Submission

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY

Our approach to the Review

The Energy Market Review Issues Paper sets out six priority issues. Three of these (1) are not addressed in this submission, which concentrates on

- Identifying any impediments to the full realisation of the benefits of energy market reform;

- Identifying strategic directions for further energy market reform;

- Examining regulatory approaches that effectively balance incentives for new supply investment, demand responses and benefits to consumers;

In addressing these matters we wish to offer information that:

- stresses the importance of private ownership and secure property rights in promoting greater efficiency;

- examines how to ease the tension between competitive prices and minimal regulation on vertically non-integrated or effectively ring fenced companies;

- explores how to facilitate access pricing regulation that avoids excessive intrusion and inflexibilities, reduces the current enormous paperburden, and allows businesses greater certainty on which to invest and grow;

- provides advice on the appropriate principles for establishing pricing regimes for regulated services; and

- would facilitate a greater consistency of treatment of regulated facilities across Australia.

The electricity and gas industries

Electricity and gas are vital cogs in modern economies with an importance that is considerably understated merely by measuring their share in GDP (three per cent or so) the industry comprises. Without power and light from electricity and gas few of our daily activities would be possible. While gas and electricity are in competition with each other, gas is a significant fuel for electricity and many energy businesses have interests in both.

Aside from matters stemming from their ubiquity within the economy the industries' composition also creates policy issues. The industries' four branches: production, transmission, distribution and retailing, are interdependent. Until the last decade or so they were usually integrated, although natural gas production has normally been separate from its transport and retailing. The industries' disaggregation has been universally accepted as the best contemporary means of bringing greater efficiency. This allows for competition to be more active within the industries. As with all structural arrangements, these may not be optimal for all situations and, indeed, some retailers have acquired some generation.

Under the present policy framework, generation and retailing are treated as market-driven contestable sub-industries and transmission and retailing as natural monopolies that require some regulatory control. The regulatory/competitive dichotomy is, of course, not hard and fast. Some -- primarily small isolated -- regions may find it difficult to ensure sufficient competition in generation or retailing. And there are developments, especially in transmission, which are eroding the previous monopoly over supply.

The interface of a regulated with deregulated parts of the industry poses considerable risks to efficiency and commercial viability.. Regulated output prices using inputs with deregulated prices can, as has been seen, quickly bring ruinous cost squeezes. More commonly, unless the regulation is highly attuned to the true market position, it can lead to a gradual erosion of the incentives that are essential to drive efficiency in any industry. This applies especially to industries with private ownership.

In this latter respect, there is also now a widespread, though not unanimous view that private ownership in energy industries is superior to public ownership. We have been and remain a major participant in promoting the merits of privatisation

Private ownership itself adds another dimension to the regulatory agenda. An industry that is privately owned, even in part, cannot internalise its transactions in the way that is possible within a government integrated monopoly. This brings an illumination of costs and efficiencies that was previously hidden, facilitating means of promoting efficiency.

1. THE IMPORTANCE OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS

For much of the twentieth century, public ownership and central planning enjoyed wide support as the best means of promoting efficiency. There is now no reputable body of opinion that maintains such a view.

There is impressive empirical evidence gathered through hundreds of studies by the World Bank to demonstrate the greater efficiency of private ownership. This is notwithstanding examples of successful government businesses. Indeed, in the Australian energy industries there have been some aggressive marketing moves by some publicly owned retailers, notably Energex. Similarly, energyAustralia has been highly innovative in seeking to ensure new domestic customers installing air-conditioning are charged their true costs.

Although government owned businesses are capable of considerable efficiencies, in the final analysis they suffer from four disabilities that tend to weaken their performance disciplines over the longer term. These are:

- The lack of a market for the firm itself if others perceive its management is underperforming. It is not possible for a rival to mount a take-over (or, unless the state privatises) for the owners to voluntarily leave the field to a different management that might perform better.

- The ownership by the state means some political influence is almost certain to be wielded, eventually perhaps in the form of tariff setting, perhaps in requiring the business to operate using the government's preferred form of labour relations.

- The difficulties of motivating the management with a comprehensive profit related stake in the business

- The lack of profit maximising shareholders who have alternative venues for their funds.

Low cost energy is one of Australia's key natural advantages, even if, as during the much vaunted resources boom of the 1970s, the advantage has from time to time been over-stated. However, comparisons between Australian and international electricity and gas supply industries conducted during the 1980s demonstrated that our industries were lagging in competitiveness. Poor management, political interference and union controls had left the industries with chronic over-manning, excessive development, and prices that failed to match costs.

All states, with the partial exception of Queensland shared in this malaise, but it was in Victoria that the problems were deepest seated. Different studies by Victorian Government bodies (2) established the nature of the weakness and the Productivity Commission's predecessor body, the Industry Commission (IC) documented this more comprehensively. (3)

The Commission set out a blueprint which included measures to ensure state based electricity businesses made use of competitive forces to bring about lower costs but also argued that private ownership was necessary to ensure gains are quickly taken up and become on-going. The Commission was forthright in articulating its view that "Ownership clearly does matter." (Vol 2 p. 154). Privatisation was recognised as being important in bringing disciplines of capital markets and "the sanctions provided by the possibility of take-over and the risks of insolvency. Privatisation was also seen as a means of significantly reducing the scope for interference by governments." (Vol 2 p.147).

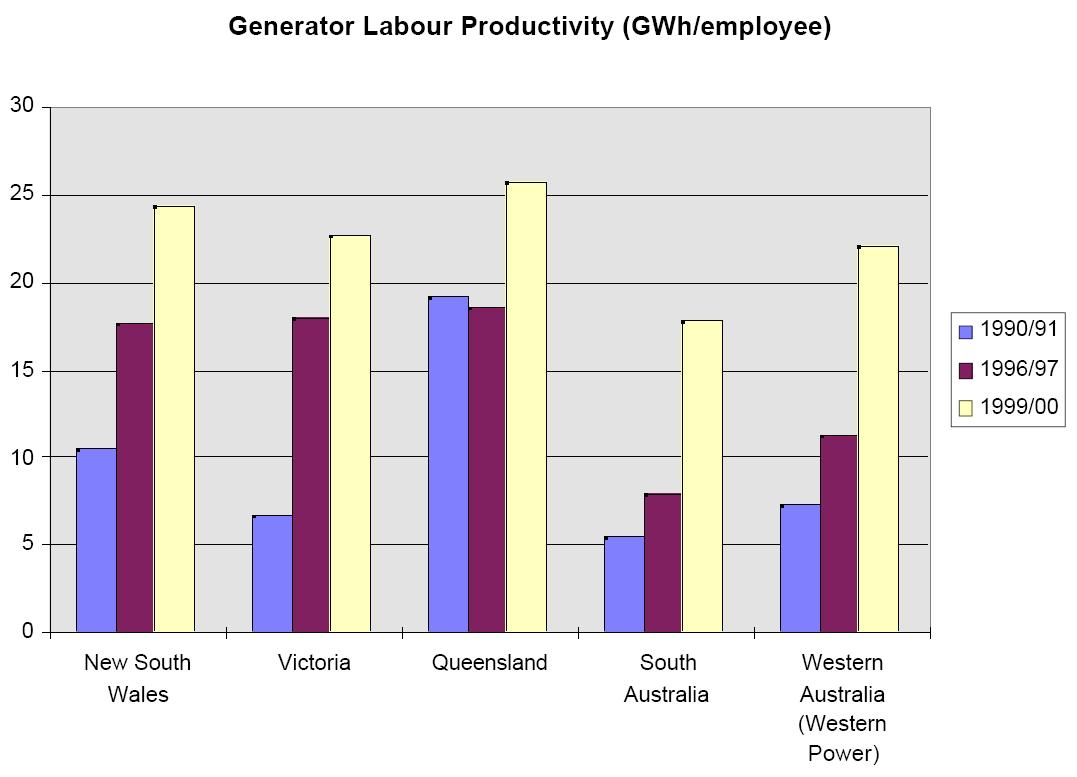

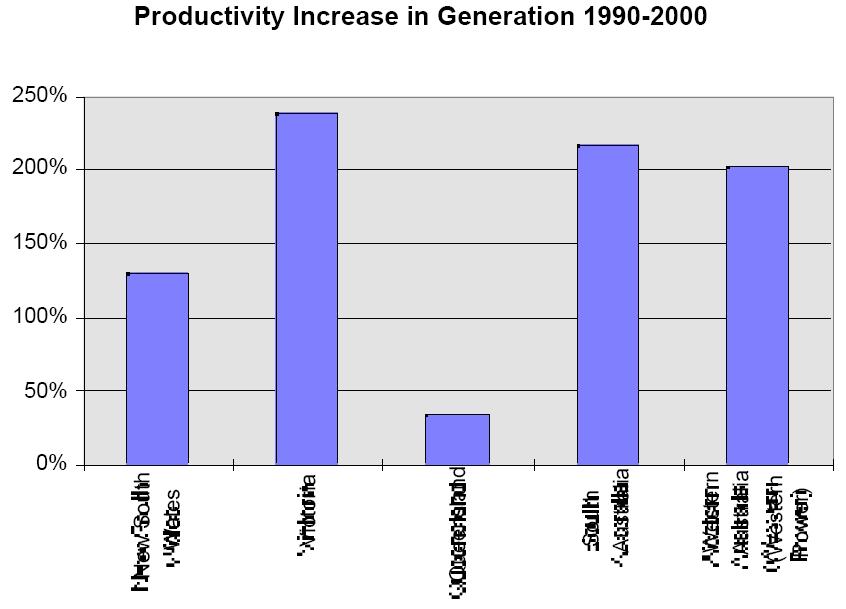

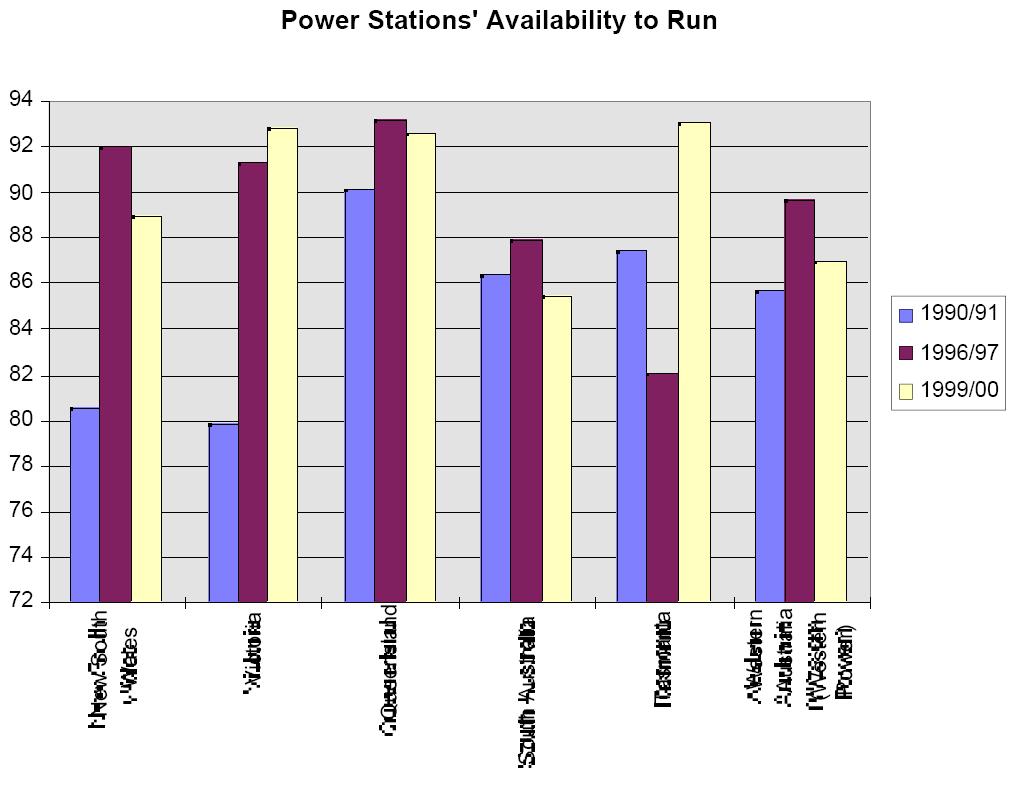

Gas production, transmission, distribution and retailing is now largely privately owned in Australia. (4) Electricity remains mixed and the NSW Opposition's policy announcement against privatisation in that State (5) is a setback for the reform process. Appendix 1 examines the outcomes of the privatised Victorian industry against that of other states. In general the data offers strong evidence to support the notion that privately owned businesses perform better than their government owned counterparts.

On-going government ownership of the energy industries continues to exercise a major suppressing effect on the industry's efficiency. It does so notwithstanding the undeniable improvements that have followed from governments implementing corporatisation of their own business entities.

Private ownership's advantages are often said, correctly, to be less important where there is natural monopoly. Natural monopoly occurs with large elements of transmission and distribution in both gas and electricity. But even here there are persuasive reasons to move down the private ownership path. These reasons include the fact that the natural monopoly might not prove enduring -- something now being seen in both gas and electricity transmission -- and because profit motivated cost reduction disciplines are so much more potent when under the control of private shareholders.

RECOMMENDATION 1

The Energy Market Review should recommend that governments develop privatisation programs for those energy businesses they continue to control.

2. DISTRIBUTION AND TRANSMISSION ISSUES

2.1 The regulatory approach

Among the four industry components, local distribution of electricity and gas is normally the most important component of price. It also presents the most enduring regulatory issues, since as we shall argue, transmission is fast emerging from being correctly seen as a natural monopoly, though it is yet to escape the regulatory prison.

2.2 Essential facilities regulation

With any market, there is no doubting the importance of a legal framework in allowing efficient commercial interactions. And although regulation is a short-sighted policy where markets are competitive, there is a strong case for the regulation of an essential facility

There is a key distinction between a facility that has been developed without any protection or support from government and one that has been developed under some sort of franchise (or, like much Australian infrastructure, by the government itself). Where the monopolist has seized his position by spotting an opportunity and offering value, the government regulation is pure coercion. Where the monopoly is created by law, the monopolist is clearly bound by the terms of the original grant which include the quid pro quo for that grant. Those undertaking a development of the former kind need not and should not face regulation regarding access or price.

Professor Richard Epstein (6), one of the world's leading authorities on constitutional and property law, however does not consider the distinction between a franchise protected "essential facility" and one that developed without any privileges as being as crucial as this. Much of his analysis (like the key English and American cases that established precedents) rests on the seventeenth century tract by Lord Matthew Hales de portabis mari ("concerning the gates of the sea"). In that tract, which was not published until the 1780s, Hales argued, that an asset (he was discussing cranes in ports) can be "affected with the public interest" either "because they are the only wharfs (sic) licensed by the queen" or "because there is no other wharf in that port".

Although not accepting a sharp dichotomy of approach between government supported and purely entrepreneurial infrastructure, Epstein argues "....regulation must be justified on the grounds that any monopolist charges too much and sells too little relative to the social -- that is the competitive -- optimum. But even when true, the case for regulation is hardly ironclad. The situational monopoly may confer only limited pricing power, and its durability could be cut short by new entry, or by technical innovation. Regulation could easily cost more than it is worth, especially if the regulation entrenches present forms of production against the innovation needed to undermine its economic dominance." (p. 284)

But Epstein's view is that an essential facility will inevitably be regulated -- something observable with railways in England from the mid nineteenth century. That being so, the issues remain to define the facility, at what point of time it is to be regulated, and how to ensure its owners have sufficient incentive to operate efficiently. Judging by outcomes the world over with rail regulation the task is extremely difficult. Appendix 2 offers further argument on these issues.

2.3 Regulatory decisions on price

In the final analysis, dominating the regulation debate is the prices that businesses are permitted to charge. In the February 2002 edition of the publication of the Utility Regulators' Forum, NETWORK, Professor Fels argued that in separate research Mr Rod Sims and NERA have both indicated that regulation is providing more than healthy returns compared with unregulated businesses. The work cited sought to demonstrate that regulatory outcomes in Australia were more favourable to the regulated businesses than those in the US and UK.

A paper prepared by NECG (7) carefully assesses the NERA analysis. NECG's rigorous examination of regulatory decisions in Australia, the UK and elsewhere found comparisons that assumed all the regulated entities were of a "plain vanilla" variety is highly misleading. With reference to the NERA analysis, they found that:

- the sectors analysed were atypical of the average levels of risk-free rates and equity risk premia, and when other regulated industries were included the averages were markedly higher;

- specific regulatory measures taken in the wake of the Maxwell scandal had artificially reduced the rates paid on UK government bonds, and the consequential risk free rate; and

- the regulatory models used in the US and UK give investors greater certainty than those in Australia and hence require lower returns.

A variation of this final point was alluded to in a McKinsey report, which argued:

Regulators enjoy considerable discretion in determining prices for a forthcoming control period, so the outcome of the review is not easy to predict. Uncertainty produces what the market perceives as regulatory risk. This market perception must explain at least some of the increased cost of equity under the UK system. The beta (a measure of risk) for UK utilities is around 0.9, whereas the corresponding figure for US utilities is around 0.5 when adjusted for similar levels of debt. Thus the real allowed return in the United Kingdom must typically be more than 1 percent higher than the return in the United States. The cost to the United Kingdom's economy is between $2 billion and $3 billion a year in higher utility charges. (8)

It is also noteworthy that the Productivity Commission, in its Position Paper rejected the ACCC views that current comparative rates of return, together with the evidence of new investment plans in some regulated sectors, can be taken as strong evidence that the access regime has been benign in relation to investment. (9)

Regulators' price decisions have required prices considerably below those sought by the regulated businesses. Real WACC levels have also tended to decline over time. The following chart summarises the more recent decisions.

Table 1

| ISSUE | Regulator | Applicant charge | Determined charge | Date |

AGL gas

contract

market | IPART | Annual revenue

reduction from

$140m to $128m | Annual revenue

reduction to $99m | May 1997 |

| Vic gas | ACCC/

ORG | 9.7-10.2 return real

post tax | 7.75% return post

tax | October 1998 |

Wagga gas

(GSN) | IPART | Original 11.1%

later offer 9.0% | 7.75% | March 1999 |

Telstra

Interconnect | ACCC | 4.7c/minute | 2.0c/min. with 1.6c

suggested Sept 1999 | June 1999 |

Adelaide

Airport | ACCC | 8.89% real pre-tax or

$3.66/passenger | 8.25% pre-tax or

$3.45/ passenger | June 1999 |

| Mildura gas | ORG | Tender at 9% real

pre-tax | 9% real pre-tax | June 1999 |

| Albury gas | IPART | 9.6% | 7.75% | July 1999 |

NSW vesting

contracts | ACCC | 43.64 cents | no more than 40

cents | September 1999 |

NSW

distribution

prices | IPART | | 16% real price

reduction 1999-2004

7.5% (7.75% AIE, AE)

15% O&M reductions

(10% AE, 5% AIE) | 2000

Final Determination |

AGL

Pipelines for

the Central

West Pipeline | ACCC | Real pre-tax

WACC of 10%

tariff increasing

after 2001 at

CPI+1.36% | Real pre-tax WACC at

7.5% meaning prices are

frozen in real terms

post 2001 | September 1999

Draft Decision |

AGL

Pipelines for

the Central

West Pipeline | ACCC | Real pre-tax

WACC of 9-9.5%

tariff increasing

after 2001 at

CPI+1.36% | Real pre-tax WACC at

7.8% (10.55% post-tax

nominal) tariffs as

proposed for 2 yrs then

to fall by real 0.06% p.a | July 2000

Final Decision |

Victorian

Electricity

Distributors | ESC | Pre-tax real WACC

AGL 8.6%

CitiPower 8,5%

Powercor 10.6%

TXU 10.5%

UE 9.7% | Pre-tax real WACC

7.1-7.4% draft

6.8-7.2% final

Year 0 price

reductions (%)

Original Final

AGL 17.1 15.5

CitiPower 12.4 11.2

Powercor 19.6 14.5

TXU 21.8 18.4

UE 12.9 9.1 | December 2001

Final Decision |

| Powerlink | ACCC | | Pre-tax real 7.04% | July 2001

Draft Decision |

The popularity of the recent film "A Beautiful Mind" has thrown into relief the importance of risk in decision taking and the application of game theory in reducing such risk, thereby offering mutual gains between parties as well as winner-takes-all zero sum gains. The application is especially relevant to situations where parties learn from each others' behaviour and modify their actions accordingly. While at first glance a regulator may take the view that disallowing certain costs as a part of the charge base brings gains to the consumer, second round outcomes are less certain.

The issues of comparative rates of return has featured in all seminars and conferences that examine the appropriate WACC or other measure of return. Commonly those seeking a lower return would point to BHP and cite that company's return on capital of, say 7%, and argue that the regulator has been over-generous to the regulated entities in offering a return higher than this.

What this neglects is the fact that BHP has a number of entities that earn a great deal more than 7% and is a business successfully striving to improve its returns by divesting the underperforming parts and seeking to expand the better performing parts. And the BHP activity closest to the regulated energy industries is Bass Strait gas where the business would earn a return on its investment of several hundred percent.

Moreover, the rate allowed in regulatory decisions is based on a risk-free situation. Projects have levels of risk that different proponents will disagree upon. Putting a maximum return at some average level computed from Stock Exchange data leaves little incentive to embark on riskier projects. At the same time, it destroys the symmetrical nature of the average spread of returns by cutting off the upside, thereby automatically reducing the true return the business can make.

2.4 The efficiency of regulatory law and its effects on property rights

2.4.1 Regulation and efficiency

Unless they perfectly mimic market forces, regulations of the uses to which property rights may be put reduce the value of private property rights. Such a reduction in the value of assets' output, as the Productivity Commission noted (10), tends to deter investment by raising hurdle rates. This means that assets generally and their associated labour and raw materials are used less than fully productively on an economy-wide basis.

This is just one of the deleterious effects likely to follow from intervention into the rights that private owners have in the use of their property. Also likely is a suboptimum level and pattern of operation and maintenance expenditures.

Any government action that might diminish the value of private property rights should, therefore, be introduced only after the government has assured itself of the existence of countervailing benefits.

Government intervention in the normal interactions between buyers and sellers and associated parties has the capability to undermine property rights and hence investment. In addition, it can bring costs that distort on-going operational actions.

2.4.2 Paperburden costs

Governments should ensure that firms are not diverted from seeking to profitably meet consumer needs. Regulatory certainty and stability are essential to allow this. Where businesses confront intensive regulatory oversight, the risk premia they require to embark on activities that involve sunk costs are increased. In addition they are constrained to set aside resources to counter adverse effects on them from the regulations. Both of these outcomes entail costs that have no corresponding benefits. Efficiency requires that governments minimise regulatory restraints on businesses whether they be privately owned firms or corporatised public firms designed to face similar disciplines and incentives.

Governments have created a plethora of regulatory agencies to control the energy industry. At the Commonwealth level, regulatory agencies fall under acronyms that include ACCC, NCC, NECA, AGO and NEMMCO. In addition, all states have their own regulatory agencies -- for Victoria alone, those overseeing the energy industry include Essential Services Commission (ESC), VENCorp, EIO and OCEI and OGS. These agencies risk shifting the entrepreneurial activities of the industry's firms from a customer-directed to a regulator-pleasing perspective.

And none of these agencies, which collectively require some $200 million a year of public funds, actually produce anything. Instead they provide directions, some of which are necessary, to the producers and sellers of electricity and gas on matters like:

- the prices they may charge,

- their permitted terms of dealing with each other,

- the fuel inputs they must use,

- the safety arrangements they must take, and

- the way they must treat their customers.

To do all this, the regulatory agencies have spawned a plethora of hearings, reports and decisions. For electricity, Victoria's Essential Services Commission (ESC) alone has produced or caused to be produced hundreds of documents, comprising well over a million pages.

Regulation also brings costs far in excess of the sums expended on the regulatory authorities themselves. As a rule of thumb, the paperburden of regulatory costs imposed on business is often quoted at twice the costs of administering the regulation by the government itself. (11) This rule of thumb would almost certainly understate the resources involved in the energy industries where the regulatory framework is central to the various businesses. Each of the hundreds of documents has some commercial impact -- actual or potential -- on a number of firms and requires consideration and responses.

The government/regulator is often increasingly driven to augment its demand for information once it commences along the path. This may be because of a different view between itself and the facility owner over what constitutes commercial behaviour. In most cases the demands for additional information would have required responses from all of the businesses even though they may be unnecessary or irrelevant for some.

Experience is demonstrating that the regulators' requirements on firms for the purpose of price setting are extraordinarily intensive. Firms often claim that the information demanded of them is not normally collected or not available in the way that is sought. These regulatory costs are especially high in the directly regulated "essential facility" businesses but also figure strongly in generation and retailing where government intrusion remains strong.

2.5 Outcomes of current access regulation

A number of submissions to the Productivity Commission's inquiry argued that regulators have adopted "pragmatic" rather than "efficient" pricing principles in practice, and that this necessarily reduces the likelihood that the theoretical benefits of price regulation will be attained.

However considerable uncertainty surrounds the question of whether, and to what extent, investments have been delayed, distorted or cancelled due to access regulation, with data being scarce and inadequate. Submissions have included those that attempted to provide broad measures and others offering more specific, or anecdotal, evidence. The submission of the ACCC is prominent in the former category. We have already noted the Productivity Commission's rejection of its claim that new investment plans vindicate the ACCC's views that the current access regime does not discourage investment.

In this context, evidence regarding the impacts of access regulation on specific investment proposals must clearly be given weight. The Productivity Commission's Position Paper cites a number of cases brought to its attention in the submissions, all but one of which suggest that access regulation has had disincentive effects. While the "sample" of project specific information is small in size, it is notable that a preponderance of the cases cited argued that access regulation was a disincentive to investment. Indeed, BHP was alone in arguing that an access regime had, in its case, facilitated a new infrastructure investment. (12)

One particular instance that has come to our notice concerns TXU Networks, which sought a variation of its access arrangement to allow the profitable reticulation of gas into Barwon Heads in Victoria. This expenditure was not originally forecast and hence required the ORG's authorisation. The company sought a return on capital expenditure comparable to its internal hurdle rate for capital expenditure. The variation was rejected by the ORG and TXU deferred the investment to supply gas to the area. All parties were therefore losers: consumers were denied early access to a new energy alternative; the company was denied an ability to supply a profitable opportunity it had discovered.

Also of note in this context is the Melbourne Airport case, in which the ACCC sought to intervene in a case in which a voluntary agreement had already been reached between the facility owner and the access seeker. In this case Melbourne Airport and Impulse Airlines had agreed on terms for access by the latter to the new Domestic Express Terminal. In its submission to the Commission, Australia Pacific Airports Corporation (APAC) argued that:

"Ideally, users and providers should be able to agree on terms and conditions of supply free from intervention by the regulator. This not only ensures that operators are receiving an adequate return, but it properly reflects on the value that users place on services provided." (13)

The APAC submission argues that, by contrast, when regulators consider pricing mechanisms "the sole focus of attention is the provider of the service". As a result:

"...the apparent willingness to pay of a customer was not even mentioned in the ACCC's draft decision."

Moreover, it is argued that, despite the voluntary arrangement between the parties ultimately surviving the regulatory intervention by ACCC, there has been a tangible result in terms of investment disincentives. According to APAC:

"...as a result of the ACCC's conduct, the Board of APAC will now no longer approve investment in new aeronautical facilities until such time as a final pricing decision is available."

It is vital not to dampen the profit motivated efficiency drives including seeking out new opportunities that stems from private property rights and outcomes in terms of business decisions.

2.6. Benefits of adopting a more narrowly focused regime of access regulation

Much of the regulatory literature over recent decades has, inspired by the work of Stigler (14), featured the notion of regulatory capture by the regulated entities. Yet, in more recent years at least, the risk has been in the opposite direction with the regulatory authorities engaging in what Shuttleworth (15) has called "regulatory opportunism" to reduce prices.

Regulatory opportunism tends to bring a bias in favour of insufficient rather than excessive supplier returns because the most important constituency for the regulator is the government and public opinion. Generally, a regulator's decision will be more welcome to consumers the lower the price levels they bring. Although setting a price that is too low will rebound on the system's development and eventually on the existing network's reliability, a self-interested regulator's time horizon will place a lower priority on the longer term. By contrast, a business accountable to private shareholders has a combination of capital maintenance and current income as the focus of its self-interest.

The Chairman of the Productivity Commission, Gary Banks (16), has also given recognition of this phenomenon. He says

As is well known, the traditional concern based on the American experience was of capture of regulatory agencies by industry incumbents, who have more incentive than anyone else to find ways of influencing how regulators interpret the rules in their particular cases. But, depending on the institutional settings, quite different forms of influence can operate. These include favouring the interests of current consumers (and electoral constituents) over the interests of future consumers; which could lead to new entrants being favoured over incumbents.

The question of the impact of access regulation on investment has been widely discussed. This discussion has included both theoretical considerations and attempts to analyze the impacts of the specific forms of access regulation currently implemented in Australia.

The potential for access regulation to have a "chilling" effect on investment almost certainly represents the major cost likely to be associated with it. It is, by definition, not possible to observe investment that has not been undertaken as a result of regulatory disincentives. However, the potential for regulation to lead to major dynamic inefficiencies due to distortions of investment behaviour is apparent. Anything that reduces an investor's returns is some disincentive to invest.

Disincentives to investment arise from specific concerns as to the risks to returns from particular assets due to the operation of a given access regime. They also stem from a general tendency to increased "sovereign risk" where governments are seen as overly willing to constrain private property rights.

A risk averse view is clearly required in such circumstances. This is likely to be more damaging to general welfare where the importance of dynamic efficiency outweighs that of static efficiency. In such circumstances the impact of access regulation is likely to bring income transfers, rather than income increases.

It follows that unless the investment need is stable, and we can be highly confident that the regulation will be benign, it is preferable to err on the side of failing to declare essential facilities, rather than on the side of declaring non-essential facilities. This preference is heightened because other remedies, both in competition legislation and in other avenues, are available to address errors of omission. By contrast, there are no immediate remedies identifiable to address errors caused by regulating unnecessarily.

Though all excesses of regulation will rebound on economic activity, they assume greater immediate importance where the access regulations have the effect of reducing expected values below those necessary to justify the investment. Commonly regulators may try to excise the "economic rent" type of excess profits. But doing so may reduce the potential upside gain which the project, to be viable, needs in order to counterbalance downside risk. This is a matter that looms especially large in cases when new (rather than expanded) investment is under consideration and where demand is uncertain.

This argument for avoiding regulation has greater force, particularly in relation to the issue of the extensive information required to underpin effective and efficient price regulation.

2.7 Addressing costs in regulated businesses

The previous section argued for a narrowing in the scope of access regulation. It is also essential that the form of access regulation should also be improved. The key purpose of reform in this regard is to reduce the extent of the negative impacts of access regulation on incentives and on perceptions of regulatory risk.

Two matters of particular importance are discussed in the literature in respect of the best way to value regulated assets. The first is whether to use forward or backward looking costs. That is, whether to take previous investment costs as the basis for determining current prices or whether to take the future costs of the equivalent investment as the basis of current costs. The difference is important because the future costs are often lower because of improvements in technology.

The second is whether to optimise investment by disallowing costs for investment that is unnecessary in the future. Again, disallowing unnecessary costs brings lower present prices for consumers.

As with many other outcomes of regulatory approaches, the appropriate course is contrary to that initially presumed to be in the consumer interest.

While for facilities that are competitive, it is not possible for the supplier to charge for assets that are shown to be unnecessary, the regulated facilities are by definition not open to competition. If such a firm were to be denied a component of prices that comprised costs that are either unnecessary or will be cheaper in future, an element of risk is added. The firms themselves will require a higher investment premium for future expenditures or will delay undertaking such expenditures until they are urgent.

Similarly, a forward looking regime may unduly discourage new investment where costs are falling in real terms. This effect can be at odds with the social optimum where demand is rising and some portion of the investment is underutilised in the initial years.

Of course, there is a contrary viewpoint. The regulator in attempting to mimic the market does not want to reward poor decision making or premature investment. And the regulator wants to avoid being in the position of forcing users to pay for "stranded" costs that are not efficient. The dilemma will probably always be with us and is the main reason why "light handed" regulation which is not related to actual input costs (e.g. CPI-X as in its originally envisaged UK form) should always be the preferred model.

2.8 Consistency between access regimes

The form of access regulation -- where such regulation is applicable -- should be made consistent, as far as possible, across all sectors. Thus, Part IIIA should form the basis for all access regulation, with industry specific access regimes being approved only where there are substantial industry-specific issues to be addressed. All industry-specific regimes should be made fully consistent with the general principles embodied in Part IIIA.

In particular, industry specific access regulation should not substitute lower "thresholds" for applicability than those applied in Part IIIA. In this context, we note as an example the submission to the Productivity Commission's inquiry of Australia Pacific Airports Corporation. This argues that, by declaring certain facilities to be subject to Part IIIA, the Airports Act has the effect of lowering the threshold for its application, in particular in terms of the "national significance" aspect of the criteria for application.

The mechanism of "declaring" that an access regime applies to particular facilities clearly precludes the operation of the generic processes by which the NCC informs itself of the views of the parties and reaches a considered view as to whether the criteria for application have been met. In so doing, it inevitably undermines the original Hilmer notion that access regulation is an unusual intrusion on property rights, which is to be used sparingly.

Finally, each industry-specific access regime should be subject to regular review to ensure its continuing need and that its form remains appropriate to the industry and the markets it faces. This view is consistent with the general view that regular regulatory review is essential to ensure the maintenance of regulatory best practices in a dynamic sense. More specifically, however, it is clear that many of the industries that are subject to access regulation will be characterised by rapid structural and technological change in the medium term. This suggests both that the need for access regulation per se may change over time and that the requirements of industry specific access regimes may also be subject to major change.

The frequency of such reviews may vary between different industry access regimes, reflecting different expectations about the rate of change. This has tended to increase. Existing "sunsetting" and mandated review requirements for legislation in Australia tend to work on five to ten yearly cycles which suggests that a five yearly review period should form the starting point for consideration in relation to individual industry access regimes.

As important as the frequency of such reviews is the nature of the review process itself. A fundamental consideration is that reviews must be conducted independently of the industry access regulator. They should be conducted transparently, by a body with adequate expertise, such as the Productivity Commission.

RECOMMENDATION 2

- The on-going requirement for every facility's access regime should be reviewed on an regular basis against the need, due to potential anti-competitive outcomes in the absence of such a regime, and costeffectiveness.

- These reviews should be conducted by an independent, well-informed non-regulatory agency like the Productivity Commission.

2.9. Inclusion of pricing principles

2.9.1 Some issues with current approaches

Pricing principles, where specified in existing access regulation, are often poorly chosen, being based on pragmatic, rather than efficiency considerations. In this respect the Freight Australia submission to the Review of the National Access Regime argues:

"Regulators should be mindful of the limitations and potential adverse effects that flow from a pragmatic, but poor, choice of pricing principles. Pricing principles that dampen investor incentives or undermine investor confidence would detract from the efficiency objective of access regulation". (17)

The submission to the Review of the National Access Regime of Energex similarly argued regulators have tended to follow poor pricing rules and that, for this reason, an approach based on the use of Section 46 of the Trade Practices Act may often yield superior results.

The choice of "pragmatic" pricing principles in practice is likely, in most cases, to be the result of recognition of the difficulty of obtaining the information required to implement "efficient" price regulation. To the extent that this is true, the adoption of a "risk averse" approach, involving erring toward leaving monopoly rents uncaptured, is a necessary outcome. Gans and King argue that:

"...the regulator will have to consider itself as leaving some monopoly rents with regulated service providers. In this regard, the rents are simply an incentive bonus...and not monopoly profits per se." (18)

Given the degree of imprecision involved, due to informational requirements, and the relatively "light handed" approach that recommends itself as a result, it is not clear that price regulation under an access regime would exhibit superior performance in practice to one based on prices surveillance legislation. It is doubtful that there is any justification for extending the application of access regulation based on its superior performance in relation to monopoly pricing per se. This, in turn, tends to support the adoption of a narrow view of the applicability of access regulation.

2.9.2 Some appropriate principles to use

As noted above, we believe that there is, in general, considerable scope for pricing principles to be undermined in practice by the regulator, via the exercise of his necessary discretion. Consequently, pricing principles must be detailed and carefully specified if they are to be able to improve regulatory outcomes and enhance accountability on the part of the regulator, by providing an improved basis for the challenge of decisions by the regulated.

Therefore, we welcome the proposal made in the Productivity Commission's Position Paper that pricing principles should be inserted into Part IIIA. We believe that the specific pricing principles proposed by the Commission in Proposal 8.1 are a useful starting point These are:

"The pricing principles in Part IIIA should specify that access prices should:- generate revenue across a facility's regulated services as a whole that is at least sufficient to meet the efficient long-run costs of providing access to these services, including a return on investment commensurate with the risks involved;

- not be so far above costs as to detract significantly from efficient use of services and investment in related markets;

- encourage multi-part tariffs and allow price discrimination when it aids efficiency; and

- not allow a vertically integrated access provider to set terms and conditions that discriminate in favour of its downstream operations, unless the cost of providing access to other operators is higher.

To these we would add provisions to meet two fundamental issues of price regulation. The first is the need for the evolution of such regulation over time to be consistent with the provision of incentives for continuously seeking improved productivity and efficiency performance. In order to deal appropriately with this issue, the following considerations must also be embodied in pricing principles:

- Pricing regulation should be "light handed" in its approach, both in terms of the extent of its attempts to capture monopoly profits and the information requirements imposed on the regulated;

- In pursuit of the above, it must be accepted that there should be some sharing of productivity gains between producers and consumers; (19)

- There should be recognition that, in a competitive market characterised by high entry costs and high levels of specific expertise, "super-normal" profits can persist for some time and are likely to be necessary to provide adequate signals for the entry of new competitors;

- Use of CPI-X regulation, to be fully incentive compatible, should incorporate price resets calculated on the basis of price monitoring with the X factor reflecting industry TFP, rather than rates of return or cost-based building blocks.

In the above context, that the need for price regulation to be incentive compatible over time is acknowledged in the Productivity Commission's Proposal 8.2.

A second issue that requires reflection in pricing principles is the need for an approach that is "conservative", in the sense of erring towards allowing facility owners to retain monopoly profits, rather than toward risking "under-compensation". The point to be underlined is that a conservative approach is required, not only to ensure investment incentives are maintained, in the positive sense, but to ensure "in the negative" that facility owners do not receive sub-normal, or even negative, returns as a result of failed attempts at a too "surgical" approach to price regulation.

Added weight is lent to this point due to price regulation being information intensive and, as a result, subject to a relatively high degree of error.

2.9.3 Building on existing experiences

Recent price re-sets for distribution and transmission have proven to be both acrimonious and resource intensive. The re-sets in Victoria and NSW have squeezed out any surplus profits (more than squeezed them out if transaction prices for Powercor and the share price for United Energy are guides).

Access to the distribution or transmission facility per se is not an issue -- only one of the Victorian distributors (CitiPower, which is in the process of being sold) is not separated structurally from its retail arm. Powercor/Origin and United/Pulse have different ownership structures for the two activities. Across Australia, transmission is carried out in totally independent businesses. The concerns about transmission or distribution businesses favouring affiliates has proven to be unfounded and there are ample means of addressing such concerns should they emerge.

Commenting on the deficiencies that the present "building block" approach to price setting, the Productivity Commission argued, (20)

"The approach is clearly highly information intensive and intrusive, which participants claimed reduces incentives for good performance. Specifically, it requires the regulator to:- seek extensive information about a facility's existing and forecast costs, including of any services not regulated (to prevent cost shifting);

- form judgements about whether costs such as operations and maintenance are based on efficient service delivery; and

- seek information about planned capital expenditure and form judgements about whether that expenditure is justified. This is because capital expenditure will increase the asset base and, therefore, the allowed dollar rate of return.

"The need to forecast future costs, and to validate proposed capital expenditure, could lead to the regulator having a significant influence over the running of the business."

These developments mean it is now timely to reduce the level of regulatory intrusion. The originally conceived notion of CPI-X regulation has been gradually modified into a form of cost based price setting. Recognising the appropriateness of the level of prices based on those presently in operation, an X-factor based on Total Factor Productivity should now be set in place. There is ready information on levels of Total Factor Productivity trends that can be used to set such levels of aggregate price. Within the average price level, businesses should be free to make variations to cater for different demands.

RECOMMENDATION 3

Implement future price settings based on CPI plus an externally developed Xfactor that incorporates Total Factor Productivity, with

- full flexibility within the overall price setting for shifts that reflect cost changes; and

- to ensure investor confidence, place major restraints on future regulatory actions that might modify the basic CPI-X outcome.

2.10. Provision for "access holidays"

Access regulation can have significant disincentive effects on new investments in infrastructure through its impact in reducing ex ante expected rates of return. This effect is clearly most pronounced where the construction of new facilities is being considered, as the degree of uncertainty as to the returns to the project will generally be greatest in these cases.

Following from the earlier discussion of property rights, we maintain that access regulation and price controls should not apply to infrastructure that is developed without the benefit of a government franchise, or other government support. In the current Australian environment, the adoption of this approach would be likely, in effect, to exempt most new infrastructure investment from coverage by access regulation. (21)

In the absence of a narrowing of access coverage, a "second best" amendment would be that access regulation be reformed to provide explicitly for the use of "access holidays" in relation to new infrastructure projects. Those projects were certainly not "essential" when conceived because life went on without them. But following earlier analysis, it can be persuasively argued that they progressively migrate into the "essential facility" category.

Equating an access holiday to a patent is a useful view of the concept. It suggests that the access holiday constitutes an explicit recognition of the right of the facility provider to the return on his investment as the quid pro quo for his creation of new value. It could also be married with the traditional common law concept of bottleneck facilities being "affected by the public interest", whether or not they were developed under a franchise.

The important point is that the access holiday should not represent a "concession" by the regulator. Rather, as it applies to facilities developed with no or minimal government assistance, it is a recognition of the facility-owner's property rights.

Consistent with this reasoning, implementing access holidays using "null undertakings" may be inapprpriate. The undertaking mechanism functions as one in which facility owners "voluntarily" cede access to their property on certain terms, under threat that arbitration by the regulator may yield less advantageous terms. It was not envisaged as a means by which property rights may be positively affirmed. Moreover, use of the undertaking mechanism may create a presumption -- or some pressure, at least -- toward the specification of "post holiday" access terms as part of the "null undertaking". This would be misconceived because there is a the need for consideration of such matters to be made at a later date in the light of the history of the facility and the returns made on it.

There is also some doubt as to whether Part IIIA, as currently drafted, allows for the use of "null undertakings". Amendments that would make explicit provision for access holidays would clearly be needed. In this context, it seems preferable to establish such provision separately from the existing undertakings provisions, given the different fundamental purposes served. Alternatively, it is arguable that provision of an access holiday is more closely equivalent to a "negative declaration", with the distinction (vis-à-vis existing declaration arrangements) that it would occur ex ante.

More important than the specific mechanism by which access holidays would be conferred is the question of the terms of the access holiday. The broad terms of access holidays must be explicitly set out in legislation if the desired effect, of minimising regulatory uncertainty and disincentives, is to be attained. This does not, however, prevent the inclusion of some element of flexibility to deal with different circumstances. These may include:

- Provision for variation of the standard period of the access holiday should be symmetrical: that is, it should also be open to the investor to propose that a longer than standard period is required due to the specific characteristics of the project;

- Any ability for the regulator to reject the holiday on the basis of the likely ex ante appearance of high profitability should be closely circumscribed, with a high standard of proof of both high profitability and relatively low risk (or uncertainty) being required; (22) and

- Additional flexibility should be provided by enabling extensions or augmentations of existing facilities (or network related investments) to be subject to access holidays, but that such requests would be assessed without any presumption in favour of acceptance.

Comments from the ACCC indicate that they, too consider that the concept of access holidays may have merit. (23) In this context, we support the ACCC view that

"The Commission does not want this process to be seen as one of picking winners. By this we mean that it is one thing to grant a regulatory holiday for all entrepreneurial pipelines, but it is quite another for governments to pick and choose which projects are granted this status".

However, we would question the ACCC's presentation of the question in terms of when market power would arise and be "able to be exercised", rather than in terms of the need to ensure that investment is not deterred by limitations on ex ante expected returns. The ACCC suggestion that there could be an ex post "deeming" that market power exists and the holiday is thus truncated would also have the potential to largely undermine the potential benefits of access holidays.

In sum, provision of access holidays would be a crucial "second best" mechanism for minimising investment disincentives, were the preferred option of exempting new investment that do not receive government assistance from coverage not to be accepted. Such holidays should be approved in a "quasi-automatic" fashion is fundamental to the achievement of the goal of access holidays. The use of a strong presumption in favour of a pre-set holiday period (say ten or perhaps twenty years) is equally important.

RECOMMENDATION 4

Access holidays or similar regulatory relief should be given to facilities deemed to be "essential" following a period of perhaps a decade of operation.

2.11 Competitive and entrepreneurial links

The notion of access holidays shades into the appropriate treatment for competitive links. In distribution, although there is one such link (in the Docklands area of Melbourne) it seems unlikely that these will proliferate, at least under current regulatory arrangements. For transmission, competitive provision is far more promising.

2.11.1 Gas

Already we are seeing competition in gas with the Duke pipeline to Sydney offering vigorous competition to the line from Moomba. Unfortunately, the competition authority, the National Competition Council (NCC) in this case, has impeded rather than encouraged the competitive process.

During 1997 Australian Governments introduced the national gas Code. The Code itself and its regulators pay lip service to the view that regulation is very much a second best approach to market competition. Even so, supposed market imperfections invariably offer the opportunity to regulate. Because of this, the Code has failed to herald a sought after new era of gas development. The regulatory arrangements have, in fact, stifled new developments, morphing the key skills of gas firms from commercial into political entrepreneurship. We are now seeing new pipelines being designed to avoid regulatory oversight even where this means higher costs.

One key criteria in the Code is that a pipeline should be regulated where this "would promote competition in at least one market". The regulatory authorities invariably render this down into the question of whether pipeline prices will be cheaper under a regulated regime rather than under one that relies on normal commercial interaction. Voluminous reports almost invariably produce the answer, "yes, a regulated price would be lower".

In the narrow context of a single pipeline, it would, in fact, be astonishing if a different answer were possible. Pipeline costs are 95 per cent sunk. Once pipelines are in the ground, price reductions will not force lower output, while the customers (and gas suppliers) can only gain by a lower haulage cost. And to justify cutting the price, the regulators can always claim the pipeliner spent too much in building the asset, underestimated gas demand, or that future costs will be lower. That way the regulators can claim they are not expropriating property rights.

But, when pipeline owners, observe such activity, they take steps to avoid repeat performances. For, although government bodies can force down prices of existing assets, they are unable to force investors to build new assets.

With pipelines, as with other assets, where governments assume control over property rights and force owners to sell at prices they think are too cheap, investment dries up. However, last year the Australian Competition Tribunal overturned the NCC's ambitions to regulate Duke Energy's pipeline from Bass Strait to Sydney on the grounds that competition was adequate. Indeed, a price war had already broken out between the two facilities.

Disappointingly, the NCC refused to relinquish such an important opportunity for regulation up an opportunity for regulation. It hired two American academics to write a report that said reciprocal treatment for the competing Moomba to Sydney pipeline (MSP) was not appropriate. The academics also showed touching faith in regulators' business skills. They maintained that because an ACCC draft decision proposed to reduce the price on the MSP further than it had fallen in the face of the competition from Duke, this proved the company was gouging the market!

In response to the regulatory decisions, we have two major prospective developments that are being tailored to ensure immunity from regulatory oversight. One of these, SEA Gas, links fields in offshore Victoria with Adelaide; the other, the Darwin to Moomba development would fulfil the Rex Connor's dream of bringing gas across the continent. The developers in both cases propose to size the pipes to cater only for pre-booked gas haulage, so that they escape regulation. This is in spite of the fact that pipeline economics mean costs per unit carried fall dramatically with size (for the Darwin to Moomba pipeline, capacity could be doubled at a cost increment of about 30 per cent).

2.11.2 Electricity

A recent report for NEMMCO by PriceWaterhouseCoopers and Clayton Utz (24) suggests that we should build more common carriage interconnects with regulated returns.

This is premised on transmission costs being only 5-10% of electricity costs. Hence, the authors argue, the benefits of greater competition and lower prices through generator competition are more than likely to outweigh any inefficiencies.

A major problem with this argument is it fails fully to recognise the scarcity of capital. Moreover, the sort of interconnects we are talking about are longer and more sparsely used than the existing main body of transmission -- Latrobe and Hunter Valleys to the respective metropolitan centres -- and the 5-10 per cent is not an accurate guide. SNI, linking SA to NSW for example, would cost $500 per kW in capital simply for transport, which is similar to the cost of an open cycle gas turbine or half the cost of a combined cycle gas turbine.

While conventional AC links are controlled by the laws of physics, DC links offer scope for a link to be controlled so that it is akin to a generator. Australia (through Transenergie) has been the pioneer in developing totally unregulated links dependent on arbitraged prices between regions for their revenue; some such lines are now under consideration in the US. (25)

This allows an entrepreneurial approach - competition in transmission, with charges paid by willing buyers. It was the lack of such a service that dictated a consensus in favour of regulated links. These, in traditional systems, involve several adverse effects:

- gold plating; A notorious issue with government developed facilities is the tendency towards over-engineering. The Victorian transmission system is a case in point. The general consensus is that a private organisation would have been more parsimonious. Government organisations are less disciplined than private organisations to these cost/benefit trade offs because the decision makers have little financial stake in the outcomes. While excessive capitalisation is one result of government ownership, an alternative outcome is a squeeze on new developments where a government general budgetary position is strained. The electricity industry throughout Australia has seen feasts, as governments have climbed on particular rationales for developments, followed by famines as a result of general budget constraints. Such famines are rarer with the private sector since the absence of investment capacity by one firm would not prevent a rival stepping in.

- we also have a political response; Government owned and regulated interconnects allow considerable scope for the pursuit of political goals using ostensibly commercial motives. This obscures the merits of a particular proposal. It leads to misallocation of production, often in the cause of regional development or saving of jobs of those whose votes are particularly valuable.

- finally, there is crowding out; A regulated monopoly transmission is financed by a compulsory charge on consumers. This differs from the alternative means of supplying the capacity: new generation, and entrepreneurial interconnect or demand saving measures. A compulsory charge is likely to crowd out those alternative measures, whether transmission or generation, and deny us the most economic industrial blend.

With competition now possible, it may be that the future will see no economic justification for anything other than a market provided entrepreneurial interconnected system, at least for major augmentations. At issue, on whether a line should be regulated or entrepreneurial, is whether it is:

- to allow improvements in reliability, spending that would be difficult to cover in fees, or

- for an augmentation.

Only in the former situation should regulated links be permitted. Welfare economics, on which planning rests, does not face the same incentives nor have the same quality of information on costs and risks that is found in the real market. A regulated link will crowd out entrepreneurial provision -- which could be transmission, generation or demand side measures.

Moreover, the apparent benefits added in the welfare economics case are invariably greater than those in the market case. This is because it is well nigh impossible to restrict all the benefits of a market development to those paying for it. For example, the welfare economics calculus estimates the value people place on a new development and adds in all the "consumer" and "producer" surpluses. Market outcomes are limited in this by all-comers paying the same price. Hence, much of the value of a welfare justified development should be discounted if its merits are to be compared to a market development. Otherwise it will divert capital to sub-optimal usages.

The Energy Market Review offers an opportunity to test these issues.

RECOMMENDATION 5

- In the case of gas transmission, access regulation should cease whenever there is competition, leaving any controls to general provisions of competition law which seek to combat collusion.

- For electricity, two opposing models are the UK national grid, which is a fully planned system; and the PJM system with comprehensive nodal pricing designed to ensure market responses to constraints.

The Review should consider what, if any, circumstances could justify approval for a regulated interconnector financed by a compulsory charge on customers (or suppliers).

2.12. Improving access regulation

In general, the scope of access regulation should be narrowed as far as possible, consistent with its underlying purposes. This is essential due to the general requirement in a liberal society for government to minimise its interference in private property rights and the more specific need to ensure that dynamic inefficiencies arising from the distortion of private investment incentives are minimised. In particular, it is argued that access regulation should be:

- Limited in its application to vertically integrated facilities;

- Limited to cases in which the provision of access is necessary to create the conditions for workable competition in downstream markets; (26)

- Limited to cases in which the duplication of facilities is clearly not economically feasible;

- Not applied to infrastructure developed without the benefit of a government franchise or any other support.

This opens the way to the development of the following more comprehensive set of policy approaches which amplify those offered in Recommendations 4 and 5.

RECOMMENDATION 6

To develop policy in recognition of the twin importance of property rights and competition, and the need to avoid intervening in voluntary arrangements between parties these principles can be placed into a taxonomic framework addressing six important classifications of essential service or bottleneck infrastructure. These are:

a) That which has been built without any market protection, especially that built since 1995 which is almost by definition "entrepreneurial" rather than regulated. In this case the preference should be "no regulation" since the entrepreneur had no privileges in seeking to find the customers and their needs.

b) That which introduces new competition, even if this is not identical to existing facilities. There is competition. No regulation should be put in place and regulation on the existing facility should be removed.

c) Privately built infrastructure built prior to 1995 that enjoyed no government protection. The onus here should be on the authorities to make a case for regulation

d) That which is owned by the private sector but was built under a regime that offered protection from competition. This presents a clear case for regulation but one that needs careful handling to avoid shutting out future competition.

e) That which was owned by a government but has since been sold under contractual terms to the private sector. These should be regulated according to the contracted terms.

f) That which was built by and remains owned by a government. This if it is not to be privatised needs to be regulated though in a way that does not pre-empt rival facilities.

This would place access regulation rules much closer to those envisaged by the Hilmer Report than is presently the case.

Should a facility developed purely as an entrepreneurial facility assume the nature of a monopoly "essential facility" this should be addressed by regulating following an regulatory or access holiday. As previously discussed, such a facility cannot be considered truly essential since life went on without it prior to an entrepreneur spotting a market need. Rolling such facilities into the regulatory net constitutes a deterrence to firms searching for the needs and undertaking the risky activity of meeting them.

2.13 Ensuring a consistent approach between new and existing transmission

2.13.1 Laying the groundwork for future augmentation of transmission

Efficiency is achieved in commercial operations where there is

- known, tradeable and fully defined property rights

- obligations and gains from these property rights are clearly established

- competitive supply and demand to prevent monopoly prices.

The existing electricity transmission network is operated on an open access basis. At present neither producers nor customers have any exclusive property right to the network. All costs other than those that are firm-specific, are recouped from customers. The transmission rights are non-existent, although ownership rest with the transmission business. There are no requirements on the transmission business to operate in a way that least inconveniences the buyers and sellers of electricity.

Ideally, costs should be paid and benefits accrue to the party most able to take action to reduce them or to augment them in ways that offer increased value.

If others pay, parties benefiting will use more of the services than they need. Thus, if generators are able to obtain access to markets with only the line losses counting as costs, they will avoid a great many of the costs associated with transport. The classic case is where gas is a fuel option; the gas generator must pay full haulage costs for the gas to the plant but will avoid the cost of hauling electricity from the generator to the market. The clear incentive is to locate the gas generator close to the gas source, irrespective of whether transporting the gas would overall be a lower cost solution.

In addition, the lack of exclusivity means a generator must rely on being lower cost than other possible suppliers along a given transmission path if it is to be assured of running.

Similarly, if customers are paying for the transmission on a regulated basis, they may not be assured of obtaining the cheapest source of power. The transmission business, as the owner of all the rights, has an incentive to economise on building new links as long as the market is fully supplied. It would have no incentive to build a new line from a cheaper source if this would leave an existing line partly "stranded".

In Victoria, these potential inefficiencies are countered by separating transmission planning from ownership. This is a sound approach but it would be even more preferable to have built-in incentives for the transmissions owner to operate with full efficiency.

Customer charges have a disincentive to efficient location similar to that of generators to the extent that the price they see is postage stamped over a large area. This means that a customer would see little value in locating close to power or in areas over-supplied with transmission.

2.13.2 The Nature of the Transmission Network

Conceptually, the transmission system may best be thought of as having two components: radial and meshed. The first delivers power from one or a number of generators to a major load node. The second delivers the power to the dispersed customers beyond the node. This shades into the distribution system.

Customers and generators alike have vital interests in both aspects, as does the carrier. However the interests are not identical along all parts of the network.

- Particular generators have a greater interest in the lines that connect their power to the node.

- Customers are most interested in ensuring that power is made available. Although they wish to see this coming from the lowest cost sources, they are indifferent as to which sources these may be.

The differentiation of the transmission network into the radial and meshed network indicates the necessity for different charging and property rights approaches. While customers in the meshed network must share usage of the network and agree or have imposed upon them a level of reliability and associated costs, generators have the overwhelming interests in particular radial lines.

2.13.3 Establishing rights

Some means of ensuring the transmission system is optimally operated is required. This is best accomplished by defining property rights so that the optimisation is the outcome of the various parties seeking to promote their own interests.

The difficulties in defining property rights include:

- the rights will always be shared in the great bulk of cases; hardly any lines connect just two related parties and the multiple users are likely to have different interests in upgrade, maintenance, timing of servicing;

- rights have already been allocated, often implicitly, especially in Victoria where there is private ownership of generation, transmission and distribution;

- definition of flow paths, loop flows etc.;

- definition of firm access and penalties for non-achievement;

- the expanded versus the sunk network and the difference between maintenance and new build;

- equity issues

- if existing businesses are freely given a right where that right was previously either not present or less firmly defined, they obtain a windfall gain to the disadvantage of currently non-existing businesses that need to pay for access

- giving a right to a business that previously had no such right (or an attenuated version of it) involves placing an imposition on another business.

These matters and others are to be considered under a review by NECA into transmission that is planned to commence shortly. Implicitly, generators have been afforded some notion of firm rights to the node. Under the vertically integrated systems that predated the national market, transmission and generation were built in lock-step. Indeed, there was over provision of transmission reflecting the low marginal costs of building incremental capacity along a particular radial.

Even though transmission capacity is variable, a concrete definition of "firm" capacity is definable and this should be done. As to the actual allocation and the payment, it is not possible to backtrack and re-allocate the implicit rights. They are in place and should be made explicit and tradeable. For radial lines to the various nodes, this capacity should be allocated at the level of capacity each generator held at the time of market commencement.

Any additional firm capacity should be offered through an auction system. And transmission operators/owners should have incentives to find ways of augmenting firm and non-firm capacity

This would still involve generation being scheduled on the basis of bid merit order but would require a generator without firm rights that constrained off a generator with such rights to provide compensation for that part of the latter's bid quantity that was offered below the pool price. A new or expanded generator would then have strong incentives to ensure adequate capacity augmentation or to buy rights from an incumbent.

This would then remove the incentive a generator has to free ride on existing facilities, where such facilities are scarce. It would sheet home the true costs of building capacity and delivering it to market, thereby leaving no bias against new building of transmission capacity.

RECOMMENDATION 7

To avoid having planning of transmission favouring existing owners, that transmission ownership and planning be structurally separated businesses.

RECOMMEDATION 8

That the present Review recommend to the planned review of transmission by NECA that a means of defining tradeable property rights to existing transmission be devised with this fully to take into account de facto rights.

3. REGULATION OF COMPETITIVE INDUSTRIES

3.1 Markets and Efficiency

As previously addressed, promotion of efficiency in markets is predicated on two features: strong property rights and vigorous competition.

Strong property rights are essential to ensure that sellers are able to keep the profits their activities generate. As a corollary, they must also face the likelihood of losses from taking the wrong decisions, losses that can lead to bankruptcy in extreme situations. This property rights perspective forces sellers at every stage of the market process to ensure that customers' needs are researched and met at the lowest cost.

Competition is essential as a discipline on this process. Without a competitor fully able and anxious to step in to supply the incumbent's market, the latter's motivation to continually search out new needs and cheaper ways of meeting them is blunted. Indeed, a seller with an entrenched monopoly will raise prices and reduce sales beyond the level at which additional revenue covers costs, secure in the knowledge that a rival would be unable to undercut the price. It is for this reason that a surrogate for competition is deemed necessary with distribution.

This process of competition is now generally accepted as offering the best means of setting the price and quality mix that gives consumers the best value. It operates in both the static sense of bringing about the lowest cost outcomes for a given set of demand and supply configurations and in the dynamic sense of encouraging a ceaseless search for improving upon this in the light of shifting demands and input costs.

All regulatory bodies claim that they are seeking to replicate this competitive outcome in the context of a market in which there are some natural monopoly elements that require synthetic costs to be developed. Hardly any authority would nowadays claim that regulatory overrides offer superior outcomes to those of a free and competitive market. Regulators simply do not have the capability to assemble and process the information that profit-driven suppliers routinely undertake.

Two areas of the electricity market generally considered to be amply constrained by competitive forces, at least in principal, are retailing and generation.

3.1 The Role of the Electricity Retailer

3.1.1 The retailer as the consumer's agent

Under competitive circumstances, the retailer is the de facto agent of the consumer. That role is assumed of necessity -- if abandoned or neglected a rival will step in. The retailer's activities, to ensure its on-going success and even its existence, must extend far beyond passively breaking down bulk and ensuring products are delivered at convenient locations. It must extend to assisting in discovering what the consumer wants. Unlike self selected (and often government financed) consumer "representational" bodies the retailer is compelled to be the agent of the consumer, as long as the consumer can move to an alternative agent if the retailer provides unsatisfactory service.

The retailer is an agent in a far more comprehensive sense than any representative body because it needs to weigh up the needs against the available product inputs -- and to do so correctly or face replacement. The retailer is under great pressure to seek out inputs from all sources.

The homogenous nature of electricity does not negate this. Electricity may be undifferentiable but its supply is from highly variable sources. In terms of assembling inputs, the retailer must decide, based on its customers' requirements (and those of its target customers):

- how much power to contract rather than buy at pool

- how much of different sorts of power (baseload, regular peak, needle peak) to buy

- how much price risk to take for the needle peak.

In addition, this basic product has to be metered correctly, bundled in profitable packages, promoted to consumers who may have little awareness of their needs and options, and priced appropriately. The retailer also needs to examine economies of scope (or synergies) in bundling his goods together with other similar products, sharing services of specialists like meter readers, back office functions etc..

Competition between retailers tends to ensure that, for a given quality, products are purchased from the cheapest producers and sold on to customers at margins that are not excessive in relation to efficient retailers' costs. Competition is also, and perhaps fundamentally, a discovery process, whereby the competitors set out to ascertain the needs of customers, where those needs are not well defined nor even fully understood by the customers themselves.

3.1.2 Regulatory impediments to retail competition in Australia