Address to the Monash Law School's Rethinking Regulation Forum

15 November 2006

MARKETS VERSUS REGULATION

REGULATION AND LAW

There are two means by which regulation is effected. One comprises laws that simply require things be done and the other is the expenditures of governments -- the taxes and subsidies that shift activities from where they would otherwise be. Subsidies are no less regulations than compulsive measures, since they rely on government for the funds they employ.

Both these forms of regulations differ from the fundamental role of laws which protect and define the property of individuals. Laws that protect and define individuals' property are at the heart of the reasons for government and derive their legitimacy from common law.

In addition to these regulations are other laws, which are more akin to conventions, like driving on the left hand side of the road or agreed units of measurement. These are best thought of as common sense measures that disadvantage nobody while facilitating interaction. They are not normally considered as coercive and therefore not included within the costs of regulation.

REGULATION AND MARKETS

There is no longer theoretical support for the political paradigm where markets and competition play anything other than the primary role. No respected authority nowadays maintains that state planning delivers more efficient outcomes than the interplay of producers and suppliers within competitive market conditions. Nor is there any practical example of a society that has achieved success whilst eschewing the market economy.

Competition allied with property rights is the source of economic efficiency. Competition forces suppliers to constantly look to market tastes and needs and to constantly review their costs out of fear that a newcomer will usurp their market position.

Regulation stops people spending their money, offering their services, building, playing and so on in the way they might otherwise choose. It therefore must be presumed to bring reduced welfare since it diverts activities from those that people would otherwise prefer. It means some individuals have to accept less favoured goods, services and activities than those they would have opted for thereby obtaining less pleasure per ounce of effort.

Regulation therefore confronts the Adam Smith benefit maximising process and as well presents a challenge to the liberty of the individual. A highly restrained role of government, the only means by which regulation can be enforced, is the defining condition of this.

Even so, the application of the free market approach is heavily qualified in practice.

Markets are popularly seen as being necessary to be overridden because of three sorts of reasons:

Monopoly which allows him to profit by restricting supply below the levels that would prevail under competitive conditions

Yet in fact, cases of monopoly where products are concerned e.g. IBM, Microsoft, Standard Oil, are never likely to prevail; the monopolist must always operate as though it is in a competitive market because a new technology or upstart is always waiting in the wings. More problematic is the case of the "natural monopoly" like power lines, or ports or roads.

Product or work complexities which are seen as too difficult for people to make rational decisions about; the trade-offs between risk and cost are seen as too complex and, moreover, the risk itself will mean some intolerable psychic and perhaps monetary costs imposed on the rest of the community if poor choices are made.

This has led to minimum safety standards on products, pre-reviews of safety by governments and workplace safety regulations

Externalities are the spillover costs that are imposed on third parties.

This has spawned the great array of environmental regulations.

TYPES OF REGULATION

It is useful to distinguish two types of regulation: economic and social.

- Economic regulation has previously received most attention because it most blatantly flouts the rules of sound economic policy. It is regulation of prices or access to markets, which is always likely to bring increased costs by distorting product offerings, denying the lowest cost competitors an ability to offer their services and reduce the competitive pressure on the existing suppliers.

- Social regulation is normally targeted at externalities; it requires suppliers to incorporate a more comprehensive set of features in their goods and services than they might have chosen to offer (e.g. impact resistant car panels) or it may require them to build to a higher specification (e.g. low energy using refrigerators) or it may forbid certain activities (like mining in natural parks, or logging or other activities where there are thought to be endangered species present) or it may require buyers to avoid the cheapest products especially with energy in pursuit of sustainable ecological development.

DEVELOPMENTS IN REGULATORY REVIEWS

LONGER TERM TRENDS

Regulation policy like many political processes moves in waves.

Nurturing the growth of modern living standards was regulation reform founded on a critical analysis and eradication of regulations, most notably in England from the Middle Ages onwards. The 200 years to the 1870's marked a systematic culling of laws and regulations. Of the 18,110 Acts passed since the Thirteenth Century, over four-fifths were repealed. The great majority of the repealed acts were constraints on competition. Naturally, with the observed economic success of England and its Colonies, other countries followed suit.

There followed a period, which lasted up to the last thirty years or so, when socialism and statism triumphed in public policy circles.

This led to market regulation, including its ultimate form nationalisation of many industries in countries other than the US. In Australia we had rail, buses, gas and electricity, telecommunications, shipping, insurance, banking, ports, gambling, brought under state ownership -- in some cases even excluding any rival private sector suppliers. Other countries saw the nationalised industries extended to steel, automobiles, coal mining.

Gradually though observed productivity levels demonstrated the greater efficiency of private ownership and of industries with competitive entry.

The push for deregulation was initiated in the US in the 1970s. Its greatest early focus was on the economic regulations rather than the social regulations that were even then increasing rapidly.

In Australia, the enthronement of deregulation remarkably came from a Labor Government, most of the members of which had railed against the inefficiencies and inequities of capitalism for a great deal of their public lives. Prime Minister Hawke, kicked the ball off in addressing the Business Council of Australia in September 1984 with a strong deregulatory message -- perhaps the clearest such signal previously given by an incumbent Government in Australia.

Chart 1: Pages of Legislation and Regulations Passed:

Commonwealth vs States, 1962-2004 Source: Annual publications of statutues and subordinate legislation. Pages of legislation and regulations for some years in some jurisdictions based on estimates. Does not include legislation or regulations from the Northern Territory or the Australian Capital Territory, and does not include regulations for South Australia or Western Australia.

Source: Annual publications of statutues and subordinate legislation. Pages of legislation and regulations for some years in some jurisdictions based on estimates. Does not include legislation or regulations from the Northern Territory or the Australian Capital Territory, and does not include regulations for South Australia or Western Australia.

Since then as the Banks Committee into Rethinking Regulation has observed there have been 20 reports on the issue, with less than spectacular outcomes. There are many ways of measuring this, all imperfect but it seems a development towards increased regulatory control is a rarely challenged finding. Chart 1 is the measure of annual new pages of legislation, very little of which is actually repealing extant regulation.

RECENT REGULATION REVIEW ARRANGEMENTS

Concern about regulatory excesses in the 1980s led to further reviews of "competition policy", particularly with the 1993 Hilmer Report. The report formed the basis for National Competition Policy, the key measures of which were:

- government owned businesses which compete with the private sector now enjoy no special advantages and suffer no disadvantages as a result of public ownership ("competitive neutrality")

- public monopolies were reformed, with their commercial and regulatory functions separated and their pricing policies subject to oversight

- all regulations which restrict competition were to be reviewed in order to determine whether regulation delivers a net benefit to the community.

Outcomes have been a substantial freeing up of regulatory restraints on competition in airlines, ports, electricity and gas, rail, and telecommunications. This has been accompanied by a deal of re-regulation in what has been over-ambitiously defined as the "essential service" components. But the net result has been positive.

National competition reforms extended the work of the Productivity Commission, which was largely directed at tariffs. Gradually governments have come to accept the benefits of lower levels of protection. Twenty five years ago, tariff protection in Australia was the highest in the OECD area today it has been reduced to the average 3 per cent or so seen in most other mature economies.

The ORR within the PC has been useful in highlighting problems with regulation. At the state level, Victoria has brought in some ostensibly strong regulatory oversight arrangements in the form of the Competition and Efficiency Commission. This has strong powers to assess new regulations and is being given commissions by the government to review wide areas of existing regulation. Although the new Commission failed its initial test -- the government allowed new regulations favouring renewable energy -- it may yet breathe more power into regulatory downsizing. The Victorian Government has set itself a target of reducing regulation by 15 per cent over three years and by 25 per cent over a longer period. It has also apparently committed to a one-in-one-out regulatory rule.

In this respect, with the reduction of economic regulation, State governments are more significant since their role tends to be greater in social regulations. NSW is about to implement some more rigour in regulation review following the report by IPART.

BENEFITS OF ECONOMIC DEREGULATION

Australia's deregulatory flourish, with all its shortcomings, has been accompanied by a vast increase in economic growth. From being one of the laggards in the Western world from 1972 to 1990, the Australian economy has been transformed to be the second highest growth rate of the mature economies.

In the case of the deregulated industries, massive gains have been seen.

For electricity and gas this is readily estimated. Electricity generation for example has seen labour productivity more than double. In some states the increase has been even greater five and three and a half fold respectively in the privatised Victorian and South Australian systems. (Chart 2)

Chart 2: Generator Labour Productivity: GWh / employee

At the same time, notwithstanding the fewer people they now employ, the power stations have improved their availability to generate, as can be seen in Chart 3.

Chart 3: Power stations availability to run

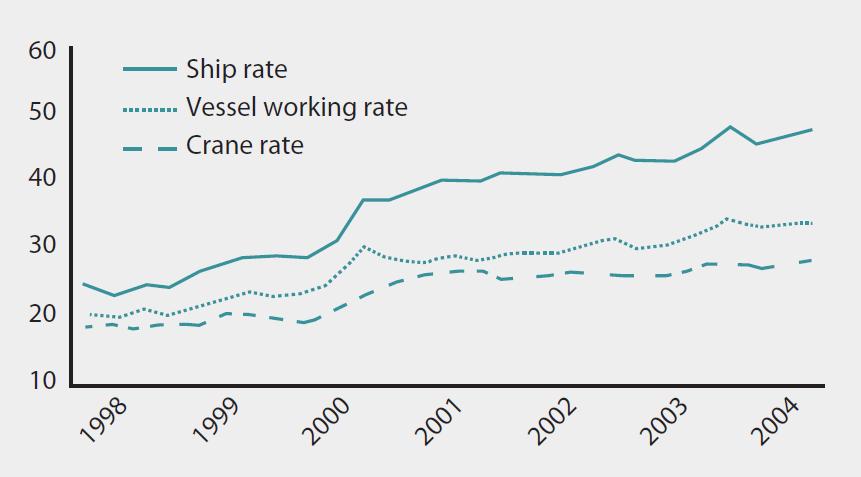

Chart 4: Container terminal productivity

Prices have remained low by world standards. On average in Australia prices to household consumers are only one third of those seen in the more expensive countries like Japan and Germany and are similar to those of Canada (US prices on average are about 30 per cent higher).

The sorts of productivity increases seen in electricity as a result of deregulation, including labour market reforms are seen in other industries. One notoriously inefficient Australian industry has historically been the wharves. Chocker block with Johnny Friendly union types and having the romantic image of the tough working guy, together with a great deal of monopoly power, reform of the ports was particularly difficult in Australia and was only achieved in the teeth of a bitter and lengthy strike during the course of which union power was smashed.

Port movement rates are well documented throughout the world in terms of TEUs based on 20 foot container equivalents. Notwithstanding considerable government blandishments and employment buy-outs, this level was under 20 per hour in 1992, whereas rates of 30 per hour were seen in the most efficient ports in our region. The TEU rate actually fell over the course of the next few years.

According to left wing think tanks, "(Federal Minister) Reith's dream of a 25 container per hour average across Australian ports is probably technically impossible." In fact the average rate exceeded 28 in the June quarter 2004.

The productivity rates are illustrated.

In terms of costs this has brought a real reduction of over 25 per cent.

NEW AREAS OF REGULATION

The deregulatory reforms have been confined to "economic" regulation.

What remains of this type of regulation is rump of price controls over "essential facilities" and the growing array of social regulations to protect the environment, workplace safety, and consumers.

ESSENTIAL FACILITIES

The most entrenched monopolies–perhaps the only ones with durability–are those supported by government. The central purpose of the Australian competition reforms was to smash these. In part, this meant hiving off the clearly contestable areas (e.g. generation of electricity). What is left is a set of residual apparent monopolies covering wires, pipes, ports and roads. Most of the recent policy debate has focused on the price and access conditions.

With perfect knowledge, the wise and incorruptible bureaucrat could devise a transmission system that would prevent monopolistic waste and could also bring about a great many of the dynamic gains achieved with commercial rivalry. However, these conditions are not present. Producers and carriers will be reluctant to reveal to competitors and customers alike the extent of their costs; and they too have imperfect knowledge of these. Buyers will seek to keep options open to the maximum degree, and will not reveal the full extent of their demand, their alternative means of having it supplied and their preferred means of supply.

Requiring private firms to provide access to competitors or others will diminish their incentive to build a facility or will distort the nature of that facility if built.

Control over essential facilities has brought considerably more regulatory intrusion than had been envisaged. At the time of the competition reforms the term "light handed" was in universal use. This has not been the outcome.

In electricity lines, telecoms and elsewhere, the regulatory authorities have been pre-occupied with preventing monopolistic gouging. This has led to extraordinary complex submissions being required, highly legalistic appeals of decisions and so on.

Although the ACCC argues to the contrary, the Productivity Commission found that the regulatory conditions were preventing investment in gas pipelines. Any new gas pipelines constructed under the present regime where open access is required and prices are determined by a regulator have incorporated costly inefficiencies to avoid regulatory control. The SEAGAS pipeline delivering Bass Strait gas to Adelaide for example is deliberately sized to avoid any spare capacity which non-participants in the ownership could use to recruit the ACCC to require access be given at a price not acceptable to the participants. This is a clear economic waste as designing in spare capacity can be achieved at a low cost.

Similar adverse outcomes can be seen as stemming from the regulatory control over the Dampier to Bunbury natural Gas Pipeline. The regulator's insistence of a price that the owner, Epic Energy, considered too low led to its bankruptcy. In addition, the low price made it uneconomic for Epic to expand capacity, an outcome of which was shortage of gas to allow increased electricity capacity with resulting black-outs.

Issues have arisen with other controls over essential facilities. One which became highly topical at the start of 2005 was Queensland's Dalrymple Bay Coal Terminal. This is regulated by the Queensland Competition Authority which set a charge of $1.53 per tonne in a draft decision compared to the current rate of $2.08 per tonne. The facility's owner, Prime, decided that it would be unprofitable to expand capacity with the result that the port is unable to cope with increased demand.

Similar restraints on the dominant telecommunications carrier, Telstra, threaten to constrain investment in that sector as well. Indeed, as a result of being unable to enjoy exclusive rights to new investments, Telstra has abandoned its fibre-to-the-node roll out. In addition, to avoid having its ADSL2+ assets declared an "essential service" Telstra is carefully ensuring its roll out only covers areas already serviced by competitors ADSL2+ networks.

Litigation under Part IIIA to force BHP and Rio to open their Pilbara rail lines to third parties is being pursued by the NCC. This is preventing the businesses from augmenting their systems to meet the expanding Chinese demand.

The Productivity Commission has been a useful counterweight to the ambitions of the regulators to maintain control. It recommended, against their advice, the deregulation of airports which the government accepted (the monopoly features of airports comprising landing charges account for only 10-15 per cent of their revenues and can be left to negotiation given the powerful players involved). Similarly, and in association with the analysis undertaken by the appeal body to the ACCC, the Trade Practices Tribunal, the regulatory controls on gas pipelines have been pinned back somewhat.

THE HOUSE BUILDING INDUSTRY

Land Availability

The open nature of the Australian housing market and its network of extensive sub-contractors has served the consumer well over the years and clearly contributed to low prices, especially compared with the heavily unionised commercial building sector.

But house/land prices have risen massively over the past year or so. Since 1973, houses have kept pace with inflation but land has outpaced average prices by four to eightfold.

The price of the land itself is a trivial component of the overall cost of housing -- less than $500 per block. To actually provide land for development with the roads, sewerage levelled blocks and so on costs between $35,000 and $60,000. Land for this purpose is almost infinitely available -- urban areas are only 0.3 per cent of Australia's land area.

A sufficient and flexible supply of land can alleviate demand pressures as evidenced by the experience of South East Queensland during the mid-1990s. A Rapid increase in the demand for housing due to inter-state migration was accompanied by a supply response possible due to the availability of land. The net result was a major jump in new housing activity with little pressure on prices either in the new or established housing markets, especially on the urban fringe.

Regulation therefore imposes an additional cost on housing of between $50,000 and $300,000 per block and represents a massive transfer of wealth from the have-nots to the haves, from those without homes to those with homes who are benefiting from the regulatory induced shortage and consequent price inflation.

Building Costs

Regulators are also doing their utmost to increase building costs in other ways. A favourite nowadays is a greenhouse inspired set of requirements for energy and water saving devices on new houses. NSW has an array of measures that must be incorporated into new houses and which involve the unfortunate new home buyer with unwanted costs. In Victoria, similar such measures were introduced with the Plumbing (Water and Energy Savings) Regulations 2004. Under these regulations, people buying new houses must install low pressure water valves. In addition, they have a choice of installing a 2000 litre rainwater tank or a solar heating system.

Often these regulations are introduced alongside phony Regulation Impact Statements (RIS). That in Victoria for the Five Star Energy regulations cited (but failed to quantify) savings from reduced greenhouse gas emissions. It made no attempt to quantify the reductions in consumer satisfaction that the RIS admits will result from the implementation of the proposals, or to acknowledge them via a sophisticated integration of quantitative and qualitative elements. In addition it relied on Keynesian multiplier effects (e.g. increases in employment, gross state product etc) to reach its conclusions, when these "benefits" are not accepted as a legitimate element of economic and/or cost/benefit analysis by a great many experts. The increased activity from regulatory forcings was considered as a benefit, whereas in fact such measures merely involve a transfer of expenditure into areas that would not be preferred absent the regulatory coercion.

The new home buyers' best regulatory choice, solar heating, involves an up-front outlay of $2000. This is for an unreliable energy supply that costs three times as much as conventionally generated electricity.

Hopefully, the Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission's inquiry into building rules will be the prelude to a much needed bonfire of these regulatory measures, and will flow on to other states.

There are other disturbing increases in regulation and evidence of regulatory barriers being erected to new competition.

In New South Wales, builders are now required to ensure that all power tools used on a building site are checked for safety by a qualified electrician every three months. It is hardly necessary to have expensive checks on 50 or more tools, some of which are used only once a year. It is even more doubtful that "tools" like portable radios and the kettle for morning tea should be as regularly and rigorously tested as heavy equipment. The home buyer pays for this nonsense.

Builders are supposed to meet every visiting contractor on site and discuss their work practices with them, no matter how experienced the tradesperson or how simple the job to be done. Builders and site managers are even expected to be responsible for ensuring their workers protect themselves against the sun.

Chart 5: New Land and House Package Costs

| 1973 | 1983 | 1993 | 2006 | Price Increase Multiple 1973 to 2006 |

| Sydney |

| Land | $9,100 | $29,400 | $107,100 | $460,600 | 49.6 |

| House | $18,900 | $43,200 | $121,500 | $128,250 | 5.8 |

| Melbourne |

| Land | $6,900 | $15,800 | $49,000 | $107,000 | 14.5 |

| House | $14,000 | $35,000 | $75,000 | $112,000 | 7.0 |

| Brisbane |

| Land | $7,000 | $27,000 | $60,000 | $135,000 | 18.3 |

| House | $16,000 | $37,000 | $70,000 | $112,000 | 6.0 |

| Perth |

| Land | $6,500 | $17,300 | $80,974 | $270,000 | 40.5 |

| House | $12,000 | $28,000 | $60,000 | $109,000 | 8.1 |

| Adelaide |

| Land | $2,000 | $12,000 | $35,000 | $140,000 | 69.0 |

| House | $12,000 | $20,000 | $40,000 | $90,000 | 6.5 |

| CPI | 20.5 | 61.6 | 108.9 | 150.6 | 6.3 |

Barriers to Entry

Other measures have been taken that will adversely impact on house prices. In the main these have been the result of regulatory "capture" and a symbiosis between regulators and the occupations they control.

In the past, the house builder was normally a tradesman who gained sufficiently wide experience to take on a management role in the project. The system of sub-contracting greatly facilitated this.

More recently there has been a rise in credentialism. Unlike in the past, builders now have to take written tests and demonstrate to the authorities a knowledge of the system that have not proved to be necessary in the past. One outcome has been an increase in people purporting to be "owner-builders" to escape the regulatory restraint.

This is turn has led to a vast expansion in the so-called owner builder applications which accounted for 37 per cent of building permit applications in Victoria last year. One facet of this has been the considerable limitations on the ability of an owner-builder to construct new houses and major extensions. As a result, provisions have been introduced in Queensland, NSW and recently in Victoria that are targeted against the owner-builder. In some cases they require the would-be owner-builder to attend a completely useless building course to force up the regulatory costs of opting for this method of building. These provisions have no effect in terms of the safety or functionality of the work (mandatory insurance is necessary in any case and there is no evidence that owner builder work is any less satisfactory than that built by registered builders). In fact, owner-builders are based on the same sub-contracting principles that prevail throughout the industry -- no owner builder actually lays the bricks or installs the roof trusses.

Regulation of Access to Buildings

An example of regulations that are motivated by the best of intentions concerns those under consideration to improve access into commercial buildings for people with handicaps. The proposals involve hundreds of additional requirements covering matters ranging from access ramps to hotel swimming pools passing space and installation of wheelchair friendly lifts.

The estimated building cost increases due to the implementation of the proposed standard of around $1.5 billion annually. The annual value of all new non-residential building approved is around $15 billion with a further $8 billion in alterations and extensions. It was estimated that the regulatory costs would add nearly 5 per cent to the cost of new buildings and over 10 per cent to the costs of upgrades for existing buildings which would need retro-fitment and see some loss of usable space.

In addition there would be costs stemming from the change in the nature of buildings constructed. For example, the cost impact is greatest on smaller offices and shops since the adaptations required of the regulations are more easily spread across larger building structures. This would mean a work and shopping environment less well suited to business and consumer needs. It is also likely to lead to premature scrapping of existing building which is more expensive to convert than building from scratch. And the higher costs that need to be passed on to customers would bring an overall reduction in building activity.

Nor is it clear that the outcome will bring an increase in employment of those with disabilities. Analyses undertaken of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which was passed in 1990 and is the blueprint for Australian proposals has seen a drop in the number of individuals with disabilities employed to 29 per cent in 1998 compared with 34 per cent in 1986.

Improving the access of disabled persons is a regulatory proposal with seemingly innocuous costs and targeted at relieving the discomfort and improving the work prospects of a highly meritorious group of people within society. Yet a careful analysis of the costs shows them to be far in excess of what most would regard as being reasonable, while an empirical analysis of the outcomes of similar regulation elsewhere indicates that the positive impacts envisaged are not easy to achieve.

AGRICULTURE AND FARM REGULATIONS

Regulatory framework for innovative food crop technology

The use of modern genetic technology to develop better crop varieties is recognised globally as a dynamic current area of technological innovation. The total land area sown to new genetically modified (GM) crops developed from biotechnology continues to expand globally.

Nevertheless, State Governments have banned the commercialisation of GM varieties that had previously passed stringent Federal government regulatory requirements to assure they pose no risks to the environment or to human health. The technology allows a marked reduction in the use of fertilizers and weed control chemicals as well as reduced labour use in the application of these chemicals.

These prohibitions and the long time lags in plant variety improvement mean that genetic technology used already for ten years by Australia's international trade competitors including in Canada and Argentina are denied Australian farmers. The competitiveness of the industries themselves and of those that use the products in food and other agricultural processing is impeded by the measures. In addition, Australian consumers will fail to gain the benefits of the lower prices that will emerge from the lower costs.

Moreover, as a result of this legislation and of the political risks posed towards plant biotechnology, some innovative plant breeding research groups have now been disbanded. This poses a longer term threat to the industry remaining ate the technological cutting edge where it needs to be to fulfil government and industry aspirations for agriculture and agricultural processing.

Regulatory "Takings" in water

Much of agriculture in Australia is generally on irrigation, especially in the Murray Darling Basin which contributes some 40 per cent to Australian.

Regulatory takings of water in pursuit of ill-founded but oft-repeated claims that water is needed to remedy environmental degradation are likely to have significantly impact economically on rural Australia while delivering little if any environmental benefit. Nonetheless, prompted by militant green NGOs, governments are attempting to take water allocations back from farmers.

Farmers need to have confidence about fair play with future decisions. Irrespective of the merits of the water allocation decisions and water rights acquisitions that have taken place over the past century or more, the status quo of de facto rights needs to be the starting point of any reformed system.

Native vegetation

Legislation on flora and fauna is similar in most Australian States, and prevents clearance of native vegetation. Specific issues are many.

Among these is an inconsistency in application. The reason is that regulations are devised at a high policy level and administered by local authorities, case by case, often by unqualified staff with no means of cross checking. Moreover, officials often have little experience in or knowledge of the pressures and requirements of practical farming. This is not helped when the Government changes the rules to reverse particular cases such as novel restrictions which have been on vermin control activity.

Provisions for compensation are either non-existent or inadequate where decisions are made that affect the income-earning capacity or capital value of assets. Such provision places a valuable discipline on government.

Because the rules are more stick than carrot, there are powerful incentives for landowners to undermine the purpose of the regulations. This is reinforced by the increasingly popular but farcical requirement for Net Gain of native vegetation cover whenever an application to clear is made. This principle inappropriately values native vegetation as an absolute good. The results are predictable:

- Many sound, beneficial clearing proposals are not put forward as the costs of regulation exceed the benefits to the farmer.

- Farmers tend to favour exotic species in tree planting to avoid future reservation for environmental purposes.

- New native forestry activities are discouraged for the same reason.

- Rare and endangered species of vegetation are concealed to avoid quarantining of productive land.

- Poor management practices (overgrazing of native vegetation) are encouraged in an effort to circumvent the restrictions.

ESTIMATING THE OVERALL COSTS OF REGULATION

In many ways regulation in Australia is less intrusive than in many other successful economies. Indeed, a recent World Bank analysis placed Australia as having the world's least intensive regulatory environment for starting a new business. Such measures, while useful are only partial and cannot incorporate all the facets of regulation that confront businesses.

Nobody seems able to come to grips with the total national expenditure on regulation in Australia. It is especially difficult to estimate the impacts of local rules and ordinances that impose massive indirect costs on farmers, miners and individual householders who want to build an extension or carport.

We do have regulatory review bodies, especially in Victoria and the Commonwealth that are trying to assemble compilations of the total number of regulations. From this the agencies will be able to move over time to estimating the change in regulatory intrusion and perhaps put some reasonable costs on the imposts. At present however, we have to rely on less direct measures.

Some estimates of the costs of US federal regulation have been made over a great many years by the Office of Management and Budget. For the latest year the gross cost was estimated at around 8 per cent of GDP.

Analyses of the cost of regulation in Canada and Mexico have shown comparable (though slightly lower) levels of costs as a share of GDP to those estimated for the US. Hence measures of the total cost of regulations in an economy like Australia's is likely to amount to around the 8-9 per cent of GDP seen in similar economies. Of course, regulation that more comprehensively stifles the market, as in the former Communist countries, has a far greater effect and brought GDP levels to only one third of those that might have prevailed.

CONCLUDING COMMENTS

There are disciplines that should be in place to ensure regulation is carefully considered and that a regulation once in place is neither the foothill for a new regulatory empire, nor even something that remains indefinitely.

On past evidence, these disciplines have not had much effect, at least on the overall level of regulation. It does seem very difficult to staunch the increase in social regulation. Risk aversion and a feeling on the part of most people that the direct impacts will be trivial contribute to this. Among the most pressing areas of new regulation is greenhouse with almost all academics and many politicians telling us we need to do more. One sobering aspect of the debate, which intensified with the recent release of the UK Stern Report, is that it comes on the heels of calls for insulating the Australian petrol market from world trends. Popular demand for action in one area often confronts the reality of implications elsewhere.

There are now increasing requirements for reviews prior to introduction of new regulations and for sunsetting. It does seem that these regimes are being increasingly taken seriously -- bureaucrats and politicians no longer argue that the market is faulty whenever it fails to accord with their expectations but the momentum especially for regulations with an environmental rationale is clearly very strong. The following are some recommendations that should be required prior to new regulations being introduced:

- Require a review to ensure the new regulation is fully consistent with the letter and spirit of the freedom of inter-state commerce provisions of the Constitution

- Introduce the regulation under a two stage process approach: the first simply setting out the issues in a dispassionate and non-committal, manner and the second seeking comment on the agency's preferred approach.

- Require an independent analysis to verify that the regulation is merited. This might be a scientific review in the case of measures mooted that guard against health or environmental externalities. And it may use formalised and independent economic analysis to review alleged economic benefits from an externality.

- Establish disciplines that ensure the regulatory burden does not increase. In this respect a useful approach would be that of the UK Prime Minister's direction to the Better Regulation Task Force to look at:

- First measuring the administrative burden then setting a target to reduce them (the Dutch approach) and

- A "one in, one out" approach to new regulation, which forces a prioritisation of regulation and its simplification and removal.

The Commonwealth Government has announced in response to the Rethinking Regulation report that it is stiffening its regulatory control procedures. New regulations as well as existing ones almost certainly add more costs than benefits. Measures that place impediments to their promulgation or facilitate their repeal should all be considered.

But if anyone thinks that it will be easy to put the brakes on regulation growth, just reflect on the NSW Government. On the day they released their IPART report on reducing the regulatory burden, they announced a new set of proposals to up the renewable energy burden on the state from 10 per cent of the total to 15 per cent. Gilding the lily they employed consultants to say the program would cost a trivial sum and the consultants even propose IPART as its regulator.