Occasional Paper

INTRODUCTION

This report is about improving housing affordability in Melbourne. The report concentrates on home ownership, the most common type of housing tenure in Melbourne. Home ownership retains its position as the key financial aspiration of the vast majority of Melburnians. However, high prices also eventually mean high rents. So while this report concentrates on home ownership, recent and continuing large rent increases demonstrate the flow-on effects to renters of policy settings which inflate housing costs.

In reviewing the costs of new housing in Melbourne the conclusion is that housing is unaffordable for ordinary families who are not already home owners. The cause of this is state government policies, especially restrictions on land release. In total, government policies, taxes and charges add $135,000 to the cost of a new home, or 32 per cent of the cost of a $370,000 house and land package. This means that a family on median income buying a house at the median price would be paying 56.2 per cent of their after tax income on housing.

We have had a long interest in housing affordability. Through numerous publications, including the book The Tragedy of Planning: Losing the Great Australian Dream, we have consistently argued housing in Australian cities is too expensive and this is caused primarily by flawed government policies restricting the growth of new housing developments on the periphery of cities. In the case of Melbourne, planning policies such as Melbourne 2030 involving an urban growth boundary, have added an estimated 15 per cent, or $56,000 to the cost of a new home. Further costs are added through taxation.

Melbourne is doing better than some other Australian cities, notably Sydney and Perth whose planning policies have created even greater shortages of land for housing. However, in a global survey of housing affordability across 159 major housing markets, Melbourne was the 23rd least affordable and was characterised as severely unaffordable. (1) Housing is a fundamental need and the largest asset most Melburnians will purchase. It is vital that policy makers redress this unaffordability, the key losers from which are families on lower incomes and younger people.

If home ownership is not to be restricted to those whose parents can pay for them, governments must actively pursue policies to improve housing affordability.

These considerations are also important in a strategic sense if Melbourne in particular is to enhance is role by attracting and retaining productive people.

Melbourne and other urbanised parts of Victoria largely comprise owner-occupation of detached dwellings. On the latest statistics 71.9 per cent of Melbourne dwellings were separate houses and a further 11.4 per cent are in semi-detached or terraced houses. (2) Over long periods of time, and in differing economic conditions, Melburnians have continued to express a strong preference for their own home, often in a new suburb, on a relatively large block of land. Indeed as Figure 1 shows, the current top ten recipients of the First Home Owner Grant purchase their homes in suburbs on the periphery.

Figure 1: Top ten recipients of First Home Owner Grants, Victoria (July 2006-May 2007)

| Rank | Postcode | Suburbs | Applications |

| 1 | 3030 | Werribee, Werribee South, Derrimut, Point Cook, Cocoroc, Quandong | 830 |

| 2 | 3977 | Cannons Creek, Cranbourne, Cranbourne East, Cranbourne North, Cranbourne South, Cranbourne West, Devon Meadows, Junction Village, Sandhurst, Skye | 793 |

| 3 | 3023 | Burnside, Burnside Heights, Cairnlea, Caroline Springs, Deer Park, Deer Park North, Ravenhall | 683 |

| 4 | 3029 | Hopper’s Crossing, Tarneit, Truganina | 679 |

| 5 | 3064 | Craigieburn, Donnybrook, Kalkallo, Mickleham, Roxburgh Park | 571 |

| 6 | 3805 | Fountain Gate, Narre Warren, Narre Warren South | 450 |

| 7 | 3037 | Delahey, Hillside, Sydenham, Taylors Hill | 419 |

| 8 | 3337 | Melton, Melton West, Toolern Vale, Kurujang | 387 |

| 9 | 3810 | Pakenham, Pakenham South, Pakenham Upper, Rythdale | 385 |

| 10 | 3216 | Belmont, Freshwater Creek, Grovedale, Grovedale East, Highton, Marshall, Mount Duneed, Wandana Heights, Waurn Ponds | 369 |

Source: Office of Hon. John Brumby MP, 12 June 2007

Yet for the past thirty years, urban planners and government have pursued a policy of greater density, more flats and townhouses, in higher blocks, and closer to the centre of town. But rather than acting as these urbanists would like them, ordinary people are using up ever increasing amounts of their incomes to buy the kind of house they want.

The effects of higher prices are very significant. For example, if prices are in excess of $50,000 above the levels prevailing without regulatory distortions -- and we believe they are inflated far more than this -- savings on principal and interest on mortgage payments amount to around $6,000 per annum.

For someone on average earnings of $55,000 ($45,000 after tax) that is an increase in real income of 13 per cent. There are very few measures that governments could take that would offer such a lift in real earnings to such a large number of people.

In terms of changing people's preferences (not the job of government in a free society), urban planning has resulted in ever increasing returns to existing property owners and spiralling land prices. In the process it has even failed to produce the planners' goal of increasing density because those already living near the centre have proved adept at stopping meaningful in-fill.

EFFECTS OF EXPENSIVE HOUSING

EFFECT ON PEOPLE

The Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) defines housing stress as households with housing costs at least thirty per cent of gross household income. Extreme stress is said to occur when housing costs consume more than fifty per cent of total income. (3)

Although thirty per cent of income has been popularly adopted as the level which signifies housing stress, such an approach is only applicable to lower income households. (4) Past a certain level of income if people choose to spend more on housing it is at the expense of other discretionary items (such as holidays and new cars) rather than essential expenditure on food or health services. Many higher income households (and some with lower incomes) choose to pay off their mortgages faster by paying above thirty per cent of their income on housing. Even so, increased shares of income have been allocated to housing payments largely due to increased property prices.

Table 1 illustrates the effect of the increases for Melbourne first home buyers. Even before council rates and basic maintenance costs are added to the mortgage costs, new first home buyers would find it very difficult to enter the current market. Put another way, this lack of affordability is the same as having mortgage interest rates at 14.6 per cent, the level in 1991 and double the current rates. Mortgage default rates have been rising and are now at about 50 per week in Victoria (three times the level of 2001). Notwithstanding this, persistence of at least a few first home buyers in entering the market demonstrates the overwhelming preference of some Australians to own their own home at the expense of other expenditure. Even so, the possibilities of ordinary families being able or willing to do this in Melbourne is clearly diminishing.

Table 1: House affordability for first home buyers, Melbourne

| 2003 | 2007 |

| Weekly family mean income | $1,209 | $1,480 |

| Weekly family median income | $986 | $1,242 |

| Mean income | $62,868 | $76,958 |

| Median income | $51,272 | $64,584 |

| Mean after tax | $48,658 | $58,521 |

| Median after tax | $40,541 | $49,306 |

| Median house price | $335,800 | $370,000 |

| First home buyer house price | $285,430 | $314,500 |

| First home buyer mortgage @ 90% | $256,887 | $283,050 |

| Monthly repayments | $1,655 | $2,222 |

| Annual mortgage | $19,862 | $26,667 |

| Mortgage as % of mean income | 41% | 46% |

| Mortgage as % of median income | 49% | 54% |

Source: ABS 6523.0, 2068.0,

Commonwealth Bank Standard Variable Rate, CBA

Victoria and other governments are in danger of creating a class system -- whereas wealthy people can help their own children get a start in the housing market, children of poorer parents become marginalised -- unlike in the pre-planning restraint era, it is increasingly difficult for them to find the means themselves to step onto the real ladder of opportunity. This illustrates how regulatory measures can have unintended bad consequences. Goals that might have some broad support in the abstract, for example to create higher density cities, come up against people's preferences and the forced densification leads to higher prices and less development that affects the whole community.

Melbourne's outright home ownership at the last census (5) was 33.1 per cent with 34.6 per cent of households buying their own home, a 5.2 per cent decline in home ownership from the total 72.9 per cent sixteen years earlier. (6) Moreover these gross statistics mask some significant changes in the age profile of homeowners. Evidence of this was found in a study conducted in 2002, which deconstructed the changes in home ownership and found the rates of home ownership by younger people are falling faster than average. (7)

In the age bracket where most people have their children (25-44) not only has there been the greatest fall in home ownership rates there is clear evidence that middle and lower income earners are suffering disproportionately large falls in home ownership.

The choice of renting or buying should always be left to individuals, however what is offensive are policies that result in artificially high prices that make such choices unaffordable. Aside from the utilitarian motive that owning a home provides people with a savings cushion that reduces their future call on others, home ownership gives citizens a property stake in the community. That stake would almost certainly enhance their feeling of shared community, thereby providing benefits to everyone.

One of the reasons young families suffer disproportionately from excessive housing costs is that they are often at the stage in the lifecycle where they rely on one income as one parent stays at home to raise young children. Most Australian women return to the workforce once their children are in school however this is often part-time work and occurs when the costs of raising children are at their peak. It is therefore unsurprising that many couples delay having children until they can get settled in their own home.

EFFECT ON THE STATE'S ECONOMY

The high costs of housing in Australia mean that people have a great deal of their assets tied up in it. This means money is redirected from productive investment and that we need to borrow more and/or face lower economic growth than we could achieve.

Regulatory measures that push up the cost of housing reduce the size of the supplying industries. Based on historic levels of new home building, we would see a house building industry maybe 50 per cent larger than at present with prices attuned to the underlying costs and demand.

Reducing costs like this not only relieves the costs of people in the area but acts as a magnet for others. Research in low housing costs in US cities demonstrates that those like Houston, Atlanta and Dallas have enjoyed far greater growth as a result of their increased affordability than other cities. (8) Melbourne can achieve similar outcomes and needs to improve its competitiveness as a source of labour supply and a commercial hub.

Table 2: Home ownership, Melbourne

| Age | 1996 (%) | Change from 1986 |

| 15-24 | 22.2 | -4.4 |

| 25-44 | 63.1 | -6.1 |

| 45-64 | 80.5 | -2.0 |

| 65+ | 79.4 | -1.0 |

| All | 69.8 | -3.0 |

Source: Judith Yates, "Housing Implications of Social, Spatial and Structural Change", Final Report 23, (Sydney: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, July 2002)

WHY HOUSING IS TOO EXPENSIVE

SUMMARISING THE COST COMPONENTS

There are four components of the cost of new houses:

- the virgin land itself

- preparation of the land and its infrastructure

- the house itself

- taxation

Land

Government induced restraints, misleadingly called "planning", prevent land from being used for housing. Victoria has no shortage of land -- less than one per cent of the state is urbanised and most of the rest is farm land.

The virgin land in its normal usage as farmland is worth some $5000 per hectare and there are at least ten 600-square-metre blocks per hectare, hence the underlying value of raw land is some $500 per block. There is no shortage of farm-land which around every Australian city vastly exceeds any conceivable demand for urban development. Yet rationing the supply of raw land multiplies its value one hundred-fold. Farmland selling for $5,000 per hectare becomes worth $500,000 once approved for dwellings.

Figure 2: Land preparation costs

| Nature of cost | Cost per allotment |

Civil works construction costs including:

Establishment & Disestablishment

Sedimentation Control Works

Allotment filling

Road Formation works

Roads, pavements & gutters

Hot-mix seal coat

Stormwater drainage works

Sewer reticulation

Water reticulation

Common Service Trenching

ETSA/Telstra conduits materials

Survey Certificate

CITB levy | $30,415 |

| Sewer | $2,495 |

| Water Supply | $500 |

| Survey & Engineering | $3,000 |

| Planning, registration, title fees | $110 |

| TOTAL | $36,520 |

Infrastructure

Land preparation and construction costs are pretty similar across Australia. Land can be brought on-stream in a matter of months once an approval is given.

Preparing a piece of land for a housing development is not an expensive process. The following shows costs per allotment in a South Australian development some 50 minutes from the Adelaide CBD. Total costs averaged $36,000 which with selling costs and so on might come to $45,000.

With holding and marketing costs, the former of which are in excess of what they should be as a result of unnecessary delays in approval processes, a cost of $45,000 can be estimated for a below average sized block.

This data demonstrates the fallacy of claims that we must have a greater concentration of housing because preparing infrastructure outside of existing areas is exorbitantly costly. Not only is the preparation of land not vastly expensive, but it is by no means certain that urban renewal is cheaper than building on the fringe, given the fact that all infrastructure in the end needs to be replaced. It is actually cheaper in many cases to start anew rather than tear down and rebuild outdated or decaying infrastructure.

Rarely does infrastructure come in at these sorts of levels. Governments usually require home buyers to pay for many of the additional features (such as provision of open space, regional roads, schools etc.) that previous generations of home buyers received as part of general government provision financed through the general tax base.

House Building Costs

Like infrastructure preparation at the new housing block level, house building is an intensely competitive business. Although regulatory measures have been heaped onto house builders through requirements on energy, water and other features, competition has suppressed new house building costs. The cost of a modest starter home of, say 22 squares, which is larger and better appointed than the average sized new home of thirty years ago, can be obtained from a wide variety of builders at less than $120,000.

Taxes

In the case above, a finished house (excluding fencing and other features not normally part of the package) would be available at $165,000.

Taxes would be additional. These might include some modest local charges for registration, approval, and perhaps land taxes amounting to no more than $5000. On top of this would be GST which in the base case examined would be $17,000. Marketing, sales and administrative costs might amount to $9,000 hence a model new home should be selling at under $200,000.

UNDERLYING COST VERSUS ACTUAL

Although there are villa type units available on the Melbourne fringe at $240,000, a more realistic price for a modest new house is around $300,000 with the median new house weighing in at $330,000.

Based on the foregoing discussion, prices are some $100,000 above the level they would be if there were no regulatory costs and if government taxes and charges were not excessive. The "tax" created by government planning restrictions currently set out in Melbourne 2030 amount to some $50,000. This is compounded by taxes on the phantom value and by other charges for services that are not of value to the consumer.

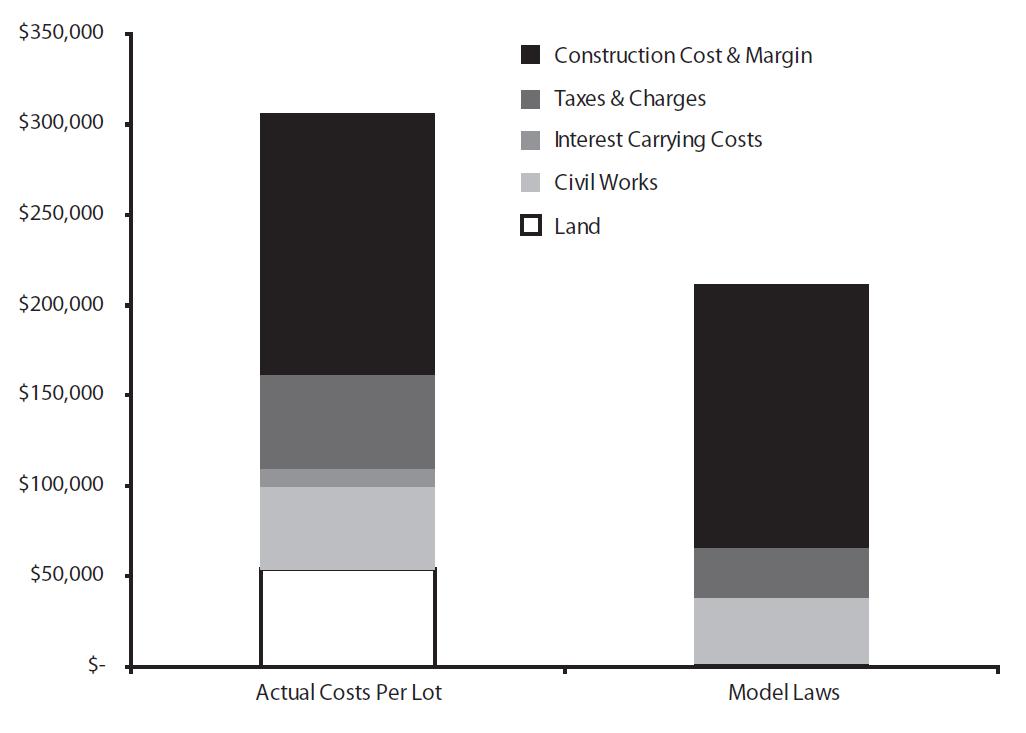

Figure 3 below highlights the difference between actual house and land packages and the cost under a model law regime. The model is not a simplistic removal of all taxes and charges. It demonstrates the flow-through if land starts off being appropriately priced and there are meaningful reductions in stamp duty. Other tax rates such as land tax and the GST are not changed. It should be noted that these costs do not take into consideration the excess costs incorporated in regulatory measures concerning the construction component of houses.

Figure 3: Actual building cost components (Victoria) and model laws Source: Urbis JHD

Source: Urbis JHD

That further component is caused by requiring 5 Star energy efficient buildings, inefficient occupational health and safety red tape and other "hidden" taxes on new home-buyers. These charges can add $23,300. (9) The Master Builders Association of Victoria estimates that new announced OH&S regulations could add up to another $37,000 to new homes, (10) further eroding the dream of home ownership for many families. Even without this new impost, home buyers are spending over 25 per cent of the cost of new house and land packages on excessive charges, taxes and inflated land prices due to government regulation.

The bottom line from Figure 3 is that a house and land package could fall by something of the order of $120,000, a colossal saving for the new home buyer.

EXPLORING THE REASONS FOR HIGH HOUSING COSTS

ATTEMPTING TO MAKE MELBOURNE A HIGHER DENSITY CITY

The modern city is more dispersed because it can be. Jobs are less concentrated, shopping centres more diversified, the share of trips to the centre has fallen from over fifty per cent in the 1940's to ten per cent.

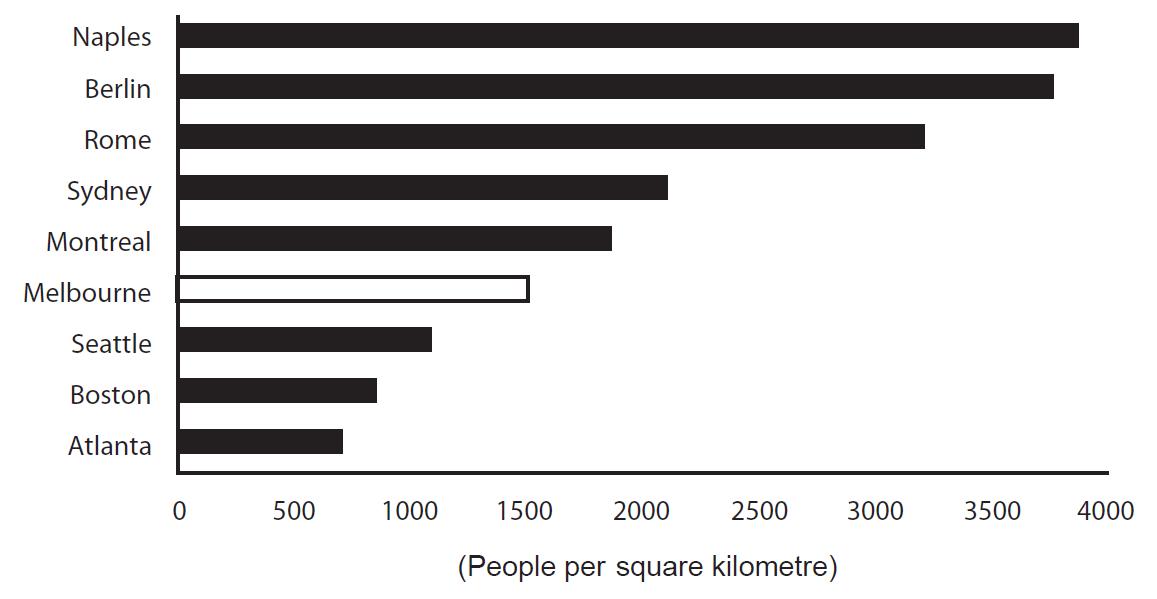

There are common misconceptions that Melbourne's low population density is both exceptional for cities of her size and an unwanted blight. It is comparable with Boston, Seattle, Montreal and virtually every other 2.7 to 3.5 million sized city in the US and Canada.

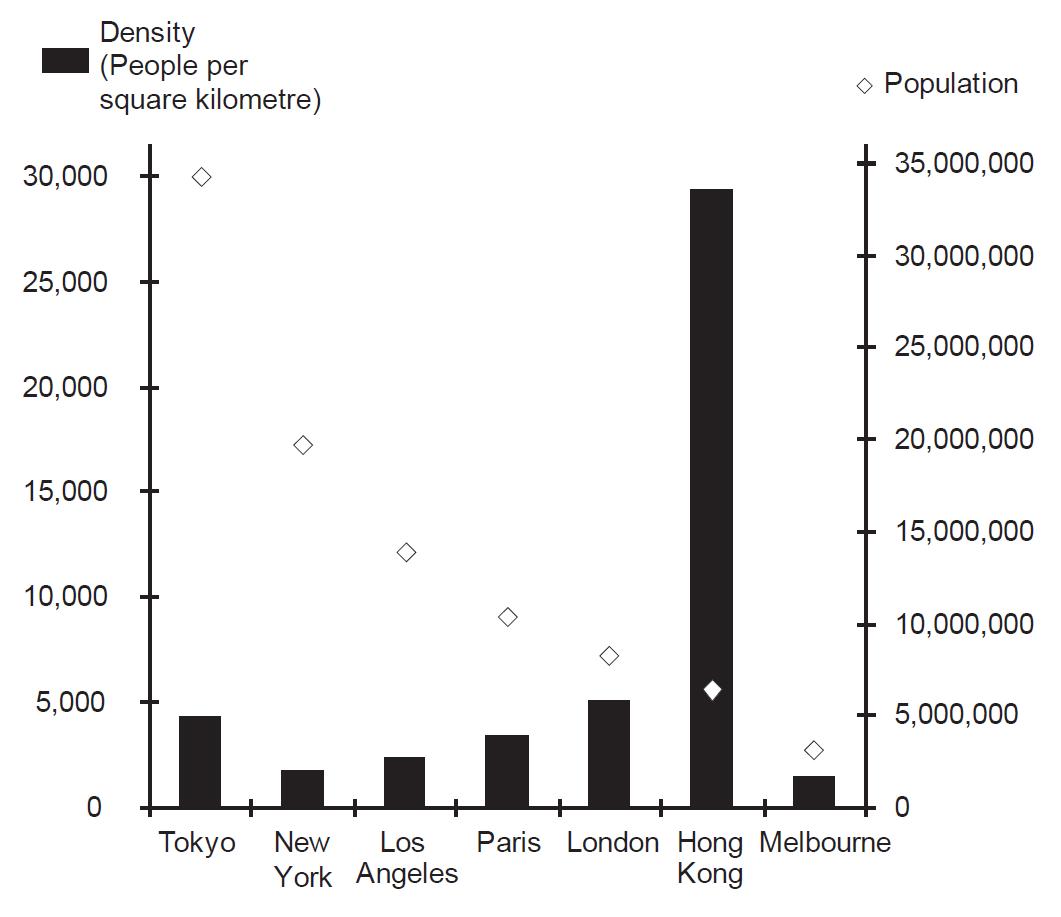

Figure 4 compares Melbourne's density with cities of similar size while Figure 5 and Figure 6 make the comparison with global mega cities and Melbourne's sister cities. Melbourne is on a par with New York and sister city Milan.

Figure 4: Population Density of Selected Similar-Sized Cities Source: Cox, Wendell, "Demographia World Urban Areas (World Agglomeration)," (Belleville, IL: Demographia, March 2007).

Source: Cox, Wendell, "Demographia World Urban Areas (World Agglomeration)," (Belleville, IL: Demographia, March 2007).

Figure 5: Density of Melbourne and global mega-cities Source: Demographia

Source: Demographia

Figure 6: Density of Melbourne and sister cities Source: Demographia

Source: Demographia

Unlike Western Australia and Queensland, Victoria lacks an export resource base and unlike Sydney, Melbourne is not a global tourist destination. Victoria is blessed with plentiful energy and water resources and Melbourne's strengths are her highly educated workforce, great amenity and cultural depth. Melbourne cannot afford to undermine these assets by bureaucratic and ill considered political moves that raise the price of housing artificially. The city's housing land should be among the cheapest in the world and contribute to making the state a standard of living that is surpassed by few other jurisdictions anywhere in the world. On this score it is notable that on the most recent "liveability" index Melbourne has slipped to 17. (11)

The reason behind this shortfall in performance is the scarcity of urban land created by planning rules. This stems from a perversion of the role of the planner which should be to provide for future infrastructure in line with the public's wishes, drawing attention to costs and other considerations. The planner's role is not to dictate preferences. People want to live in their own space and Melbourne is ideally positioned to allow this.

The antagonism of many in the planning fraternity to the choices individuals' make is also indicated by the Victorian planning minister. Mr Madden said in May 2007, "Our increasing affluence has led us to build bigger and bigger houses -- we are suffering from housing obesity". Unsurprisingly, the owners of the large homes found in suburbs such as Caroline Springs took exception to descriptions of their houses as McMansions suffering from housing obesity, noting they chose to build on the edge of the city because that allowed them the size house they wanted at a price they could afford. As Dr Bob Birrell of Monash University commented at the time "the vast majority of those building are actually ... home owners who are upgrading their home from established homes closer into the city". (12)

Thirty years ago these types of homes were being built in Templestowe, ninety years ago in Camberwell. The big houses in Templestowe were ridiculed for incorporating design elements from Greece and Italy or later China, now the big houses in Caroline Springs are mocked as McMansions or for having poor environmental design features. These comments are but the latest in a long line of snobbery over housing. When such attitudes are dressed up as environmental or social concerns and translated in to policy it becomes a triumph of the haves against the aspirations of working people.

Often the sort of lifestyle commentators think people should aspire to bear little relation to their actual dreams. Families want a backyard for the children and the barbeque, they want a comfortable space for the family to watch TV together, and unlike thirty years ago when children sharing a bedroom -- even as teenagers -- was common, these days single rooms are the norm. Moreover, as young people stay at home with their parents longer (partly as a result of high housing prices) many families need additional room to house three or four adults.

With an ageing population it is to be expected that a variation of the granny flat will become common again. After all, even as recently as thirty years ago it was common for widowed mothers to live at least a few years with their adult children's families. More and more families will choose to solve their personal housing dilemmas by multi-generations cohabitating and this will not occur in medium or high density arrangements.

POLICY AIMS OF HIGHER DENSITY NOT MATCHED BY POLICY SETTINGS

Inner city and middle suburban action groups have proved adept in stalling and prohibiting infill and higher density development. As a result, the goal of higher density is not being achieved. It is ironic that often the very people who decry new outer-suburban houses as irresponsible are the same people who prevent significant inner-urban in-fill. In fact it is difficult to find anyone who supports higher density when it involves their own neighbourhood. The end result of reducing new allotments on the periphery and infill nearer the centre is housing shortages which manifest themselves in high house price growth, high rents and high renovation levels.

One way in which pressure groups are effective in restricting infill is by objecting to developments even if they are not directly affected. There will always be a legitimate place for neighbours to complain if they will be overshadowed, inconvenienced or have their property value diminished in some way by new developments. However the State government would go some way to achieving its own policy goals if the grounds of standing were narrowed so that projects cannot be unduly stalled. Even relatively low density infill, say three townhouses on a block, is often blocked or at best massively delayed. With land prices in the inner and middle suburbs being what they are this can effectively make infill development too risky to pursue.

LAND PRICES

All these factors have had a bearing in driving up land prices. In 2004 the Melbourne 2030 Implementation Reference Group identified "the single most important factor influencing housing affordability is the cost of land and it is therefore imperative that land cost pressures are addressed ... Increases in land prices, as a result of constrained supply is a major factor contributing to housing price increases". (13) Disappointingly, Melbourne's planning framework ignores this insight.

The State Government's planning framework, Melbourne 2030, explicitly sets out to reduce the amount of housing development on the edge of the city. It does this in two ways; by restricting growth to five designated growth areas and by the arbitrary creation of an urban growth boundary. It is notable that although the urban growth boundary was only created in 2005 it has already been extended in five directions reinforcing the impression of a poorly thought through concept.

Moreover, while Melbourne 2030 envisages growth in Melbourne's population of one million people and this population growth estimate is repeated in the more recent Victoria in Future 2004, (14) the total land allocated for additional housing in the five designated growth areas only provides for 290,000 people or 118,000 households. By implication, 710,000 additional people will be housed in existing suburbs by building higher density housing such as apartment blocks and terrace houses. This will necessitate a profound change in the way many Melburnians live and will require more radical changes to the current planning schemes to override the current level of opposition to infill.

Yet so far the Victorian Government has only concentrated on one side of the policy equation to achieve its goal of greater infill. Although the planning scheme effectively restricts periphery growth, to date there has not been the same concentration on freeing up infill sites, particularly large infill sites, for redevelopment.

In recent weeks Minister Madden has made some encouraging comments (15) that may go some way to creating planning decisions based on clearly set out rules and decided by panels not subject to the rampant "nimbyism" many councils contend with and sometimes foster.

Unsurprisingly, because only supply on the edge has been restricted without a corresponding increase of infill, the result has been in land prices outstripping inflation and the growth in building costs. As Figure 7 shows, until recently housing building costs have remained relatively stable over the past 30 years but land prices have more than tripled. In recent years the added taxation, building code and other charges have caused the housing component to shoot up but despite this the growth in land prices still outstrips the growth in building costs as Table 3 shows.

Table 3: New land and house package costs, Melbourne

| 1973 | 1983 | 1993 | 2006 | Price increase

multiple

1973-2006 |

| Land | $50,690 | $38,628 | $67,763 | $133,772 | 2.6 |

| House | $102,849 | $85,568 | $103,719 | $195,815 | 1.9 |

| Total | $153,539 | $124,196 | $171,482 | $329,587 | 2.1 |

Source: UDIA

Figure 7: Real Melbourne land and building costs Source: UDIA

Source: UDIA

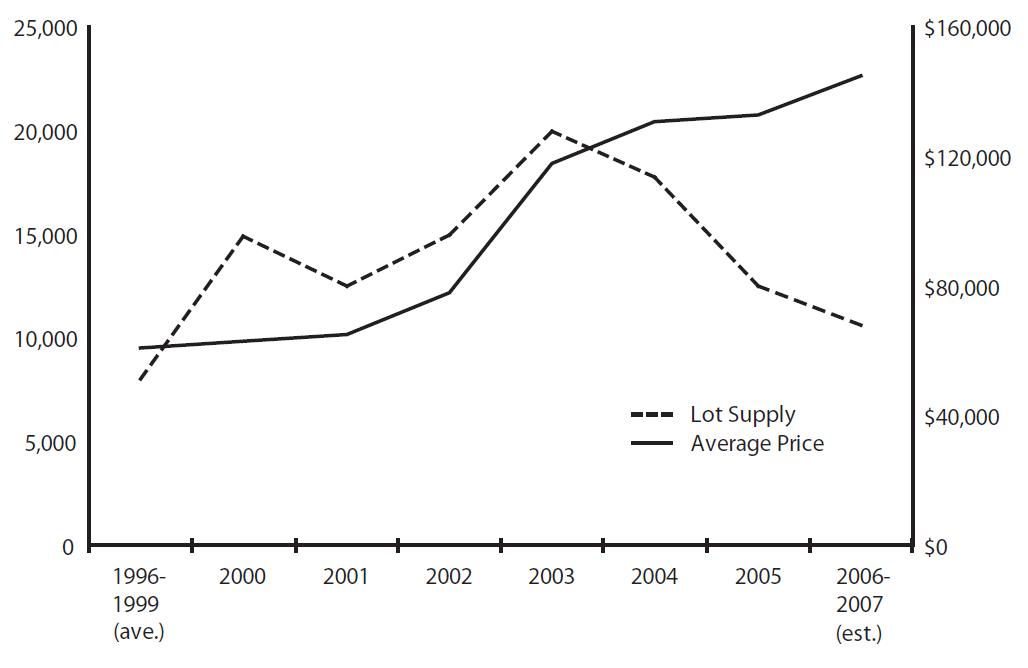

As Figure 8 makes clear, the increase in the cost of land in Melbourne is directly related to the supply. Since 2003 the supply of housing lots ready to be built on has declined by 47 per cent to just over 10,000 per year. This restriction in the supply of new housing lots has had a predictable effect, as land costs are up 23 per cent in three years.

Figure 8: Lot supply and average price, Melbourne Source: UDIA

Source: UDIA

Land prices are high not because it is either expensive or time-costly to prepare land for development. Land can be brought on-stream in a matter of months once an approval is given. Preparing a piece of land for a housing development is not an expensive or long process.

Sometimes it is claimed there is an abundance of land available but that developers are hoarding it. This is not credible. There are dozens of developers and it would need collusion on a massive scale for them to drive up prices.

The fact is that developers are planning their businesses years ahead and need a land inventory. They also face the problem of slow approval processes including sequential approval processes that can take a decade between land release and the ability to actually build on the land. Governments should be able to do something about this, as much of the delay is caused by the accumulation of heritage, environment and other laws that they have introduced.

In any event, if the problem is a reluctance of developers to prepare and build on land that has been released, that is easily resolved by releasing more land. There is no land shortage -- less than one per cent of Victorian land is urbanised, far less than the US areas where land releases are keeping pace with demand. If the government were to release more land for development an average sized block on the fringe of Melbourne would cost about $60,000. This compares with current costs of around $145,000.

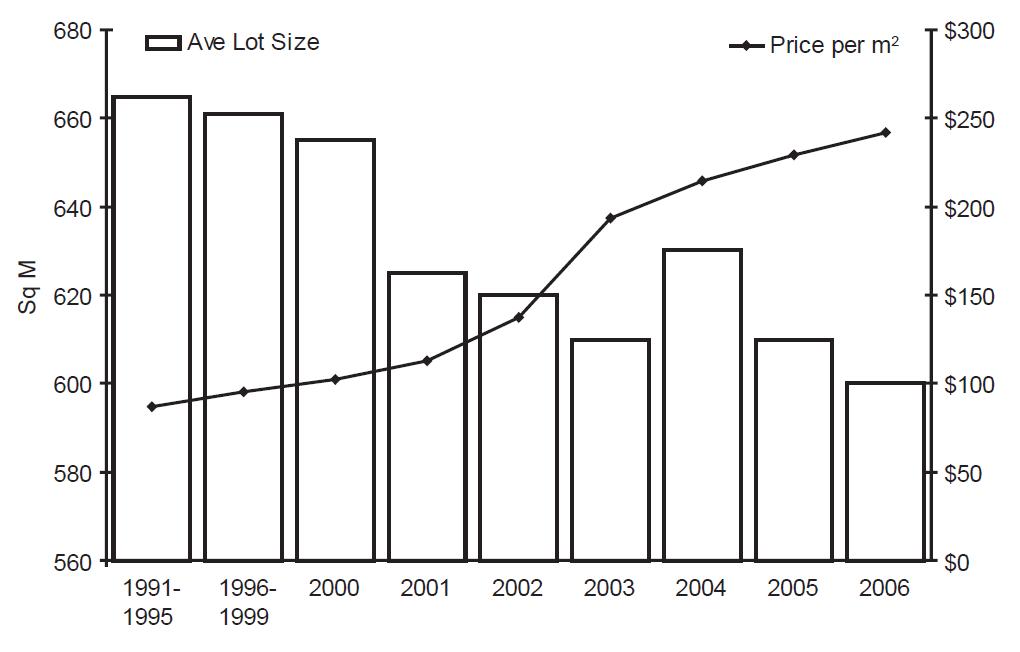

A QUARTER ACRE BLOCK IS A FOND MEMORY

Melbourne's average block sizes are declining from around 800 square metres (0.2 of an acre) 20 years ago, and comparable in size to the suburban areas of many US cities, to around 600 square metres today. (16)

The reduction in house block size is unlikely to be driven by consumer preference. New house sizes have been increasing as block size shrinks, leading to the phenomena disparagingly called McMansions. Instead, the reduction in house block size is much more likely related to the exorbitant cost of development land. Families buying these new house and land packages just cannot afford the size blocks their parents could and the continuing preference for more housing space per person is leading to larger houses being placed on smaller blocks. Recent comment from developers has noted house sizes are now falling as people decide they can live without a separate dining room or the fourth bedroom. Again, this is unlikely to be an expression of unbounded consumer preference. Home builders having already shrunk their block size by 30 per cent as land prices have exploded, and are now lowering their expectations of what kind of house they can build and still be able to afford it.

As a recent UK report into planning notes densification comes at a cost, the cost of frustrating the clear preference of most people to live in detached housing rather than flats or other housing options. Furthermore "densification can also make the best use of available land, but there are limits to how far this can go. Although in some urban areas it is possible to build at very high densities, this may be less acceptable elsewhere. The savings of land which come from building at 50, rather than 40 dwellings per hectare are smaller than those from building at 30 rather than 20 per hectare". (17)

In Melbourne, like the rest of Australia, people have over long periods of time expressed a clear preference for lower density living. The Australian lifestyle has also been a key draw card for the large waves of immigration by people who have achieved their dreams by building houses that reflect their heritage in suburbs in all major cities. There are some 1.3 million British born emigrants resident in Australia and according to research by the Institute for Policy Research (18) a major reason for this outflow is the exorbitant price of houses in the UK.

Figure 9: Lot sizes and price, Melbourne Source: UDIA

Source: UDIA

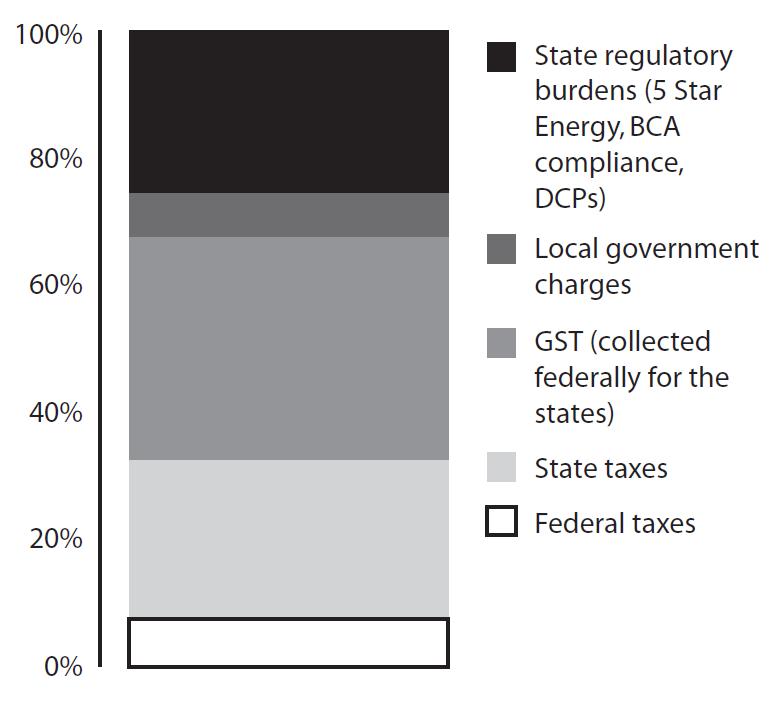

TAXES & CHARGES

Taxes and charges fall particularly heavily on new housing. While some taxes, such as the GST, are not industry specific, most fall more heavily on building construction than other industries. Most taxes levied on housing are State taxes or taxes collected for the States. On a typical $370,000 house and land package, total taxes and charges are over $60,000. Other government related costs such as development contribution plan charges (DCPs), energy efficiency mandates and BCA compliance add a further $23,000. Of the total government costs of $84,000, 53 per cent flows to the state government, about ten per cent to the Federal government, 16 per cent to local government and 20 per cent are additional costs that would otherwise not be borne by builders if not for the regulations. So, in all, a new home buyer pays 30 per cent more than the untaxed cost of the land and building once all these imposts are included.

Figure 10: Taxes and charges in new housing developments, Victoria Source: Property Council, State & Federal Tax Rates

Source: Property Council, State & Federal Tax Rates

TAXATION AND POSITIONAL SCARCITY

It is sometimes difficult to determine whether specific taxes add to prices or are absorbed by the supply chain.

Taxes that comprise general charges like GST, stamp duty and land tax, are in the main, a further impost that the consumer pays. In this respect, the taxes boost the value of existing houses to the degree that the impost on these was originally lower.

Some other taxes probably get partially absorbed by the suppliers. This is likely to occur where government restrictions in land availability have created a scarcity and boosted land prices. In Sydney local and state wide specific infrastructure charges offer no value to the new house owner but are simply a convenient way of clawing back to the government some of the regulatory tax created by their policies in restricting land supply. Such charges in Sydney amount to $42,000-$83,000 per block. Thankfully Melbourne does not engage in price gouging to anywhere near the extent of Sydney, however infrastructure charges for items not directly related to the homes being built can still be of the order of $8,000 per block. In Melbourne these charges are likely to continue to increase as long as land is rationed. This is because a substantial proportion of the charge is for open space and this is paid at the rate of five per cent of land value. (19)

The discussion of these costs should not overlook that some land and houses that are positioned well are likely to be more costly than others. And with higher levels of discretionary income, one might hypothesise that the more desirable places will see higher than average price increases and in fact this is the case. As Table 4 shows, the most expensive housing is under 10km from the city and has shown the greatest dollar increase over the past decade.

Table 4: Median metropolitan house prices by distance from city centre, Melbourne

Distance from

city centre (km) | Median house price (nominal) |

| 1996 | 2006 | % increase |

| 5 | $231,653 | $646,450 | 179.06 |

| 10 | $255,120 | $724,996 | 184.18 |

| 15 | $155,714 | $418,709 | 168.90 |

| 20 | $133,051 | $349,421 | 162.62 |

| 25 | $157,246 | $335,133 | 113.13 |

| 30 | $134,189 | $321,848 | 139.85 |

| 35 | $121,756 | $302,726 | 148.63 |

| 40 | $111,404 | $308,036 | 176.50 |

| 40+ | $111,554 | $318,703 | 185.69 |

Source: SGS Economics and Planning

Even cities with no planning restraints like Houston have their $2 million houses. Doubtless, whatever is done about the availability of land on the fringe of Melbourne would have little effect on property prices in places such as Albert Park, Richmond or Williamstown. It would be an exceptional person who if given the opportunity to live in a same-sized house in either Tarneit or Toorak would choose Tarneit: the services, expectation of appreciation, proximity and amenity of Toorak outweigh Tarneit.

An increase in the supply of land will over time cause existing houses in neighbouring suburbs to adjust to the lower prices. Inner and middle suburbs are unlikely to change as the characteristics that make them desirable will not have changed by making periphery land cheaper. However, an adjustment process to transition to a freer supply of land will be necessary; people have made investment decisions assuming land rationing and this will take time to be unwound.

But the main problem is that artificially induced scarcity is boosting prices. Compared to previous years, the first home buyer on average in Australia faces a median house price at 6.6 times median household income levels. For decades this ratio was 3:1. Returning to that level is both possible and desirable. It is made possible by the continued underlying efficiency of the building and land preparation industries and by the almost limitless supplies of land that can be easily transformed to urban land and still leave no shortage for amenity and commercial farming.

BUILDING COST IMPOSTS

Building costs have remained stable in spite of regulatory impositions, especially those concerning energy where recent 5 Star measures according to the industry increased cost by some $10,000 per home (20) and up to $30,000 in some cases. (21) Other additional building regulations amount to a further $5,000 per home. The increased imposts placed on new housing raises its costs. As a result the value of existing housing also increases even though existing houses do not pay any of the cost.

These additional charges are doubly unfair. Existing home owners gain a benefit from additional costs on new houses which they don't have to pay for, while those trying to buy a home are forced to pay additional costs that previous generations of home owners never had to. Approximately 94 per cent of Melbourne's buildings were built before 4 Star ratings were mandated in July 2004 and the vast bulk of energy use is by existing homes.

As Brian Welch of the Master Builders Association of Victoria notes, "There is no point having sustainable housing that no one can afford". (22) For sure, good design can ameliorate the use of some air-conditioning, but the most effective way to reduce its use is to make energy more expensive.

By far the fairest policy the government could pursue if the goal is to reduce energy and water consumption is to make them more expensive across the board.

Environmental regulations are not the only building cost imposts being capitalised in new housing projects. Proposed amendments to OHS regulations represent "a potential cost increase of between 4.85 per cent to 18.5 per cent to the cost of building a new $200,000 home. This translates into additional monthly repayments of between $78 and $297 on a $200,000 loan and an increase in interest over the loan of $9,121 to $34,122". (23) These new regulations, if passed, will fall particularly heavily on small building firms due to the increase in compliance with no demonstrated improvement in OHS on building sites. Regulation such as this is not costless and will be passed on to new home buyers.

SUBURBAN DREAMS

Within current planning discourses a number of orthodoxies reign. Together these orthodoxies seek to build a comprehensive case in favour of urban infill and increased density. However, the majority of urban Victorians, like their counterparts in other Australian cities, choose to live in suburbia. Moreover, for many people, the great Australian dream is still to own their own home, of their own specifications, surrounded by families doing the same thing.

Underlying all criticisms of sprawl are two paradigms that need to be challenged. First is population growth. Melbourne will continue to grow for many years, probably for the foreseeable future as continued immigration makes up for an ageing population and low birth rate. Population growth is an important driver of economic growth and the State Government is to be commended for its continuing support of strong population growth. However, some opponents of suburbia are anti-population growth, views often driven by radical environmentalism. If opponents of urban growth are really anti-immigration, let them make that argument, not hide behind criticism of sprawl.

The second set of arguments are anti-economic growth arguments, sometimes allied to anti-population growth beliefs but most often manifested these days as responses to global warming. Policy responses to global warming are extremely complex to fashion if they are not to fall disproportionately on the poor. Criticisms of sprawl on energy use grounds tend to pursue a radical path in terms of energy use (solar), water use (restricted and recycled) and transport use (public transport) which are much easier to mandate for new housing despite the fact most people live in existing housing. Again, it is much easier for those who can afford to live in the inner suburbs to pontificate about the wastefulness of those building detached housing further out when the existing housing would not meet any of the energy and water-saving measures forced on new home builders.

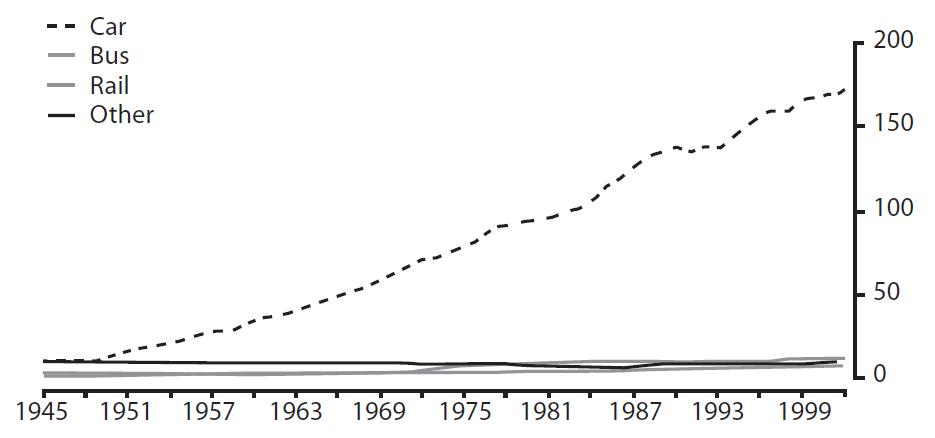

MYTHS ABOUT PUBLIC TRANSPORT

There is a view often put that more people should take public transport, particularly to commute to work in the CBD. For single destination, long-haul trips heavy rail is an excellent means of moving large groups of people. Recent increases in rail patronage and consequent peak-hour overcrowding are testament to the fact city commuters will abandon their cars for public transport in some circumstances. However, only 15 per cent of total employment is in the central business districts (24) and this figure continues to fall. Public transport systems designed around getting people to work no longer fit the patterns of work with more people working across town from where they live. Less than 10 per cent of work trips in Melbourne are by public transport and notwithstanding ambitious statements by government spokesmen, this share is most unlikely to increase unless punitive and efficiency destroying measures are introduced to force people to abandon car use.

In 2000 private road vehicles represented about 91 per cent of city passenger transport in Melbourne. Urban public transport is a minor component of city transport and has been for many years (see Figure 11).

Figure 11: Urban passenger transport trips, Australia Source: Bureau of Transport Economics, "Forecasting Light Vehicle Traffic", Working Paper 38, (Canberra: BTRE, October 1998).

Source: Bureau of Transport Economics, "Forecasting Light Vehicle Traffic", Working Paper 38, (Canberra: BTRE, October 1998).

No amount of money poured into public transport will make most people use it. Even if free it is not convenient for people who want to go across town, who have the weekly food shopping, who have babies and young children with them. Furthermore, despite the smug superiority expressed by some inner-city residents for their car-less lifestyle, car ownership is directly correlated with affluence and the personal freedom that comes from having one's own transport. Policies that make car ownership unaffordable fall more heavily on poorer people.

Over the past thirty years the car has proven to be the preferred mode of transport except in extremely dense cities such as Hong Kong and Tokyo. Melbourne can never emulate the high rise density of Hong Kong and therefore can never match the densities needed to run a mass transit system that people actually prefer to use. It is unrealistic to attempt to instil an alien mass transit ethic on fundamentally suburban communities, the result will be higher public transport subsidies not higher usage.

EXISTING INFRASTRUCTURE IS OFTEN AT CAPACITY

An argument put in favour of increasing density in established areas is that this better uses the existing infrastructure -- roads, sewerage, public transport etc. However, this line of thinking, is frequently stymied by the power of existing homeowners in established suburbs who will not accept increased density in their area, arguing it will destroy the character of the area. The result is the infill plans of the planners are not fulfilled and housing pressures remain.

There is a false assumption underlying the infrastructure utilisation orthodoxy. The false assumption is that increasing density in the centre will result in better utilisation of services and utilities. In some cases, such as inner city roads, these are at capacity already. In others, such as sewers, inner city municipalities have persistently skimped on maintenance and upgrades because as their population densities declined it has been cost effective to let those services slowly decay. In some cases the costs of upgrading them for higher density is well beyond the costs of new sewers on the urban fringe. As an example of this, high speed telecommunications needs optic fibre to the home, easily and cheaply added to new developments but very expensively to existing housing.

Even if it were to be cheaper to provide services to infill than greenfields development, the clear response in that circumstance is to fully and properly cost the unavoidable infrastructure costs and add these to the development. Open and transparent costs allow potential buyers to effectively weigh up whether they are prepared to pay those costs.

Figure 12: Population of Melbourne & Melbourne local government area Source: ABS 2006 Census

Source: ABS 2006 Census

USING ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERNS TO DICTATE CHOICES

The environmental orthodoxy argues households with large houses on the periphery use more energy than compact houses near the centre. Unsurprisingly the data tends to support the assertion that if the energy costs of a large house is compared with that of a small inner-city terrace.

Similarly the argument is put that residents on the periphery have higher car use. More car use causes higher greenhouse gases. This is a bad thing. As discussed in the transport section above, even making public transport free and accessible will not make most people use it. And the arguments about discriminating against poorer members of society apply with transport policy as well. As a recent research for the Brotherhood of St Laurence finds, carbon taxes disproportionately fall on poorer members of society. (25) Higher petrol prices caused either by taxation or higher global prices fall more heavily on poorer members of society who live further away from the expensive centre.

Pertinent to this argument is data and analysis by the Australian Conservation Foundation (26) which shows the carbon footprint is greatest at the centre of Melbourne. For example the per person emissions of Yarra 26.05 tonnes, Port Philip 26.88 tonnes and Boroondara 26.47 tonnes compare unfavourably with Melton 16.87 tonnes, Cardinia 16.63 tonnes and Whittlesea 17.42 tonnes.

The environmental arguments are persuasive because they fit nicely with existing aesthetic prejudices against the sort of new housing being built on the edge. It is very easy to translate snobbery against those who would rather buy a large plasma TV rather than a library of books or those who build a house with a home theatre rather than a dining room, into prescriptions to change those choices via taxes and regulation in the name of the environment.

SHRINKING HOUSEHOLD SIZE IS NOT SHRINKING HOUSE SIZE

The planning minister has suggested, "Melbourne will need 620,000 additional dwellings by 2030, 90 per cent of them one or two-person households". (27) A conclusion often drawn from this is that Melbourne will need additional flats and units to house the growth in smaller households. Such a conclusion is often premised on the notion that "as household size declines housing size should also decline and people who do not adjust their living space in light of the number of people in the household are underutilising the housing stock". (28)

Table 5: Change in % of types of dwellings in selected inner Melbourne areas

| Houses | 1-2 story

flats &

units | 3 or more

story flats |

| Banyule | -2 | 4 | 0 |

| Bayside | -4 | 5 | 0 |

| Boroondara | -2 | 3 | 1 |

| Brimbank | -7 | 10 | 0 |

| Glen Eira | -2 | 4 | 1 |

| Manningham | -5 | 7 | 0 |

| Maribyrnong | -4 | 6 | 0 |

| Moonee Valley | -2 | 5 | 0 |

| Stonnington | -0 | 1 | 2 |

| Whitehorse | -3 | 5 | 0 |

| Yarra | -2 | 3 | 3 |

Source: ABS 2006 Census

Household size has been declining for over 40 years yet until recently house size has been growing as all households exercise their preference for larger per person living spaces. The notion that "empty nesters", child free couples and singles somehow all prefer to live in new high rise inner urban apartment blocks has not been borne out by the evidence. (29) The occupants of the new apartment blocks are overwhelmingly young people, often students and recent graduates moving out of their childhood home. Relatively few families with children or people over thirty are populating the revitalised inner city. (30)

Over the past five years the building out of Docklands and Southbank has increased density in the City of Melbourne, in which is found 66 per cent of all apartment blocks greater than three stories in greater Melbourne. Docklands and Southbank account for 46 per cent of that.

The Victorian Department of Sustainability and Environment website describes, most families whose children have left home prefer to buy their retirement home in the same area they raised their children. This is not surprising. It's where their friends are, they know where the services and shops are and importantly it is tied up with their self identity after having invested many years into the community in which they live. There is therefore demand for higher density infill in existing suburbs as existing residents move through their life cycle.

This new housing will be a mix of apartments and townhouses and of clearly greater density than existing detached housing in older suburbs. It is therefore ironic that the most vociferous opponents of just this type of housing are the existing residents.

SAVE OUR SUBURBS MEMBERS -- WHERE WILL THEY LIVE IN RETIREMENT?

The planning activists group Save Our Suburbs (SOS) has been a thorn in the side of governments since the mid 1990's. Membership of the organisation is largely concentrated in the inner suburbs, particularly in the most expensive areas of Melbourne. The group is opposed to what they see as forced densification of their neighbourhoods.

However, an analysis of household formation in the suburbs covered by SOS shows that over the past decade there has been a small decline in stand-alone houses -- averaging 3.2per cent -- in favour of a move towards townhouses and units of one and two stories. Very few blocks of flats of three stories or more have been built, in fact across the eleven local government areas surveyed, more new detached houses (6,821) than flats over three stories (3,807) have been built in the past decade.

Like the rest of Melbourne these suburbs are still predominately characterised by stand alone houses (67per cent) yet the age profile of the residents is above that of greater Melbourne. There are a greater proportion of single people and couples living in stand-alone houses than in other areas. One reason for this may well be the lack of suitable quality flats, townhouses and units for those empty-nesters who want to stay in the same area but no longer want or need the expense and upkeep of a large family home.

These inner suburbs are the prime locations for additional infill as they are well serviced by public transport, have high levels of services and amenity and all have substantial areas -- often former industrial areas -- where projects of significant scale could be built. Yet far too often nondescript buildings end up with heritage overlays, residents from streets away complain there won't be enough parking (never mind that often their own homes have no off-street parking), and spurious appeals are made about the character of the suburb being detached housing not apartments. So the big projects are rarely attempted, particularly when developers see councils and even the State Government caving in to noisy minorities on projects like the Abbotsford Convent site.

Unlike State and Federal governments who make policy but have their application of policy interpreted by the courts, local councils make the planning framework and then assess development projects against their own framework. Yet often councils cave in to opposition pressure and reject applications that meet their own planning frameworks. As elected representatives, councillors have a clear role in setting their area's planning framework, including overlays which restrict development in some areas. The assessment of individual planning applications should then be conducted by planning experts in line with the set policies. At present far too many planning decisions are made for political reasons and the process is far too open to corruption.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The overwhelming reason housing is too expensive for first home buyers and ordinary middle income families is because land is massively overpriced. This can be fixed relatively easily; by easing the planning controls and other cost imposts that restrict the supply of land for housing.

Despite thirty years of a planning orthodoxy designed to increase density, home buyers have consistently frustrated the designs of planners and governments to force them into high rise apartments. Overwhelmingly families, particularly as they begin to have children, want to live in low density, residential neighbourhoods. Market forces if left to their own devices will ensure these are serviced by convenient shopping centres. The great Australian dream remains a detached house. When denied this choice or government regulations overprice it, people opt for a reduced block size. Now, an ever growing number are not able to buy at all and remain in the rental market.

Government can fix the housing crisis and the way to do so for Melbourne is clear.

- Abolish the urban growth boundary and allow the release of significantly more land on the periphery for housing.

- Set annual targets for infill construction in line with the assumptions of Melbourne 2030. Introduce planning panels or other mechanisms to facilitate the approval of infill projects of sufficient scale to match the infill targets in Melbourne 2030.

- Reduce exorbitant taxes and charges, particularly unfair levies for general services which have traditionally been provided by the State out of general revenue.

- Remove excessive environmental and other regulatory imposts. Refrain from enacting even more of these prescriptive rules such as even higher Star ratings, new occupational health and safety laws.

Implementation of the first recommendation in a robust manner will reduce the cost of land and have the greatest impact on affordability for home buyers of detached housing. Implementation of the second recommendation is also supply related and will therefore also improve affordability by reducing the price of apartments in more inner locations. Improving equity is the basis for recommendations three and four. The levies, taxes and building regulations are costs borne by new home buyers as developers largely pass them on in higher house prices. Buyers of existing housing do not pay these charges despite generally buying more expensive housing. It is particularly inequitable that home buyers in new suburbs should bear the cost of services and amenities that were provided by general revenue to older suburbs.

It is not the right of government to dictate to the people how they should live. It is their duty to remove blockages to people's pursuit of their own versions of happiness not to create barriers to this.

REFERENCES

1. Wendell Cox and Hugh Pavletich, "3rd Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey: 2007", (Belleville, IL: 2007).

2. Australian Bureau of Statistics, "Cat. No. 2068.0 -- 2006 Census", (ABS, 2007).

3. Judith Yates, "Housing Implications of Social, Spatial and Structural Change", (Sydney: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, 2002).

4. See ABS Cat. No. 4130.0.55.001 -- Housing Occupancy and Costs, Australia, 2000-01 for an explanation of why only households in the bottom 40 percent of income definition should be used to measure housing stress using the thirty percent rule.

5. Australian Bureau of Statistics, "Cat. No. 2068.0 -- 2006 Census".

6. Yates, "Housing Implications of Social, Spatial and Structural Change".

7. ibid.

8. See Glaeser E. et al, "Urban Growth and Housing Supply", Harvard 2005

9. Urbis JHD, "Residential Development Cost Benchmarking Study", (Brisbane: Residential Development Council, 2006).

10. Master Builders Association of Victoria. "New Regs Biggest Blow to Housing Affordability in a Decade", news release, June 5, 2007.

11. Mercer Study

12. Samantha Donovan, "Minister in Hot Water over 'Obese House' Call", The World Today on ABC Local Radio, 17 May 2007.

13. Melbourne 2030 Implementation Reference Group, "Priority Implementation Issues", ed. Department of Sustainability and Environment (2004), p. 20.

14. Department of Sustainability and Environment, "Victoria in Future 2004: Victorian State Government Population and Household Projections 2001-2031", (Melbourne: Victorian State Government, 2004).

15. "A Planning Devolution That Should Be Debated", The Age, July 18 2007.

16. David Poole, "The 2006 UDIA State of the Land", (Epping, NSW: Urban Development Institute of Australia, 2006).

17. Kate Barker, "Barker Review of Land Use Planning", (Norwich: HMSO Treasury, 2006).

18. http://www.ippr.org.uk/pressreleases/?id=2479

19. Urbis JHD, "National Housing Infrastructure Costs Study", (Brisbane: Residential Development Council, 2006).

20. ———, "Residential Development Cost Benchmarking Study".

21. Brian Welch, "Sustainability Burden Needs to Be Shared", The Age, July 5th 2007.

22. ibid.

23. Master Builders Association of Victoria, "Submission on the Proposed Occupational Health and Safety Regulations 2007", (MBAV, 2007).

24. Richard J. Wood, The Tragedy of Planning (Toowoomba, 2006).

25. Liz Minchin, "Carbon Footprint of Rich Twice That of Poor", The Age, June 16 2007.

26. http://www.acfonline.org.au/custom_atlas/index.html

27. Justin Madden, "Housing for All While Trying to Curb the Dreaded Sprawl", The Age, July 9 2007.

28. Batten, "The Mismatch Argument: The Construction of a Housing Orthodoxy in Australia".

29. Gary V. Engelhardt, "Housing Trends among Baby Boomers", (Washington, D.C.: Research Institute for Housing America, 2006).

30. Australian Bureau of Statistics, "Cat. No. 2068.0 -- 2006 Census".