Commonwealth taking over income taxing powers from the states. This was initially put forward as a temporary war measure, but remained.

The states were "given" a series of new taxes over the succeeding 50 years; including payroll, franchise fee, debit tax, and more recently the GST (though neither the Commonwealth or the States claim this tax for themselves). These new taxes did allow their share of the tax base to increase from its low of 8 per cent in 1952. Nonetheless, the states' share of tax revenue remains much lower than that envisaged by the Founders and is once again declining.

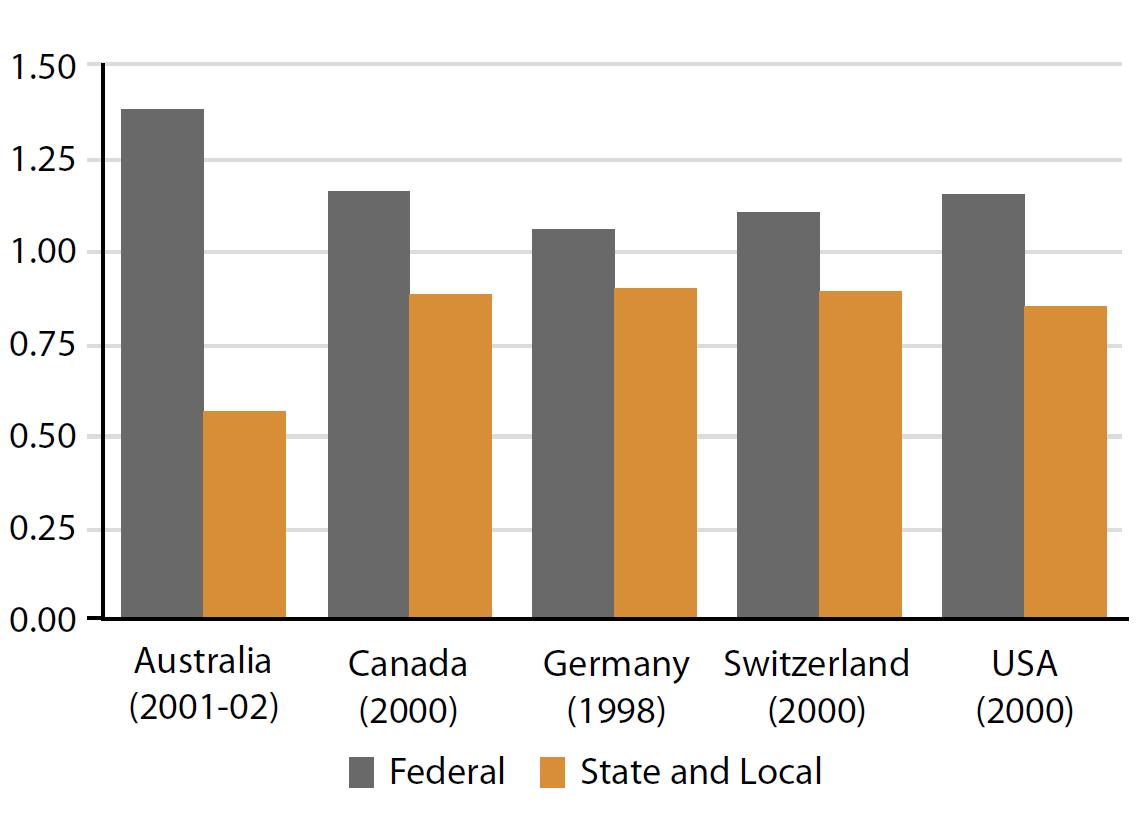

The so-called vertical fiscal imbalance -- the difference between spending and revenue raising at Commonwealth and State levels -- is large. It is much larger than in comparable federal nations. (Figure 2)

Figure 2: Vertical Fiscal Imbalance, Ratios. Own Source to Own Purpose Outlays

The critical assumption that underlies the benefits of a federal system is that each level of government is responsible for raising its own funds. In order for competitive federalism to work the states must have the powers to vary their taxing and spending policies to compete for economic activity. If the Commonwealth raises the bulk of tax revenue in a nationally uniform manner, then the potential for this competition is muted. If central government collects money from all to provide service to a limit number then free riding is encouraged.

The potential for a federal system to act as protection against the accretion of power is dependent upon revenue raising being shared across the jurisdictions according to their responsibilities. If the central government retains spending power far in excess of it own spending requirements, as is the case in Australia, its powers are not limited but augmented.

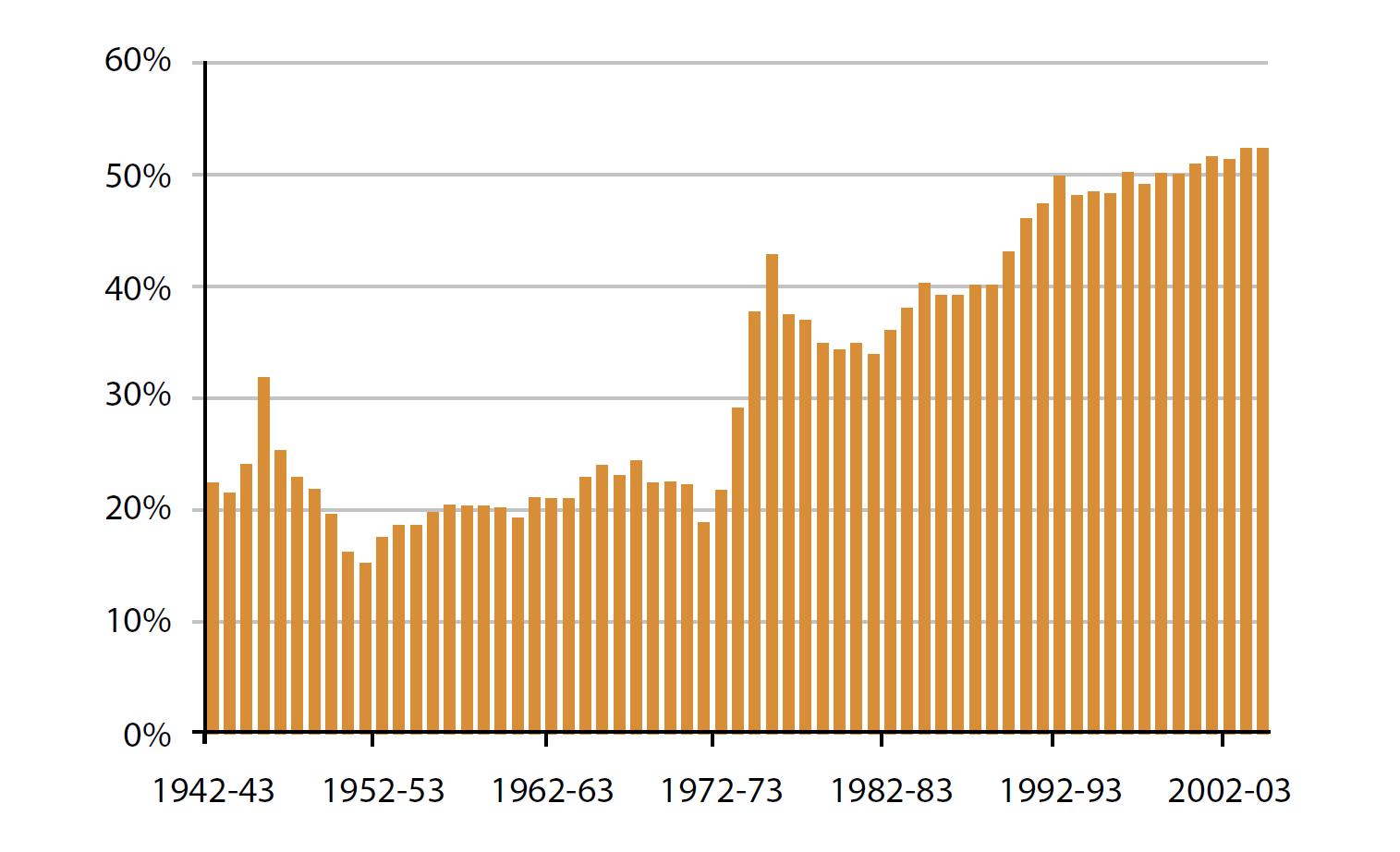

Importantly the GST has significantly increased the dependence of the states upon the Commonwealth. (Figure 3)

Figure 3: Revenue Sources, All States, 1999-2000 and 2005-06

The Commonwealth has used this control over the taxing power to become involved in spending activities of the states. The share of Commonwealth Grants with strings attached has grown dramatically.

It has increasingly used its control over the public purse and its constitutional powers -- particularly its external affairs and corporation powers -- to directly takeover state powers.

As a result, the Commonwealth and the states share responsibility for over half of the functions provided by the public sector. This has not only blurred the lines of responsibility but has resulted in most areas being run by large bureaucracies. It has also led to wasteful levels of overlap and duplications.

The best, and really the only, detailed research on the extent of overlap and duplication in the public sector was undertaken by us ten years ago. (5) It found that in 1995-96 there were 466 separate inter-government sub-committees involved in managing Commonwealth tied grants to the States, each with different and often complex rules. The study also found that parliaments, particularly state parliaments, played a minor role in authorising administrative arrangements, setting objectives and assessing the performance of the grants. Instead of being responsible to democratic bodies, programmes were in the main initiated and managed by the bureaucracy.

In a separate study, the National Audit Office concluded that "for many programmes [tied grants] accountability to the Commonwealth is poor". (6) State programmes are far worse. The study also found that few tied grants had clear performance objectives and that their matching requirements bore no relationship to the spillover effects that they were supposedly meant to address.

To add to this is the allocation of general purpose grants administered by the Commonwealth Grants Commission (CGC). The CGC methodology aims to provide each state and territory the financial capacity to provide a uniform set and level of services irrespective of differences in cost and revenue raising ability. This set of services is very comprehensive, including debt levels and superannuation liabilities. The benchmarks used in the assessment are based on current policies and cost structures. The benchmarks do not consider best practice, efficiency or effectiveness.

The methodology is designed to be policy neutral. But of course it isn't. Instead, it provides an incentive for uniformity, it compensates for inefficiency, it dulls the incentive for reform and experimentation, and it facilitates expansion in the size and function of government.

More money is now being poured through the system than is needed. Even if one accepts the need for equalisation through the CGC, the $37 billion in GST revenue now being allocated is far in excess of what is needed to achieve an equalisation of capacity. The over-funding further distorts the incentives to State governments.

It is wrong to assume that the erosion of fiscal independence of the states has been totally foisted on the states by the Commonwealth. While the states have -- at times -- resisted the process, they have more likely to either quietly accept it or actively promote it.

Sir Joh's famous statement "the only good tax, is a Commonwealth tax" was not made as comment on optimal tax policy, but rather his desire for the Commonwealth to "pluck the goose" for him. This view has been widely held by Premiers through history.

The CGC process is of the states' making. And as the Howard Government has made clear, it is in the states' collective power to reform it.

It is also wrong to see all the efforts of co-operation amongst government as wrong. Over the last 100 years some powers have naturally and appropriately migrated to the Commonwealth.

Some degree of co-operation is necessary between government -- for instance agreement as to the rules under which states compete. A good example of this has been the National Competition Policy process.

Nonetheless, the centralisation of taxing and spending powers and the intermingling of responsibilities have grown far beyond the requires of an effective federal system.

Figure 4: Special Purpose Payments, % Total Payments to the States

SUMMARY

While federalism has the potential to be the optimal system of government for a modern Australia, the current system falls far short of that optimum.

In order for competitive federalism to work, states must be responsible for raising their own revenue and controlling their spending. Under the Australian system they do not.

The signs of a failing federal system abound. Innovation in the provision of state services has ground to a halt. The focus of all states, now that the GST has delivered the growth tax wanted, is on spending.

States are receiving near record revenue growth -- an average of 8.5 per cent per year over the last few years. This has been generated by a booming economy, the GST, and high rates of state taxes.

Despite their overflowing wealth, the States have shown an intense unwillingness to reduce taxes, even those that are small, destructive relics of the pre-GST era.

Instead, the States are spending money on virtually everything. State spending over the last two years has been growing at 8.6 per cent per annum. Public servant salaries have been growing at between 5 and 7 per cent per year and in some states the salaries bill is growing at a rate of in excess of 10 per cent per year.

Innovation in the state sector has ground to a virtual halt.

Most of the reform that is coming through is being forced on the states through the lure of National Competition Policy (NCP) money.

Moreover, there is growing trend amongst state governments to seek national agreements which limit the scope for policy variation. In short, they are colluding to limit competition.

Of course, the good economic times have lured the states into complacency -- the money is easy, so they take it easy. But there is little doubt that the perverse incentives of our crippled federal system is encouraging them down this route.

WHAT TO DO

Supporters of a functioning federal system must seek to go back to something close to the original constitutional settlement, where the states were responsible for the majority of government powers -- and were required to raise their own funding.

Such a reconstituted settlement would mean:

- states regaining access to a share of income taxing powers

- far fewer funds distributed through the Grants Commission's process

- special purpose grants and inter-government committees reduced in number and made more outcome focused and transparent.

This should be the agenda. The redesign of the federal system will require a concerted effort as well as leadership and institutional support. Australians are a pragmatic lot -- change for its own sake is not in the Australian nature. While many recognise in a general way the failings of the federal system and the need for its reform, they need to be convinced of a workable alternative.

Moreover, given the current tax and spending policies of the states, I doubt that many people would want to hand the states even partial control over income tax.

The initial leadership for reform of the federal system must come from voters and specifically from policy-makers -- the individuals and organisations which develop debate and market ideas.

During the 1980s and early 1990s reform of the federal system was on the agenda. The rationale and agenda for reform was widely debated and supported, albeit not uniformly. The result was two major attempts at reform of the federal system -- the Hawke New Federalism Initiative of 1990 and the National Competition Policy initiative of 1995.

During the last ten years, federalism has fallen off the agenda. But there is now movement again.

We plan to re-enter in the debate with the re-establishment of the States Policy Unit. The Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Western Australia has also been a long standing participant in the debate on improving the federal system. It plans to soon release a document on the issue. Similarly the Productivity Commission has organised a conference on productive reform in the Federal system later this week.

It is also vital that academia be brought back into the debate. With the demise of the Federalism Centre at the Australian National University, research on federalism at Australian universities has waned.

THERE IS THE NEED FOR GREATER SCRUTINY OF STATE SPENDING AND TAXING POLICIES

As Professor Walsh (former Director of the ANU's Federalism Centre) recently stated,

"... competition must ultimately be explained by citizen-voters using some form of benchmarking of their State government against others, and that this is what effectively make state governments compete with each other". (7)

The benchmarking work undertaken in the past by us, CCIWA and others played a vital role not only driving competition between states but enhancing state accountability.

The states face a veritable army of social advocacy groups whose survival lies in keeping the government funding taps open. These groups not only act as lobbyists for more spending but assist the states as they seek more money from the Commonwealth. At the same time the states -- who employ the majority of the country's public servants -- are under the thumb of public sector unions like never before.

Advocacy groups and public sector unions are very satisfied with the status quo. Money is more easily extracted from unaccountable governments than those that must directly face their taxpayers.

THE STATES WILL AGAIN BE BENCHMARKED

Eventually states and the Commonwealth Government must jointly take on the mantle of leadership. To be successful, leadership must come from both levels of government with support of the major parties.

This will not be easy. The current federal government has many centralist tendencies. The Labor Party -- which is in government in all States and territories -- has been at best agnostic towards federalism.

While all governments recognise that the system is not working well and is holding back essential reform, few have been willing to wear the political cost that comes with change.

The redesign process must include reform to the CGC process, re-alignment of roles and responsibilities, and strengthened competition policy.

The states need to take the lead on reforming the Grants Commission process. This will not be easy, as the smaller states and the territories have become highly dependent on interstate subsidies. But it is clearly necessary, and there are a range of options readily to hand

The process of redesigning the federal system must avoid a narrow "states rights" perspective. States do not have rights, people have rights. States have roles and responsibilities, which change over time. Indeed, they have changed significantly over the last 100 plus years. Thus the process must include a pragmatic review of the role of the states not only of their relationship with the Commonwealth, but also with regard to their own citizens.

As the CCIWA recently pointed out, "the concept of subsidiarity ... has broader implications and applications than managing the boundaries of government jurisdictions. It means that government should not interfere in the activities of individuals, families, businesses and civil society except where these are not capable of effective self-management or where their activities might spill over to affect others". (8)

Governments -- state and federal -- have interfered too much. It is time to begin peeling back the role of government by placing greater reliance on competitive markets, innovation, and individual responsibility.

This process has begun but needs to be expanded and accelerated.

Any reform of the federal system must facilitate this, while at the same time realigning the role and responsibilities between the levels of government.

Two areas stand out for realignment: health and schools.

HEALTH

The Australian health system remains mired in bureaucratic control. It suffers from the undue influence of medical providers, its balkanisation into over 60 different programs, and its funding source -- largely Commonwealth through a mishmash of uncapped budgets and run-away entitlements.

The states' role in health has largely been relegated to owning and managing public hospitals -- which in turn are half funded and indirectly controlled by the Commonwealth.

It is time to move to an unified national health market driven by individual needs and with a diversity of competitive providers. The role of the states would change radically under such a system. They will no longer be required to fund it. They may wish to continue to operate public hospitals but as businesses paid for by user charges. Some states may wish to convert their hospitals to non-profit organisations or to privatise them. They will necessarily retain a role in planning and over sight of the heath market, but broadly speaking, their role in health would greatly be reduced.

EDUCATION

Currently, the Commonwealth's role in primary and secondary education is limited to providing quasi-vouchers for non-government schools, providing some funding for government schools, and trying to ensure that national goals are met.

It is time to simplify these arrangements by shifting responsibility for funding and oversight of government and non-government schools to the states -- subject to meeting and reporting on a few valid national standards and to continue to make payment to non- government schools.

These changes -- the shift of health to the Commonwealth and schools to the states -- would greatly reduce overlap and duplication. It also has the potential to substantially reduce the imbalance in spending and taxing.

In some areas -- where the role of state and federal government are inextricably intertwined and where a reform template is available -- the responsibility for reform should be part of a renewed mandate for the National Competition Policy.

With the funding set to run out soon, the initial NCP agenda is coming to an end. Governments are currently considering what to do next. All agree that the process was successful in inducing the states to put into effect market-based reforms more thoroughly and quickly than would other wise be the case. Federalists might lament the need for a national approach and the need for fiscal inducement, but given the distorted incentives in the federal system it was probably necessary.

The NCP has enhanced the status of the states by buttressing them against the slide into dirigisme.

The NCP's core principals -- transparency, market-based competition and measurement of cost and benefits of regulation -- are simply the underpinnings of good government. These principals can and should be applied to a wide range of government services. A nationally coordinated approach is particularly suitable for those areas where the roles of state and federal governments are inextricable intertwined and where there is a agreed reform agenda.

For instance, suitable candidates of an expanded NCP are vocational education and aged care.

Environmental policy is another area where all levels of government interfere with each other, often resulting in illiberal and duplicative policies. The states are particularly guilty of undermining basic rights, including the protection of private property and due process. The Commonwealth's approach is a little better, but not much. However, rather than trying to improve the approach of the States, the Commonwealth invariably seeks to duplicate and/or override the states to impose uniformity

Here expanding the NCP process of subjecting environment regulation to cost -- benefit analysis and requiring market-based approaches may be helpful.

For environment policy however, the real solution lies with constitutional reform at the state level. While the Australian Constitution places limits on the Commonwealth's ability to take property without compensation, state constitutions do not. This needs to be addressed.

A debate about state constitutions would also facilitate wider public dialogue on the role of the states -- essential to renewing the federal system

In the end, the key reform will be for the states to be able to level an income tax through the Commonwealth system, as in the United States. Only when the states are responsible for raising a greater share of their own revenue can a federal system function properly.

There is work to do, and federalists must get to the task.

REFERENCES

1. The next two sections draw heavily from: Wood, R.J. (1996), Restoring the Balance: Tax Reform for the Australian Federation.

2. Buchanan, J (1975), The Limits of Liberty: Between Anarchy and Leviathon, Chicago: Chicago University Press.

3. Wood, R.J. (1995), Competitive Federalism: Promoting Freedom and Prosperity, Federalism Issues Paper No. 3, January.

4. Walsh, C. (2005) Competitive Federalism: Wasteful or Welfare Enhancing?, Productivity Commission Roundtable: Productivity Reform in a Federal System, October.

5. Wood. R.J. (1996), Roles and Responsibilities in the Australian Federal System.

6. ANAO (1995), Specific Purpose Payments to and through the States and Territories' Report No. 21, 1994-95, Australian National Audit Office, AGPS.

7. Walsh, C. (2005), page 23.

8. CCIWA (2005) Federalism in Australia: A Discussion Paper, Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Western Australia, Draft, September 2005.