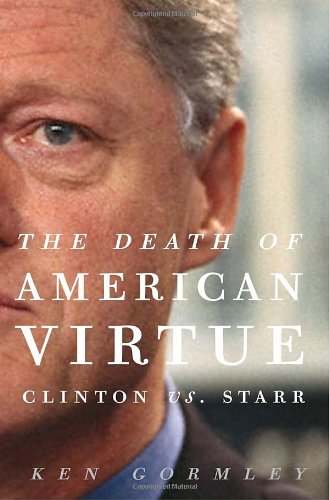

The Death of American Virtue: Clinton vs. Starr

by Ken Gormley

(Crown, 2010, 800 pages)

President Clinton lied on national television. He had, as the entire world now knows, a sexual affair with 22-year-old intern, Monica Lewinsky.

President Clinton lied on national television. He had, as the entire world now knows, a sexual affair with 22-year-old intern, Monica Lewinsky.

Had he merely lied about an embarrassing affair he would have joined the ranks of adulterous spouses, political or not, who throughout history have sought to cover up their conduct. And we can all make judgements about what we think of the affair and the lie. He did what many married men caught cheating on their wife would do, try the lie first and see if he gets away with it. Particularly since the wife in question is Hillary.

But Clinton did not merely lie to the media, the American public and his family; he lied under oath in a legal deposition. The deposition related to a lawsuit that every lawyer and judge urged its plaintiff to settle for lack of evidence -- a lawsuit that began when Paula Jones went up to meet Governor Clinton in a hotel room in May 1991.

Ken Gormley's definitive retelling of the events that culminated in the House of Representatives voting to impeach President Clinton makes for disturbing reading at times. But not perhaps in the way he intended. Gormley's thesis is that the activities of all parties to the events that led to the impeachment were somehow different to the way American politics was traditionally played.

The death of ''American Virtue'' of the title is supposed to be the virtue of democratic fair play. This is just not supportable. What about Nixon?

Despite this, Gormley has written an important book, important not merely as the definitive guide to the whole Lewinsky mess but also important for its insight into the American politico-legal system. And this system emerges with few credits to its name.

In the most chilling encounter of the book, staff of the Independent Counsel's office, along with FBI agents, get Linda Tripp to trick Monica into a meeting from whence she is whisked upstairs to a hotel room for six hours of interrogation. At the time, Monica was 24 years old.

Despite having the wherewithal to ask repeatedly for a lawyer, the questioning continued without one.

It is a sad reflection of the state of liberal democracy when it is apparently legal and acceptable to hold and interrogate a young person who at that time had done nothing illegal, was not suspected or accused of terrorism and, as well as asking for a lawyer, just wanted to speak to her mother. In response to this request, they then threatened to prosecute Monica's mother as well.

In a review of the Starr operations by the Justice Department, it was this ''brace'' of Monica that was highly criticised, yet this review was sealed indefinitely from public view by a judicial panel. The existence and contents of the Justice Department review is only public now because the author, former Justice Department lawyer Jo-Ann Harris, was so incensed she told Ken Gormley.

That Harris chose Gormley to release her report, an action that could leave her open to contempt of court, demonstrates the trust and access Gormley received from virtually all the major actors in this long-running drama. Only Hillary is absent from the roll call. And overall Gormley lets everyone speak for themselves.

Nobody comes out well.

This is a book of lawyers. Ken Gormley is a law school dean. It sometimes feels that he has never met a lawyer he doesn't like. And this highly process driven book takes some getting used to. Some sections read as verbatim recollections in real time. Sometimes the same series of events is recounted by different sides. And the sheer number of cases, appeals, reviews, investigations, and depositions is overwhelming.

A negative consequence of relying on insider interviews is that much sense of the broader reaction to these events is lost. For readers who lived through the whole Monicagate saga through the ubiquitous media reporting of it, this book seems utterly removed from the prurient tsunami reported across the world. At times this is jarring, presenting the actions of the Special Counsel's Office as beavering away in isolation for the truth, when the interaction of the media, the main actors and public opinion had a major impact.

Moreover, letting people tell their stories largely without comment, does on occasion leave too many questions unanswered. For example, Linda Tripp apparently edited the tapes she had of Monica and a number of people allude to there being a ''real'' story behind Ms Tripp's actions. Yet this is not pursued.

Despite these limitations, the meticulous recounting of every twist and turn, from Bill Clinton's meeting with Paula Jones through to President Clinton pardoning Susan McDougal on his last day in office, delivers its lessons better than any thematic or analytical approach.

In many ways, the tacts do speak for themselves even though this is such a highly contested story. And the lesson is not whether Clinton lied: he did. Or whether there a ''vast right wing conspiracy'' to bring down the Clinton White House. It appears there was.

Instead, the lessons are in timing and process. How a non-starter of a sexual harassment claim, a claim repeatedly thrown out by the courts, could end up as an impeachment trial in the US Congress. By fashioning a chronological tale based on ''he said, she said'', rather than analysing the broader political themes, there is ample opportunity to reflect on how everything could have been so different if not for some small and procedural decisions made along the way whose impact could not have been envisaged.

Overarching all these decisions and missteps was Ken Starr's initial decision to work as Independent Counsel on a part-time basis. Had he gone to work full-time to wrap up the Whitewater investigation, the start of all this, the whole thing would have been concluded well before Clinton met Monica. Instead, he spent three years rehashing Vince Foster's suicide only to conclude that it was, indeed, suicide.

Had Starr had any prosecutorial experience he would not have been waylaid by his overly zealous staff, some of whom had links to Republican and other figures on the right (such as Richard Mellon Scaife) who were bank-rolling side investigations and lawsuits designed to discredit the Clinton White House.

Had Paula Jones settled her case when her lawyers advised her to do so there would have been no deposition for Bill Clinton to lie to, no link between his affair with Monica, and no conflagration of Monica, Paula Jones, Whitewater and Vince Foster.

In the end, neither Ken Starr, nor his successor, Robert Ray, found a provable case against either Clinton in relation to their initial brief to investigate Whitewater. Despite years of investigation and tens of millions of dollars, no case that had a reasonable chance of securing a conviction could be proved. But this is not a defence of Bill Clinton. Clinton refused to settle the Paula Jones case despite all advice that doing so was the best political and financial response. Clinton lied about his relationship with Monica Lewinsky, and did so under oath.

If all the major players came out tarnished then it's without doubt the process that takes the greatest body blow. After it was all over even Congress realised it had unleashed a monster when it quietly chose not to reauthorise the order setting up the Office of Special Counsel. Apart from the ''brace'' of Monica, the overreach of law enforcement and judicial agencies for partisan purposes is a recurring motif.

Perhaps this is best illustrated by the approach by the Office of Independent counsel and the FBI to former Secret Service Director Lew Merletti two days before Clinton would vacate the presidency. According to Merletti an FBI agent threatened him with ''There's only one person left who can give us the President of the United States. And that's you. And we know that you were involved in a conspiracy with him, and we want to hear it today.'' There was no evidence; it was merely the theory of a partisan agent trying to make a name for themselves.

Through Monicagate the separation of powers seems to have been redefined, away from an idea that the judiciary is a brake on political power. Instead, the judiciary is presented as partisan and activist. Not activist in the sense of making law through cases but activist in the process.

Much of this is how Ken Starr chose to interpret his role -- as either a crusader for truth or a rabid zealot depending on your viewpoint -- but in any event as an investigator and judge combined.

No comments:

Post a Comment