A Lecture to a Luncheon hosted by Quadrant,

Pavilion on the Park, 1 Art Gallery Road,

Sydney, 3 October 2003

I USED to be a member of Greenpeace, worried about the environment, thought everything was coming apart, when I read an interview with American economist Julian Simon, where he said, "listen, that's not true. It's not actually what the data shows."

My immediate reaction was that it was right-wing American propaganda, and I really was just pretty content to leave it at that, had he not said what I always tell students: go and check the data. It was only in the Autumn of 1997 that I started realising that a lot of the things he said were actually true. I thought it important to get that information out. I thought I should do so, so I published some articles in a Queensland paper. It blew up into probably the biggest debate we've ever had since the Second World War. That certainly indicates that this really is an incredibly important debate, and one that we really need to have.

A dossier that Greenpeace had compiled was, unfortunately, only one side of the argument, but it is what you'd expect from an interest group. And that tells us why this is an important discussion.

Let me just give you an overview of the two important points I'm trying to focus on. One is to remove the myths. To the extent that we believe that doomsday is nigh, I would like to try to show you some of the data and convince you that that is not true. The other is not to say that there are no problems, but to say, of all the remaining problems, which ones should we want to focus on? Because, really, there's only one bag of money, but there are lots of good things we'd like to do.

As long as we believe in the myth that things are going to hell, we're unlikely to make sound judgements. We really need to get the right data in order to make the best possible decisions.

So, are things really getting better? Yes, on many accounts. We have more leisure time, greater security, fewer accidents, more education, more amenities, higher incomes, fewer starving, more food, and a healthier and a longer life. This is not just true for the industrialised world, but also, perhaps more surprisingly, for the developing world.

Let me just show you one of those graphs that -- and you'll have to forgive me -- I think is sexy. The best information that we have about the world -- and also I should just mention, I'm not making up my own data -- come from the best sources in the world, typically the UN organisation. This is from the Food and Agricultural Organisation of the UN, from 2001 [Figure 1].

What we see here is the caloric availability for the developed and developing world from 1961 until 2000. If we look at the developed world, we have more than 3,000 calories per person per day. If we have any problem, it's probably being too fat. The main problem, of course, is in the developing world, where we actually have a dramatic increase in the availability of calories. From 1961, the average person in the developing world had 1,932 calories; on average just about what it takes to sustain life. Today, that number is up around 2,650 calories per person per day. It's a dramatic increase -- about 40 per cent -- and of course it's also testimony that people are actually living much better lives.

I want to point out two things though. I am only saying that things are getting better. It's not that things are fine and that there are no problems. To say, "things are getting better", is a scientific judgement, whereas to say "things are fine" is a political judgement. So, all I am saying is that, scientifically, things are going the right way; that this graph is actually moving up. I'm not saying that, hey, they have 2,650 calories, that's fine, they don't need any more. We can say that not only have things moved in the right direction, but that we can do even more.

The other point is to say that there are lies, damn lies and statistics. It is true that you can lie with statistics, but they are also the only source that we really have to understand how the world works. Figure 1 shows an average. It could be true, for instance, that the middle class in the developing world is eating up that extra stuff. But that's not actually true.

The UN has made estimates of the number of people starving in the developing world since 1970. In 1970, about 35 per cent of all people in the developing world were starving. Today, that number is down to 17 per cent. In 2030, the UN expects it to be down to 6 per cent [Figure 2]. The point again is to say that it's much, much better to live in a world where only 6 per cent of those in developing nations are starving, than one where 35 per cent are starving. But it doesn't mean that there's no problem.

In 2030, there will be 400 million people starving -- unnecessarily so. But it's not because we can't produce the food. It's because they don't have the money to buy it. So again we can say that things are moving in the right direction. We can still identify problems, and start thinking about what, in fact, the most important problems are.

With all these things getting better, however, is it true that all the environmental indicators are going in the right direction too? Well, generally, yes. Not all, but most of the important ones certainly are, and especially for the developed world where we are rich. We really have succeeded in creating a better world. But many people will argue that it is not sustainable. One of the main questions asked is, will there be enough of both natural and artificial resources? I showed you one thing with food. There will be more people, but at the same time we'll actually be able to feed them even better, by the best predictions that we have from the UN, till 2030. But what about resources?

This is one of the main fears that we all had back in the 1970s: the feeling that we would run out of everything. Let me just show you one graph which looks at oil [Figure 3]. An old Princeton Professor a couple of years ago said we've been running out of oil ever since I was a kid. And, yes, that's true, we've always worried about it. Nevertheless, if you take a look at 1920, we know how much oil the world used. We also know how much oil the world thought was left over. Divide those two numbers and you get how many years was left over at 1920 consumption. With these numbers we find that there were 10 years left over in 1920. So, not surprisingly the American Bureau of Mines came out and said, "in 10 years' time we'll run out of oil". Now, you may be forgiven for thinking that in 1930 we'd be down to zero, but in 1930 we'd used 10 years' worth of oil and yet at this new higher level of consumption in 1930 we still had about 10 years' worth of oil at the new higher level.

Now that might be a little surprising. Not so surprising was that the American Bureau of Mines came out and said that in 10 years' time the world would run out of oil. So you might be forgiven for thinking that at least in 1940 we should be down to zero. The surprising thing was that despite the fact that we had now used 20 years' worth of oil, we used more oil in 1940 than we did in 1930 or in 1920, there was still eight years' worth of oil at this new even higher level of consumption, and so on and so on.

The curious thing is, the more we used, and the more we use, the more that is left over. This is not the same thing as saying that the Earth is not round. Of course it's not. The point is that the myth-driven idea that there is only so much, and when we've used that up we're done for, is silly. It's a little bit like going home to your fridge and looking in there and saying, "whoa, I've only got food for three days", so you're going to die in four. Basically, what we've done is that we've been able to find more resources and utilise these resources more efficiently, and in the long term, of course, we'll also substitute.

When we look at oil, at the present moment we know that we have enough fossil fuels for about 50 years. But if we take all the shale oil that's commercially available within the next 25 years, we have another 100–150 years. If we take all the shale oil that exists, we have enough oil for the next 5,000 years. However, the real point, of course, is that long before that, we'll have switched to other resources, probably renewables or fusion or something we haven't even thought of. Sheikh Yamani, the guy who founded OPEC, loves to point out that the Oil Age is going to come to an end, but not for lack of oil. Just like the Stone Age came to an end, but not for lack of stone. It wasn't like, Oh, God, we've run out of flint, we've got to move to bronze, right? The idea was that we actually found better alternatives and this will happen with oil.

This principle also holds true for coal, non-fossil fuel and non-renewable resources, the most important ones being cement, aluminium, iron, copper and zinc. Of course, nobody every worries about running out of cement. But the other resources, despite the fact that we've increased our consumption globally over the last 50 years anywhere from 2 to 25 times, have all shown increasing user consumption, not decreasing user consumption. The economist would, of course, say that this is because the price has dropped on all basic materials over the last 150 years by about 80 per cent. It's become more abundant, not more scarce.

Clearly we have a myth that just doesn't stand up to scrutiny. We're actually leaving our kids and grand-kids with a greater availability of resources. We're using up the easily accessible iron ore, but at the same time we are leaving them with technology that enables them to dig deeper and use less good iron ore even more cheaply. So we really need to reassess our understanding of what the problem actually is. Again, my main point is to say that not only have things been getting better but they're likely to continue to get better into the future.

Air pollution is by far the most important environmental problem. The US Environmental Protection Agency estimates that anywhere from 86 to 96 per cent of all social benefits that stem from any kind of environmental regulation come from regulating just one pollutant, namely, particulate air pollution. However, most people in the developed world believe that air pollution is a fairly recent phenomenon that's getting worse and worse. But that's just simply not true.

Let me just show you the graph for London which is the one that we have for the longest period of time [Figure 4]. Here we have particulate air pollution, showing smoke from 1585, where it has increased up to about 1890, and from then on declined dramatically, so that today it's now down below what it was in 1585. We need to tell people it's not true when you think that air pollution is getting worse. For London it's improved over the last 110 years. Actually, London air has never been cleaner since medieval times.

Notice that this is not saying that we shouldn't do anything about it. We can also say we want to do even more. Because particulate air pollution is such an important issue, however, it makes sense to invest very heavily in more technology and get a worthwhile environmental benefit. We should invest in things that are smart.

You will notice that whilst decreasing air pollution is true for all developed countries it is not true if you live in Beijing or Bangkok. There, things are actually getting worse and worse [Figure 5]. But it's not very surprising either. That's exactly what we saw in London. Basically, if you don't have any industry, you don't have any pollution, but you don't have any money either. So you say, cool, when I get industrialised, I can start buying food for my kids, give them an education, maybe buy stuff for myself, and so never mind, I cough. That was the trade-off that Londoners and many of the rest of us made, and it's only once you get sufficiently rich, at around US$3,000 PPP [purchasing price parity] per person, you start saying, Ah, now it would actually be nice to cough a little less.

And so you buy some environment. Already, if you look at some of the richest developing countries such as Mexico and Chile, we've seen declining levels of air pollution both in Mexico City and Santiago, exactly for that reason. So the point is, not only have things been getting better, we're actually cleaning up. We're leaving a cleaner world for our kids and grandkids -- certainly in the developed world -- and it's likely to happen in the developing world once they get sufficiently rich too.

These are the important facts to get out to the public. But, of course, the question still remains: are we dealing sensibly with the problems that are still there?

I'll now just give you a very quick run-down on global warming. First of all, I'd like to say global warming is happening and it is important. The total cost of global warming is not, by any standards, trivial. It's going to be somewhere around five to eight trillion US dollars. Yet, I would still maintain that we need to question how important this is, and what we are going to do about it.

Furthermore, global warming is a limited problem, basically because eventually we'll move over to other fuels. We know that renewables have been coming down in price about 50 per cent per decade over the last 30 years, so it's very, very unlikely to expect that we are still going to use massive amounts of carbon fuels by the end of this century. This, of course, is important because you have all heard the predictions from the UN climate panel saying, it's going to be somewhere between 1.4 degrees and 5.8 degrees warmer, but only if we continue to use massive amounts of fossil fuels into the twenty-second century. It just simply won't happen. It is far more likely to have the median outcome of two to three degrees warming which is also the median outcome from the UN climate panel.

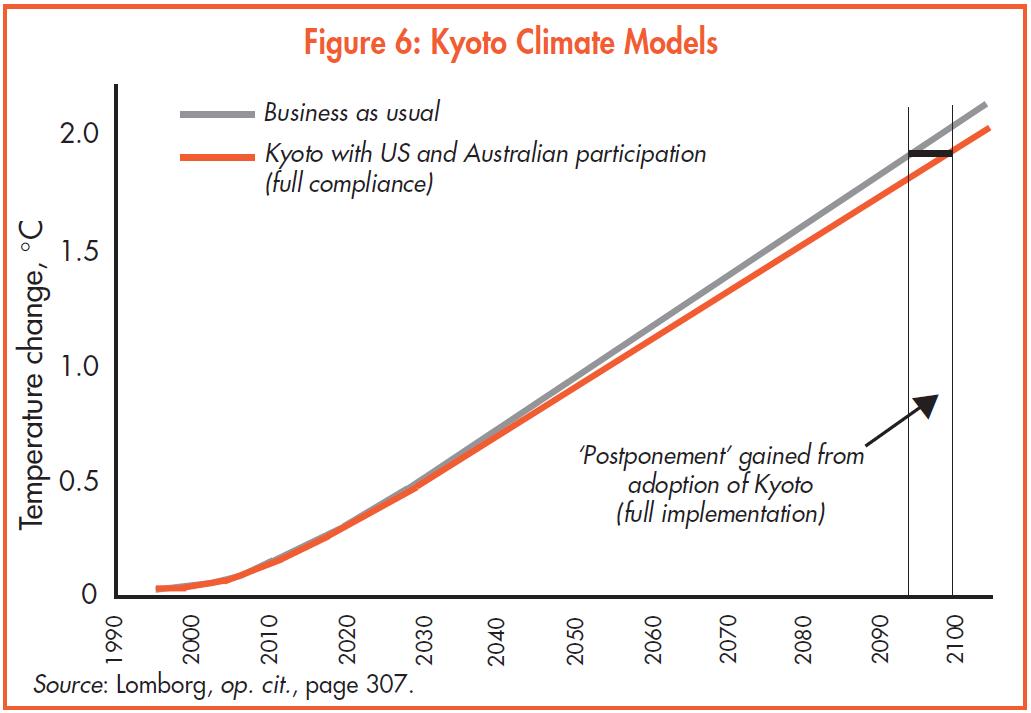

Well, I would actually argue that Kyoto will do very little good. Kyoto is just not going to do very much good at a very high price. Let me show you [Figure 6] the climate models from one of the lead authors of the 1996 UN climate panel report. All the models show essentially the same thing. If we don't do anything with global warming, this particular model predicts that over the next 110 years we'll get a temperature increase of about 2.1 degrees. But if we follow Kyoto and if the US and Australia were also in, and if everybody kept to their Kyoto requirements all the way till the end of the twenty-first century, then what would actually happen is that we'd get slightly less global warming. We'd end at 1.9 degrees, or, to put it more clearly, the temperature that we would have had in 2094, we would postpone until 2100.

So basically, doing Kyoto will mean that the guy in Bangladesh who has to move because his house gets flooded in 2100, can wait until 2106. I mean, it's a little good, but it's not very much good, right? On the other hand, the cost is pretty phenomenal. On all the major macro-economic models, it is estimated that we'll end up paying somewhere between $150 and $350 billion a year -- starting in 2010. That's not a trivial amount of money. To give you a sense of proportion, right now we spend about $50 billion globally on helping the Third World. So we're talking about spending three to seven times that amount to help the developing world very little in a hundred years from now. I'm simply asking, is that a good investment?

Actually, there are many other things that we could do that would do so much more good. Just for the cost of Kyoto in one year -- say for 2010 -- we could solve the single biggest problem in the world. We could give clean drinking water and sanitation to every single human being on earth. It would save two million lives each year. Perhaps more importantly, it would save half a billion people from getting seriously ill, every year. And that's just the cost of Kyoto in 2010. Then, in 2011, we could do something equally good. In 2012, we could solve the third biggest problem in the world, and so on.

Likewise, of course, we also need to make sure that in the long term we deal with global warming and we should invest in research and development of renewables that would cost a fraction of what Kyoto would do. If we could just bring forward the day we shift over to renewables -- by a couple of years around mid-century -- it would do much more good than Kyoto could ever do.

Why is it we don't hear this? Why is it that it's not an issue? I meet with a lot of politicians who say, yes, Kyoto's not going to do very much good, but that only shows we need to do much more. Usually it's not a good argument to say, yeah, the first step is a bad step, so let's take more steps in that direction. It might be, and we should certainly investigate that, but these models have already been looked at and they tell us that Kyoto's a bad deal and going even further is an even worse deal.

It is important to notice that a lot of environmental legislation does not have as a primary focus the saving of human lives. For instance, if we're talking about the Bengal tiger, it probably has the opposite effect. The main point is that when we're looking at policy whose main focus is to save human lives, we should go in and compare how efficiently the different policies do that.

The biggest study on this subject comes from the Harvard Centre for Risk Analysis, connected to Harvard University. The researchers spent three years going through all of the American legislation where there are published results on the cost and efficiency of saving human lives [Figure 7]. What we basically see is that the typical cost of saving one human life for one year in the health-related area is $19,000. In the residential area, it costs $36,000 and in transportation it's $56,000. In the work-related area, it's $350,000 to save one human life over one year, and for the environment, it's $4.2 million. We could also call this graph "Spot the Bad Investment".

Typically, we make very, very bad investments in the environment when our primary policy focus is to save human lives. We do so very, very inefficiently and we have to ask that crucial question: why is it we're willing to spend $4.2 million in saving one human life when we could have saved more than 200 elsewhere?

We've got to face up to the fact that our prioritisations are not free. This does not mean we shouldn't worry. This does not mean we shouldn't be concerned, but it means we should start being concerned about the right things. We must state what it is that's actually important, where it is that we should place our efforts, and make sure that we don't just do something that sounds good, that makes us feel good, but that actually has little effect in doing good in this world.