Occasional Paper

REPORT OVERVIEW

The Gretley Mine Disaster

- In 1996, four miners died in the Gretley disaster in the Hunter Valley.

- The deaths occurred because the miners broke through into a water-filled disused mine which instantly flooded the mine in which they were working.

- The disaster occurred because the management of the company operating the mine had relied on maps of the disused mine provided by the New South Wales Department of Minerals Resources. The maps were faulty, showing the old mine in the wrong position.

- In 2000, the company that owned the mine and the managers of the mine were prosecuted and convicted under New South Wales' occupational health and safety laws. The company and the mine managers were convicted in 2005. The company was fined $1.47 million and the mine managers a total of $102,000.

Failure to prosecute re Gretley

- The Department of Minerals Resources was not prosecuted. The New South Wales Government has not revealed why prosecution was not commenced against the Department. The company that employed three of the men that died in the disaster was not prosecuted. The New South Wales Government has not revealed why prosecution was not commenced against the company. The company was a labour hire company that was majority-owned by a trade union.

- The failure to prosecute either the Department of Minerals Resources or the company that employed three of the miners, and the failure of the New South Wales Government to reveal why they were not prosecuted raises serious questions about the integrity of the occupational health and safety system in New South Wales and the use of the powers of criminal prosecution under the system.

The integrity of the occupational health and safety system in New South Wales is of particular concern given that there are provisions under existing legislation not only for the imposition of financial penalties, but also for "industrial manslaughter" and the imprisonment of individuals.

New South Wales Occupational Health and Safety laws

The Gretley disaster set in train a political process that led to new occupational health and safety legislation in New South Wales. These laws are seriously flawed because they:

- deny natural justice;

- apply presumption of guilt;

- reverse the onus of proof;

- permit a prosecution process that is not free of actual or presumed bias (in that prosecuting authorities have a financial interest in the outcome of the prosecutions); and

- allocate liability disproportionately.

They are laws built on a culture of hate directed toward employers. The laws contribute to unsafe work practices in New South Wales. The laws need to be changed urgently.

This report is the result of a two-year investigation and research project into New South Wales' occupational health and safety legislation. It draws entirely on information in the public domain. The report offers the views that:

- The design of NSW OHS legislation is deeply flawed. It creates dangerous work cultures in NSW because it is based on a presumption of guilt for some parties and minimal application of liability for others.

- The processes of prosecution or non-prosecution have suffered from serious irregularities, to the point that there exist questions about the integrity and impartiality of the OHS prosecution processes in NSW.

It cannot be ascertained through information in the public domain whether the prosecution processes in NSW are compromised. The absence from the public domain of key information raises fundamental concerns. Questions need to be answered.

GRETLEY: A NSW OHS DISASTER

1. SETTING THE SCENE: 1892

Imagine this: a mining surveyor is huddled over his desk in a small back office of a building somewhere in the Hunter Valley in New South Wales. Although we don't know the exact date or circumstances, it's some time around 1892. And although it's speculation, the following is what might have transpired.

The surveyor's supervisor walks into the room. It's near the end of the day. "Finish up", his supervisor says to him. "The company's gone broke."

"What?" the surveyor replies shocked.

"We have to leave now!" his superior continues.

"But my work, the maps, they're not finished", the surveyor implores.

"Leave them. The Mines Department officers will take over in the morning; they'll sort everything out."

Surprised and dumbfounded, the surveyor packs up his personal belongings and walks outside, locking the office door behind him. He's worried about his future but he's also concerned about leaving the maps and the fact that they are not fully finished.

It's been his job for several years to map the coal workings of Young Wallsend Colliery mine accurately. At its deepest, it operates at 460 feet underground. It's been a responsible and exacting job. Little does this surveyor know, however, that his uncompleted maps will result, some 100 years later, in the death of four miners in the year 1996.

Even more, the surveyor could not imagine that his unfinished maps would see laws passed and used in NSW which stripped people of their right to natural justice. He'd perhaps be surprised to find that the deaths resulted in a chain reaction in the processes of the law in NSW, to the extent that there are now significant questions relating to the integrity of the administration and application of the law in that State.

2. SETTING THE SCENE: 1996

At 5:30 am on 14 November 1996, some 460 feet underground in the Gretley coal mine in the Hunter Valley, four men died instantly. We can believe that they died instantly because when the wall of water broke through into the mine shaft in which they were working, the continuous excavation machine weighing 45 tonnes on which they were working was tossed some 17.5 metres back into the depths of the mine. The miners died not knowing that they had dug into the flooded Young Wallsend Colliery mine, closed over 80 years earlier.

These were four needless deaths which left families devastated and a community traumatised. There was grieving, particularly within the mining union -- the Construction Forestry Mining and Energy Union (CFMEU). One of the dead was a young man related to a senior official in the local branch of the CFMEU.

The four men's deaths initiated a review of work safety laws in NSW. The Gretley disaster was seen as the "straw that broke the camel's back". There had been too many deaths in coal mines in the Hunter Valley over the previous few decades. (1) Some of the disasters had involved more deaths than those at Gretley. But the situation did not seem to be improving. There were many official inquiries but nothing seemed to be changing. Gretley represented a watershed, and the unions, the CFMEU in particular, were determined that things would change.

In 2000 and 2005 new work safety laws were passed in NSW. The laws not only cover mines but all of NSW's work sites. However, instead of these laws being a positive legacy to the memory of the four deceased Gretley miners, they do an injustice to their memories. This needs to be corrected.

Instead of laws built on justice which improve the work safety of everyone in NSW, the laws are counterproductive and misconceived. These are laws designed to apportion blame to a culturally and legally defined group -- regardless of the facts of any situation. Further, these flawed laws have created a questionable process of prosecution (and on other occasions, a failure to prosecute).

3. WHAT SPECIFICALLY HAPPENED AT GRETLEY?

The Young Wallsend Colliery (the old Gretley) mine initially closed in 1892. The mine was later reopened sometime around 1907 and then closed again around 1912. When the mine was finally closed, it was sealed with a concrete cap placed over the top of the mine shaft. The mine shaft had been sunk to a depth of 460 feet from which the workings spread out to follow a coal seam.

It's not fully known why the old Gretley mine closed. Available records are scant. The mine had probably become uneconomic. The coal seam being excavated at Gretley was of lower quality than other available coal deposits in the Hunter.

There are numerous such old coal mines across the Hunter Valley. In the 1890s, the process of mapping mine shafts and diggings was highly developed. This continues to the present day. Shaft locations and diggings were mapped in exacting detail as was required under law and coordinated through the colonial Mines Department.

To understand how the disaster happened, 4 mine maps need to be understood. One map was drawn in 1892, another in 1909 and two maps in the 1960s.

1892:

The old Gretley underground coal workings were drawn on a map that was made in 1892. But this map was not completed and was confusing. It had two drawings of the mine workings overlaid one on the other. One drawing was in red and the other in black. What the two different coloured drawings meant was not explained on the map. It was deposited, as required by law, in the archives of the NSW mines department in the 1890s.

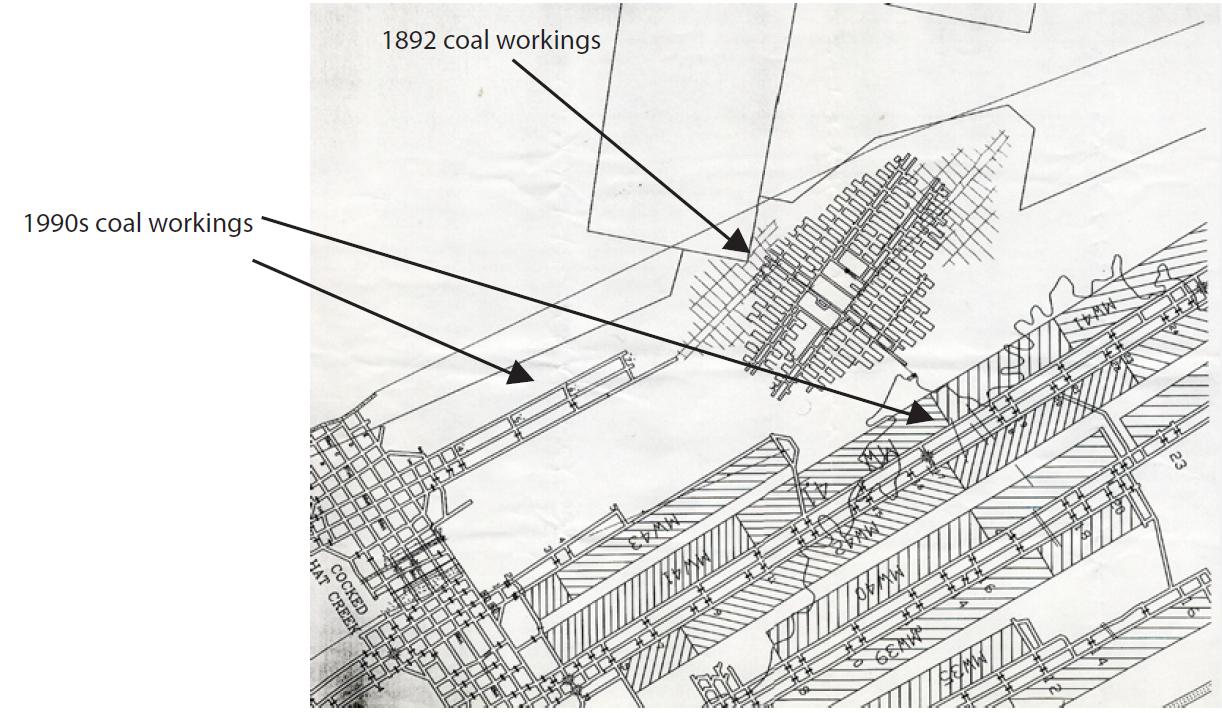

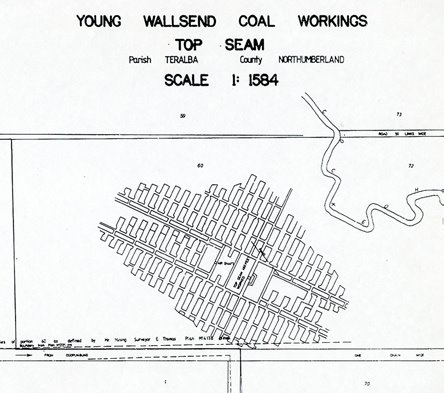

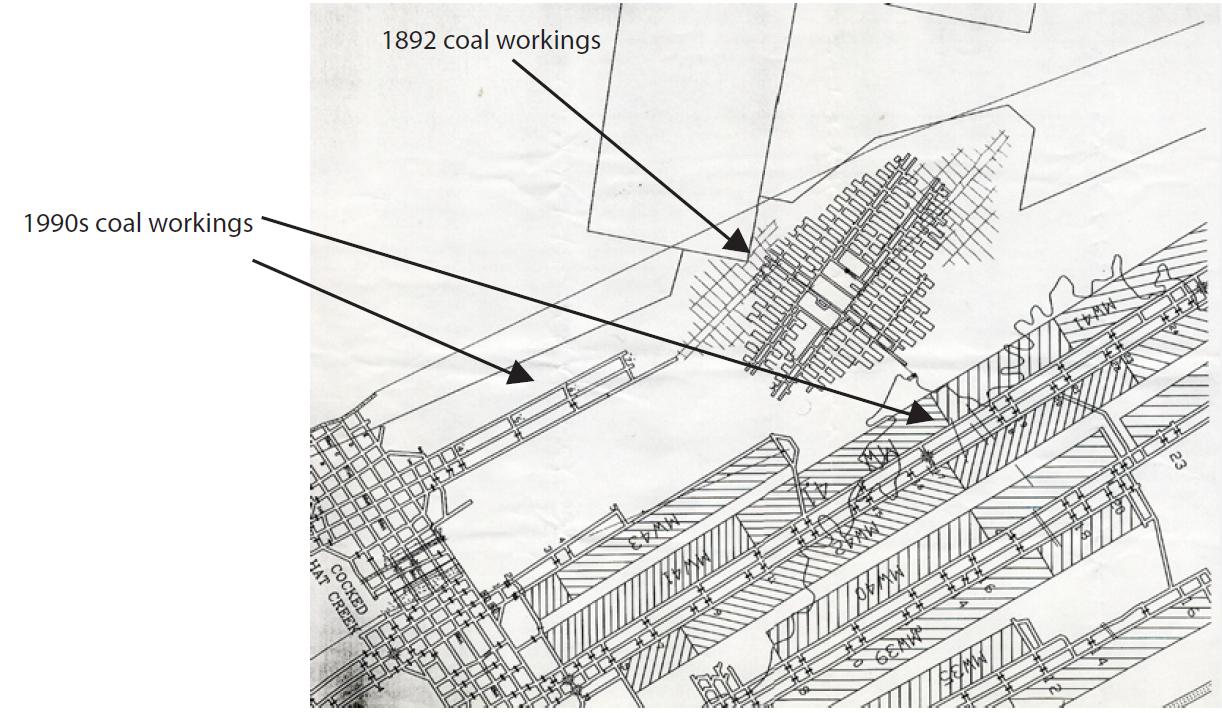

Map showing the old workings (overlaid) and new diggings. This map shows what the 1892 map looked like with the overlay of 2 drawings and the location of the 1990s' workings surrounding the old workings.

Source: Pers. comm.

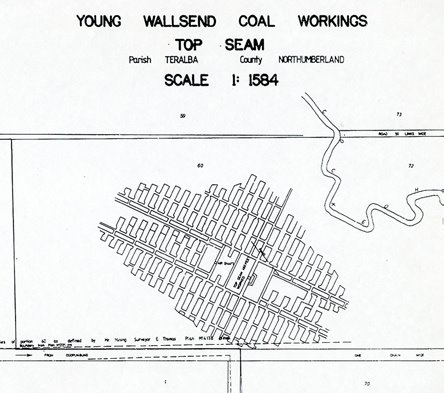

Faulty maps provided by the Department to the company, drafted in the 1960s, depicting two seperate layers of workings.

Faulty maps provided by the Department to the company, drafted in the 1960s, depicting two seperate layers of workings.

Source: Pers. comm.

1909:

Around 1909, the mines department reviewed the 1892 map and updated its records with a "skeleton tracing" and notes that clarified the 1892 map.

1960s:

At some unknown time, but probably in the 1960s, the NSW mines department reviewed the Gretley map and made a fateful error. The department took the 1892 map, and drew two new maps. Very significantly it appears that the 1909 map was ignored. The department applied an incorrect interpretation to the two coloured drawings shown on the 1892 map. They incorrectly showed two depths to the coal workings -- one at 521 feet depth shown in red and one at 460 feet depth shown in black. Each depth corresponded with known underground coal seams. However, in fact, there was only one working at the 460 feet coal seam. Of fundamental significance, the map which the department drew at the 460 feet depth showed the coal workings in the wrong position to an error of 100 metres.

The mines department effectively now had four maps in its files -- two from the 1960s which were faulty, one from 1892 which was confusing and the 1909 "skeleton tracing" which was accurate.

In 1994, the Newcastle Wallsend Coal Company Pty Ltd (the Company) -- a wholly owned subsidiary of Oakbridge Pty Ltd -- applied to the New South Wales Department of Mineral Resources (DMR) to mine the remaining un-mined coal seams around the old Gretley mine at the 460 foot depth. It is common practice for this to occur in the Hunter Valley. Geological surveys have accurately located the coal seams throughout the Hunter and assessed the quality of the mines. Digging into coal seams around old closed mines is common.

It is a legal requirement that the Company use the maps obtained from the Department. The Department must also approve all mining methods.

Instead of being given the four maps, the Company was given only two. The two maps they received were those maps produced in the 1960s which were wrong. The Company was not informed that there were two other original maps. In fact it appears that the original maps were "lost" somewhere in the archives of the DMR. (2)

Over a century or more, the old Gretley mine had filled with water. The water pressure contained in a mine shaft which was 460 feet deep and full of water was enormous.

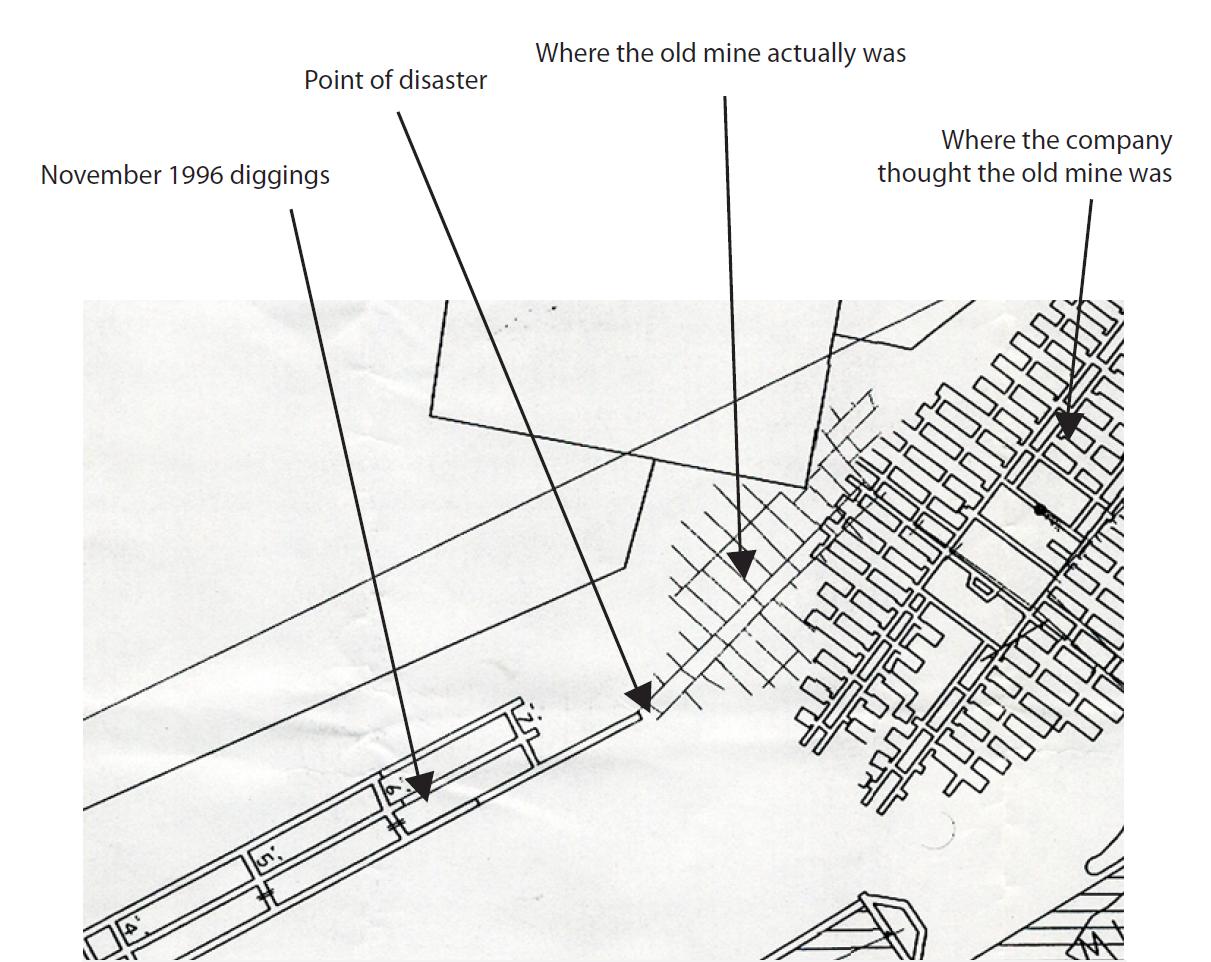

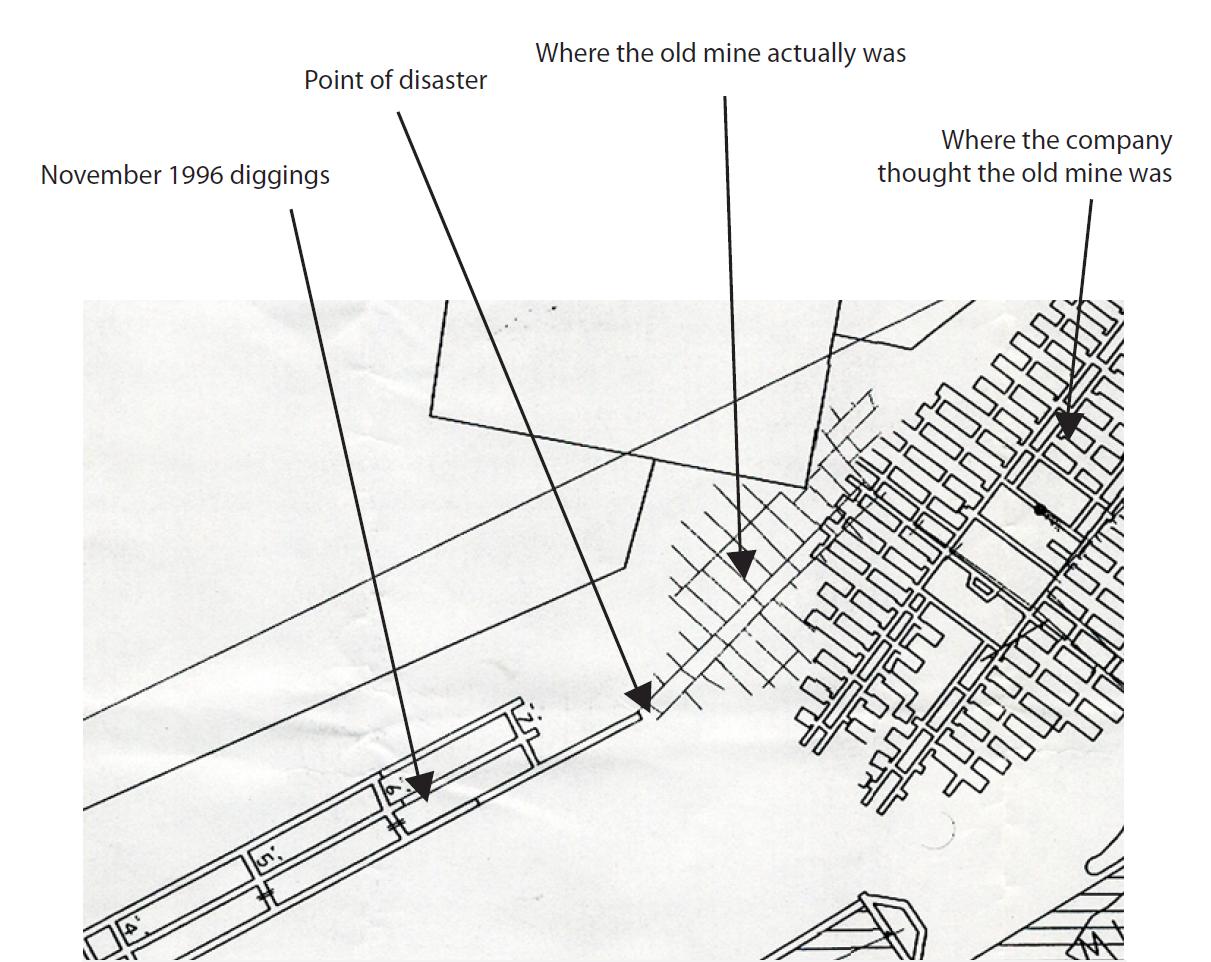

Map detail showing the point of disaster.

Source: Pers. comm.

The company's objective was to mine the existing coal seams around the old Gretley workings. The danger of catastrophic flooding was clearly understood. The alternative courses of action were to pump the old mine free of water or excavate around the old mine while staying a safe distance away from the flooded old shaft and workings, (that is, leaving a solid and sufficient barrier of un-mined coal). The decision was made to leave the mine shaft alone and to excavate around the old workings. The decision was approved by the DMR. This was accepted and common practice in the Hunter Valley.

Standard procedure and law required the Company's mine surveyor to investigate other sources of historical records to verify the accuracy of old mine maps. This was done. But the error in the two maps supplied was not identified. No research indicated that the DMR had two additional records in its possession. The DMR did not indicate that it had two additional records.

Mining proceeded. The Company followed accepted mining procedures that required new workings to stay a standard 35 to 40 metres away from the old workings as shown on the map. The Company did this and added further metres as a safety buffer zone. At the time of the disaster, the Company believed that it was 100 metres from the old workings. It also intended to drill extended probes deep into the coal seam before excavating. Such probes normally identify safety or other problems well before being reached. The probes would have normally detected an unmapped old mine. The Gretley disaster happened mid-week. The probes were scheduled to be done that coming weekend.

The new Gretley mine was known as a "wet" mine. It was located in an area with underground water seepage and required constant pumping of water to clear the seepage. Although it's a matter of significant dispute, before the disaster the Company claimed that no unacceptable levels of water entry into the Gretley mine were detected or recorded.

The disaster occurred on 14 November 1996 at 5:30 am. Four men were working in the mine. The coal seam between the old and new workings burst, creating an instant rush of water so fast and forceful that nothing could withstand its power. The great surge of water drained from the old mine shaft and created a powerful vacuum within the old shaft, as its top was sealed with concrete. The massive concrete cap covering the top of the old shaft burst and collapsed with such force that people at ground level believed an earthquake had occurred. It was a violent occurrence.

The disaster happened because the company had relied on the two maps that were made in the 1960s by the DMR. The true position of the old mine was 100 metres closer to where the company was excavating than was realised.

If the company had been in possession of the 1892 and 1909 maps, it would have discovered the error in the 1960s maps and not excavated into the old mine.

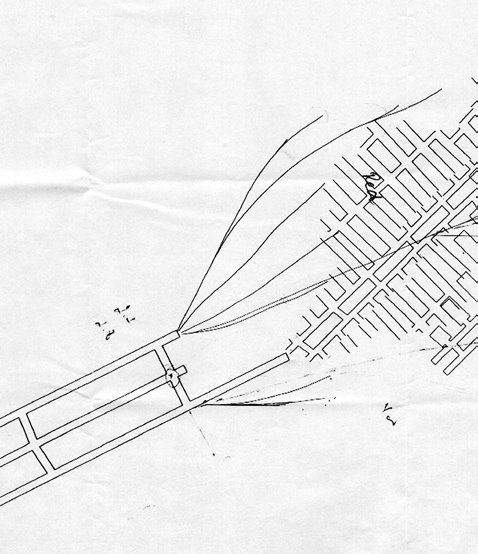

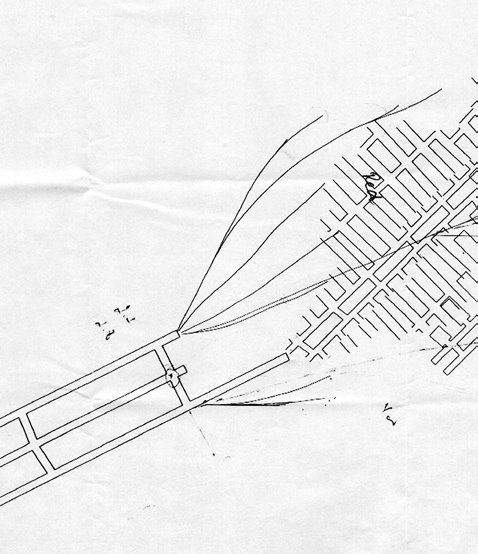

The intended probes

Just days after the disaster happened, the digging was to stop to send out "probes". These probes would have discovered the presence of the old water-filled mine.

Source: Pers. comm.

4. THE INVESTIGATION AND FORMAL FINDINGS

The immediate reaction to the disaster was shocked disbelief. The Company managers were traumatised, as were all the workforce and families. In these tightly knit mining communities, everyone knows everyone else. Within a few hours of the disaster the water had drained from the mine and it was declared safe enough for investigators to enter. Upon entering the mine the investigators immediately discovered the truth. They were able to enter the old mine workings. Yet according to the Department's maps, these old workings were supposed to be some 100 metres further away. Only then was it clear that the maps were faulty.

The NSW Government established a formal judicial investigation into the disaster, which reported in 1998. A coronial inquiry followed. In 2000, prosecutions were launched against the Company and several mine managers.

In the Formal Investigation (1998), the existence of the key old Gretley mine maps was revealed toward the end of the inquiry. The judge ordered the Department on several occasions to search its archives and investigate if there were other maps. Eventually the Department located the, until then, unknown original 1892 Gretley mine map. Further demands from the Inquiry revealed the 1909 sketch tracing. This was the missing piece of the jigsaw that exposed the errors in the maps supplied to the Company. The confusing 1892 map was made public. But apparently, and for some unknown reason, the 1909 sketch tracing, the one that explains the confusing 1892 map, has never been made public.

The Formal Investigation of 1998 was required to investigate the disaster under the powers and requirements of the Coal Mines Regulation Act 1982. This Act specifies the duties of each manager in a mining company and the Department. The Report found a series of shortcomings in the performance of the Department and the Company. According to the report, shortcomings were identified at every level of management in the Company.

The 750-page Report found that:

- The Department created the erroneous maps and did not exercise due care in relation to the maps.

- The Company managers did not conduct sufficient historical research and should have discovered the errors in the maps supplied by the DMR.

- There were indicators in the mine of increased levels of water days before the disaster that should have alerted the Company that there was something wrong. The Company disputed this.

The Report stated

The evidence before the Inquiry has demonstrated serious shortcomings in the performance of the Department of Mineral Resources, in the context of Gretley, and that of the mining company, The Newcastle Wallsend Coal Company Pty Ltd. In the case of the mining company, the shortcomings were widespread. (3)

In summary, the Report stated that procedural failures on the part of both the Department and the Company led to the disaster.

5. COMMENT

The disaster and the needless deaths of the four miners were the result of a long line of human errors over more than one hundred years. The errors were an accumulation of personal failures on the part of a number of people.

- The original mine map in 1892 was not completed. There were failures in the responsibilities of unknown persons who most probably worked for the Young Wallsend Colliery.

- Further, unknown persons in the colonial mines department/s failed to detect and correct the lack of completion of the confusing map in 1892. Instead the map was archived.

- In 1909, persons in the mines department moved to correct the confusion of the 1892 map. They did this with the skeleton tracing of 1909 and notes, but allowed the 1892 map to retain its confusing features. These were archived.

- Unknown person/s in the department in the 1960s created two new maps based on the confusing original 1892 map and it appears they failed to take proper note of the 1909 skeleton tracing. It is possible that they may not have even seen the 1909 skeleton tracing. They incorrectly created and labelled two newly separated maps. Other unknown persons in the department failed adequately to supervise this process and detect the errors. It would appear that the old (1892 and 1909) and new (1960s) maps were separately archived without the new maps having reference to the original 1892 map or the 1909 skeleton tracing. Some unknown person/s failed in their archival responsibilities.

- In the 1990s, unknown person/s in the DMR supplied the Newcastle Wallsend Coal Company with only the two new, but faulty, maps from the 1960s and failed to identify, discover and supply the original 1892 and 1909 map/tracing to the Company.

- Known persons (according to the Formal Investigation) in the Newcastle Wallsend Coal Company failed to undertake adequate historical research and failed to investigate adequately the 1960s' maps so as to discover the errors made over the last one hundred years and to uncover the original map and tracing in the DMR's archives.

- According to the Formal Investigation, known officers of the Company failed to interpret the increased level of water in the mine in the days before the disaster as an indicator that the maps were faulty.

Who, then, was to blame? What was the result of the prosecutions?

6. PROSECUTION OF THE COMPANY AND MANAGERS

Following the Formal Investigation Report, a coronial inquiry was conducted.

Prosecutions against the Company and several mine managers were launched in 2000. The prosecutions were of a criminal nature and conducted in the New South Wales Industrial Relations Court under the provisions of the Occupational Health and Safety Act 1983.

Under the Occupational Health and Safety Act an employer was obliged to ensure a safe workplace. The word "ensure" in the Act imposed on employers an absolute obligation for safety of a god-like nature. That is, the Act provided that employers are automatically "guilty" simply because a workplace safety incident occurs. The Act read:

Employers

8(1) An employer must ensure the health, safety and welfare at work of all the employees of the employer.

That duty extends (without limitation) to the following. ... (4)

In other words, the Act works with a presumption of guilt as opposed to the normal presumption of innocence to which we are all accustomed under criminal proceedings. With the presumption of guilt, an employer must disprove guilt.

Further, the Coal Mines Regulation Act 1982 identifies specific mine manager positions where the holder of those positions also has statutory strict liability for safety.

The prosecution of the managers relied on the fact that they were identified as having statutory total liability because of their managerial positions as described under the Coal Mines Regulation Act. This identified them as being totally liable under the OHS Act as well. Consequently, the managers were also presumed to be guilty and had to disprove their guilt.

In addition, the prosecution process is conducted in the NSW Industrial Relations Commission rather than in the courts. Final decisions of the NSW Industrial Relations Commission cannot be appealed. This is unlike any similar in NSW or in Australia.

At the time of the 1996 disaster, the Newcastle Wallsend Coal Company Pty Ltd (Gretley mine) was owned by Oakbridge Pty Ltd. By the time the convictions were recorded in 2005, the international mining company Xstrata had purchased Oakbridge. Xstrata did not have shareholdings in Oakbridge at the time of the disaster. Convictions against Xstrata and four mine managers were recorded in March 2005. A fine of $1.47 million was imposed on Xstrata and fines totalling $102,000 on three managers. Even though the NSW Industrial Relations Act prohibits appeals against decisions of the Industrial Relations Commission Xstrata is attempting to appeal against the convictions through other processes.

By purchasing Oakbridge, Xstrata inherited total responsibility for the criminal liabilities of Newcastle Wallsend Coal Company Pty Ltd in relation to Gretley.

7. COMMENT

It is clear that the Gretley disaster was the culmination of a series of human errors over a long period of time. Many of the people responsible for the errors are no longer alive. The Gretley mine managers and Company were at the tail, but most critical, end of that series of errors. They alone were prosecuted.

The OHS Act in NSW is unlike any other OHS legislation in Australia because it alone applies presumption of guilt responsibilities on employers. All other OHS legislation in Australia complies with international OHS standards through which employers and all parties at workplaces are held responsible for what they "reasonably and practicably control". Presumption of innocence applies. These international standards are orientated to ensure justice for all responsible parties.

Given the serious nature of the charges and potential consequences for breaches of the NSW OHS legislation it is completely inappropriate that the NSW Industrial Relations Commission be the forum for the hearing of prosecutions. Industrial relations institutions such as the IRC have embedded within them a mindset that considers workplace warfare along class lines to be a reality. This is the environment of industrial relations disputes. But it's an inappropriate environment for criminal-type prosecutions as occur under the NSW OHS Act.

If the Gretley disaster had occurred in a State other than NSW, the process of prosecution would have been very different. The prosecuting authority would have had to prove, on the evidence, that:

- the company and managers had acted unreasonably;

- the situation was something over which they had control; and

- they had failed to do everything practicable to prevent the disaster.

It is entirely possible that convictions could still have been recorded under these circumstances. But that is speculation. What would clearly have been different, however, is that the Company and its managers would have faced a very different legal process in which:

- they were presumed innocent; and

- the prosecution would have had to prove guilt.

These are the natural entitlements to justice expected by everyone in the Australian community.

In the Gretley prosecutions, these natural entitlements to justice were denied.

8. FAILURE TO PROSECUTE THE DEPARTMENT

The Formal Investigation of 1998 found that the Department of Mineral Resources directly contributed to the disaster through its failures in relation to the maps. However, the Attorney-General of NSW, Hon. Jeff Shaw, refused to initiate a prosecution against the Department and would not make public the reasons for not prosecuting. (5) The NSW Government has never made those reasons public.

The legal representative for the dead miners' families has stated that he believed that the Department could have been convicted for being a direct cause of the disaster. (6) The Government was criticised in the NSW Parliament for failing to prosecute the Department. (7) The CFMEU believed that the Department was culpable:

"... we regard the Department of Mineral Resources as equally culpable as the company in those deaths ..." (8)

9. COMMENT

Given the findings of the Inquiry that indicated that the Department contributed to the disaster, at the very least there should have been a full public explanation as to why the Department was not prosecuted. The Department:

- Failed to properly archive the 1892 map and 1909 sketch tracing so that these could be easily retrieved.

- Made calamitous errors in the drawing of two maps in the 1960s, and failed to cross-reference these to the 1892 and 1909 documents in its possession.

- Failed to archive all four documents properly so that these could be easily identified and retrieved.

- Made a massive error by supplying only the 1960s maps to the Company in the 1990s.

- Failed to notify the Company in the 1990s that it had two other critical documents in its possession.

Failure to prosecute the Department raises serious concerns. In the absence of the Government's supplying reasons, serious questions are raised.

It appears that the critically important 1909 skeleton tracing has not been made publicly available. Why not? According to the Inquiry, the 1909 sketch tracing is the key to understanding the maps. The question must be asked: would the contents of the 1909 skeleton tracing indicate that the Department was not merely incompetent but also culpable? We do not know.

Why was the Department not prosecuted? One possibility is that because the structure of the NSW OHS Act applies total liability to the designated employer, that persons or organisations specifically outside the employer's managerial circle may not have statutory obligations in the matter. If this were the case, however, it would mean that the Department escaped prosecution because of a technical legal failing in the OHS Act. This would indicate a serious flaw in the OHS Act that should have been corrected to enable Departmental prosecution.

While the Government keeps secret its reasons for non-prosecution, suspicion will necessarily be raised on several levels about the integrity of the OHS prosecution process in relation to Gretley.

If workplace injury and deaths are to be avoided, it is essential that every person and organisation in any chain of events that leads to safety incidents is captured in the liability net of OHS legislation. The NSW OHS legislation has an excessive and almost exclusive focus on holding employers or "like-employers" (for example, mangers) responsible, while other parties are not held similarly liable. This is flawed legislation that contributes to unsafe worksites and practices.

If the failure to prosecute the Department is a result of failings in legislative design, then the Gretley disaster stands as a key demonstrator of flawed OHS legislation in NSW.

10. THE CFMEU

The Gretley disaster and subsequent prosecutions and convictions cannot be properly understood unless they are considered within the framework of the political and industrial agitation of the mining union, the Construction Forestry Mining and Energy Union (CFMEU). Further, the commercial and legal involvement of the CFMEU in the mining activities at Gretley exposes concerns about the integrity of the prosecution process that have not, so far, been explored.

The CFMEU was the union with coverage of the Gretley mine. It is one of the wealthiest and most powerful unions in NSW. It has deep institutional links with the Government. It has significant influence over the political pre-selection processes of many members of parliament. It is a large financial contributor to the Australian Labor Party. It has representatives sitting on a vast array of Government advisory and regulatory bodies as well as involvement and financial stakes in commercial activities. It uses its connections to lobby fiercely for its political, industrial, commercial and policy objectives. The CFMEU has a long history of running aggressive but passionate campaigns on OHS policy. None of this is underhand, secret or illegitimate.

But it appears that these connections to the Government have given it significant influence over the design of NSW OHS laws. Its influence extends to the prosecution process under OHS laws. Under the OHS Act of 2000, the CFMEU, as well as other NSW unions, has the power to conduct prosecutions under the Act and to retain half of any fines imposed. The CFMEU is an OHS prosecuting authority.

11. THE CAMPAIGNING OF THE CFMEU AFTER GRETLEY

Following the Gretley disaster, the CFMEU dedicated itself to campaigning for the prosecution of the Company and managers at Gretley. Its campaigning was highly public, visible, political and emotive. Material on its Website is testimony to its campaigning. (9) The emotion was understandable.

The CFMEU and the deceased miners' families had to wait some five years after the disaster for the prosecutions to be launched.

After the prosecution was launched, it ran into technical difficulty because the wrong Minister had signed the prosecution papers. (10) The CFMEU agitated and pressured the Government strongly to amend legislation to enable the prosecution to proceed. In December 2003, the Government passed retrospective legislation to overcome the technical problem.

The CFMEU was outraged when Xstrata announced that it would appeal against the convictions. It threatened industrial action and conducted rallies against Xstrata's appeal. One CFMEU headline read "Mining companies should not be allowed to get away with murder in NSW". (See Appendix B.) The Gretley deaths were not murder, but this headline demonstrates the highly charged emotional atmosphere surrounding the quest for convictions.

12. THE CFMEU AND THE LABOUR HIRE COMPANY UMSS

United Mining Support Services (UMSS) is one of the oldest labour hire companies in NSW and supplies workers to mines in NSW. As a traditional labour hire company, the workers supplied are, at law, employees of UMSS. UMSS is a legal employer.

Three of the miners who died in the Gretley disaster were employees of UMSS. (See Appendix C.)

It is normal and expected in OHS incidents where the workers have been employed or engaged by a labour hire firm that the labour hire firm would be subjected to extensive and rigorous investigation about its OHS approaches and whether or not it had liabilities under the relevant Act. Prosecution of labour hire firms under OHS legislation is a regular occurrence around Australia.

Labour hire firms are effectively part of the managerial processes of the companies for whom the workers work. Labour hire firms are clearly and ordinarily in the OHS liability ambit under all OHS legislation in Australia.

In the case of Gretley, UMSS was the legal employer of three of the deceased miners. Under the NSW OHS Act, the "employer" has a statutory total obligation for safety. As we have already seen, presumption of guilt applies automatically to the employer.

In the 750-page 1998 Formal Inquiry into Gretley, the only reference to UMSS is one paragraph stating that UMSS employed the miners. The 1998 Inquiry report said, "Three of the four men who died ... were contractors supplied by the United Mining Support Services Pty Ltd". (See Appendix C.) No detailed investigation of UMSS can be found in relation to the Gretley disaster.

UMSS was not prosecuted over the deaths of the three Gretley miners it employed.

UMSS was majority-owned by the CFMEU. (See Appendix D)

A director of UMSS at the time of the Gretley disaster subsequently became Chairman of UMSS and held positions in the CFMEU of Vice President, then President, of the Northern District of the CFMEU NSW, is on the Committee of Management of the National Office of the CFMEU and General Secretary of CFMEU Mining and Energy Division. (See Appendix D)

Some time around mid-2005, UMSS was sold to TESA, a Tasmanian-based labour hire firm. In August 2006, the Skilled Group (a listed labour hire business) announced its intention to acquire TESA.

13. COMMENT

The apparent non-investigation of UMSS and its non-prosecution over the Gretley disaster raise serious concerns and questions about the OHS prosecution process in NSW.

As the direct employer of three of the deceased miners, it would normally have been expected that there was a statutory requirement under the NSW OHS Act for the prosecuting authority, at the very least, to undertake a detailed investigation of UMSS in relation to the disaster. Presumption of guilt should have applied to UMSS. What should have been investigated and placed on the public record was a detailed account of:

- the managerial role that UMSS played or should have played in the Gretley mine;

- whether UMSS had satisfactory OHS procedures in place in relation to its employees in the Gretley mine and whether the procedures were followed in relation to the Gretley disaster;

- whether UMSS, as the employer, had a statutory liability for the disaster under the OHS Act; and

- the reasons for not prosecuting UMSS, given that a prosecution did not occur.

Given that, on the face of it, UMSS was not investigated, and given that it certainly was not prosecuted, serious issues arise about the integrity of the NSW OHS Act and the application of the prosecution process. To put it starkly:

- Xstrata was prosecuted even though it was not the legal employer of any of the miners at the time of the disaster. It later inherited the status of employer of one of the miners when it acquired Oakbridge.

- UMSS was not prosecuted even though it was the legal employer of three of the miners at the time of the disaster.

There are questions that need to be answered:

- Given that the NSW OHS Act apportions total liability to employers, unlike any other Australian State, why was UMSS not automatically prosecuted along with Xstrata?

- Did the fact of the CFMEU's majority ownership of UMSS have anything to do with the apparent non-investigation and non-prosecution of UMSS?

- Did the CFMEU's intimate political affiliation with the ALP Government have anything to do with the apparent non-investigation and non-prosecution of UMSS?

- What guarantees are there that the process of the application of OHS laws in NSW is separate from, and independent of, the political process in NSW?

- Is the process of the application of OHS laws in NSW separate from, and independent of, the CFMEU in NSW?

- Given that the CFMEU has the power to undertake OHS prosecutions in NSW, that it has high-level political connections and conducts commercial activities as an employer in NSW, does the CFMEU have serious conflicts of interest in relation to Gretley?

NSW OHS: BEYOND GRETLEY

There are many questions that need to be answered about Gretley in relation to the OHS prosecution process in NSW. But it doesn't stop at Gretley. Gretley and its aftermath seemed to create more situations which themselves raise questions that need addressing. In retrospect, Gretley represented a watershed in NSW OHS prosecution processes.

14. POWERCOAL CABLE SNAP

Powercoal was a NSW Government-owned operator of some seven underground mines. It was the largest supplier of coal to NSW electricity generators, but was not performing well.

By way of background, in March 1998, along with considerable other activity, the CFMEU made representations to the NSW Premier concerning the viability and future of the Powercoal mines. (11) In August 2002, the Government sold Powercoal to Centennial Coal for $306 million. (12)

However, on 6 May 1999, a serious OHS incident occurred. Four men were inside a mine transport vehicle in the Wyee, Powercoal underground coal mine. The mine shaft was on an incline. The cable snapped. Three men jumped clear. One man rode the runaway vehicle 150 metres to the bottom of the shaft and suffered cuts and bruises. It was sheer luck that no one was seriously injured or killed.

This occurred some two years after the Gretley disaster and not that long after the Gretley Formal Inquiry had released its report. There were allegations that the cable snapped because of poor maintenance. On a simple reading of the events it would seem clear that Powercoal should have been prosecuted. However, this was not to be the case as a result of an extraordinary sequence of events. Effectively, Powercoal (the NSW Government) was not prosecuted because of "lost" paperwork.

The process of this "non-prosecution" was as follows (from Morrison v Murray) (13):

- For the government to prosecute itself, government approval is required. Premiers Memorandum No. 97-26 states that "Litigation involving Government Authorities requires consultation where prosecution of government agencies is contemplated". (s9)

In March 2001, the Department of Minerals Resources (DMR) recommended that Powercoal be prosecuted.

- In April 2001, Powercoal entered consultations with the DMR. (s18)

- The DMR subsequently issued summons for prosecution against Powercoal and made a Ministerial Submission to prosecute on 3 May 2001. (s25)

However

- "Contrary to the Department's usual practice, signed copies of the 'Consent to Institute Proceedings' forms were not attached to the Applications." (s29)

As a result, the Court found that

- "there has not been a valid Consent to Institute Proceedings ... and therefore [this Court] has no jurisdiction to hear the Application"

In other words, failure to lodge the correct paperwork resulted in the Minister not giving approval for the government to prosecute itself. In addition, there was also a failure to lodge the correct forms accompanying the paper work. Further, the appropriate paperwork was lost.

- "... neither the originals nor copies of the forms could be produced ..." "no contemporaneous memorandum was produced which reliably explained the loss of the forms ..." "no explanation was offered". (s31)

The Court found that there was not sufficient consent (from the Government) to commence a prosecution against Powercoal (the Government). However, there was sufficient consent (from the Government) to commence prosecution against three senior executives of Powercoal.

15. COMMENT

Given the sequence of events at Gretley and the comments made by the Gretley Formal Investigation, the failure of the DMR to lodge the correct forms in relation to Powercoal is astounding. Remember, it was the DMR itself which was heavily criticised in the Gretley Formal Investigation for having a poor and sloppy attitude towards OHS prosecution.

Returning to Gretley, in December 2003, the NSW Government rushed through retrospective legislation because the wrong Minister had signed the Gretley prosecution papers. The Government was quick to correct a technical problem in relation to Gretley, yet allowed a problem in paperwork in relation to a prosecution of the Government itself to block the prosecution of Powercoal.

Some relevant questions are:

- Was the Government's failure to prosecute Powercoal intentional?

- Did the matter go to Cabinet and, if not, why not?

- If the matter did go to Cabinet, why did Cabinet not take urgent action similar to Gretley -- viz., retrospectively correct the error and prosecute Powercoal?

The failure to prosecute raises serious concerns about the integrity of the OHS prosecution process in NSW.

Consider, also, the position of the three executives at Powercoal. The company they worked for (the Government) was the legal employer of the worker who was injured in the cable snap incident. A Government "error" in loss of paperwork enables the Government to avoid prosecution. Yet the same "error" in paperwork did not occur in relation to the prosecution of the executives.

Consider, too, Xstrata, who was not the employer at the time of the Gretley disaster, yet because it has subsequently fully acquired the Company, it carries the burden of being criminally prosecuted for the flaws of the previous Gretley employer. Yet in relation to the cable snap at Powercoal, the employer at the time (a wholly owned government company) avoids prosecution because the Government itself fails to ensure correct Ministerial and Cabinet procedures to effect the prosecution.

The quite obvious double standards here are a cause for great concern. It is hard not to think that the process of OHS prosecution in NSW has become heavily compromised and unreliable. Tragically the laws are not about the achievement of increased work safety. Instead the laws are about revenge; an eye for eye.

It must also be noted that Powercoal was prosecuted for the death of a coal miner in July 1998 at the Awaba Colliery. In that incident, a roof cave-in caused the death of a miner and Powercoal was fined $200,000. A mine manager, being "a person concerned in the management" of Powercoal, was found personally liable for Powercoal's offences. (14)

16. THE FLAWED STRUCTURE OF NSW OHS LAWS

The NSW OHS laws themselves are fundamentally flawed. This of itself leads to a distortion of prosecution processes. No other Australian State has OHS laws like NSW's. NSW is arguably on its own in international terms with its OHS laws. And it is clearly in breach of the internationally accepted principles of OHS legislation.

The core internationally accepted structure for OHS laws is that all persons involved in work are held liable and responsible for what they reasonably and practicably control. This structure, which is most clearly delivered in the current Victorian OHS laws, ensures that all parties who may have been involved in a workplace incident are held responsible. Employers, employees and anyone else involved in a worksite are held proportionally liable over the matters that they control. This ensures that all parties regard the process as fair because individuals are not found guilty for things beyond their control.

NSW OHS laws do not follow this model, but rather take a completely different and narrow approach in relation to liability and blame.

NSW OHS laws have a highly narrow focus on the role of the employer. Instead of equally apportioning liability and responsibility across all persons involved in worksites, the NSW OHS laws place emphasis on employers and, by comparison, apportion little if any liability to employees. For example, NSW OHS laws apply maximum fines of 750 penalty units and possible imprisonment against employers, but only 45 penalty units and no imprisonment against employees. Victoria, on the other hand, applies exactly the same level of penalties against both employers and employees.

In addition, NSW is alone in applying a presumption of guilt to employers. The mere fact that an incident has occurred means that an employer (or the employer's manager) is automatically held to be guilty. The presumed guilty person is in the position of having to disprove their guilt. And the Gretley case shows that even if others were also at fault, those others can and do avoid prosecution and conviction.

The Powercoal "roof collapse" case (the second Powercoal case mentioned above) shows how automatic guilt applies in NSW OHS laws.

In declaring Powercoal guilty, the Court said:

- The legislation requires that "every employer shall ensure the health and safety ..." (Powercoal & Lamont v NSW IRC & Morrison, 2005) (15)

- Hence, "The duty imposed on an employer to ensure health and safety at work of employees is absolute" (s28,1) and "to be construed as meaning to guarantee, secure or make certain ..." (s28,2)

- "The duty cast on an employer ... is not necessarily satisfied by carrying out what ought be done by a reasonable or prudent person in the circumstances ..." (s28,4)

- "The commission of an offence does not require the demonstration by the prosecutor that particular measures should have been taken to prevent the risk ..." (s28,9)

- "There is no warrant for limiting the detriments to safety contemplated by the statutory duty to those which are reasonably foreseeable." (s28,10)

That is, when it comes to establishing "beyond reasonable doubt" findings under the NSW OHS Act, the Full Bench found that, in relation to Powercoal, "In fact the roof fell in and killed Mr Edwards thereby putting beyond any reasonable doubt that the corporate respondent failed to obviate the risk to employees working in the relevant area." (s64)

This is a statutory perversion of the idea of justice involving "beyond reasonable doubt" normally available to an accused. It is achieved by legislative linguistic trickery in the OHS Act.

Further, the OHS laws enable managers to be held responsible for the guilt of the employer business. In the case of Powercoal, for instance:

- "Mr Foster was charged with two offences on the basis that, as the manager of the mine, he was deemed to have committed the offences of Powercoal ..." (s19)

- "50(1) Where a corporation contravenes ... any provision of this Act ... each director of the corporation, and each person concerned in the management of the corporation, shall be deemed to have contravened the same provisions ..." (s19)

17. COMMENT

A system of predetermined guilt from a culture of class conscious hate.

The NSW OHS laws are indeed odd, but also dangerous. By disproportionately apportioning guilt to one player in the work environment (the employer), the laws fail to require all players in the work environment to maximise their focus on safe behaviour. This creates the circumstances for dangerously unsafe work environments. It distorts behaviour and sets up circumstances of injustice. It encourages corruption of the processes of prosecution.

How did this come about? The Gretley case is important because it gives a window into the culture that created these laws.

If the NSW OHS laws had been the same as Victoria's at the time of the Gretley disaster, it is still possible that the company and managers could have been prosecuted. But they would not have been prosecuted on their own. It would have been possible, perhaps likely, that the Department of Mineral Resources and UMSS would also have faced prosecution. The investigations and prosecutions would have been much wider and fuller in seeking the truth and applying liability. Further, none of the parties would have been presumed guilty. A court would have been required to look at all the facts and make judgments based on whether parties had acted reasonably and practicably within what they were able to control. Guilt may still have been found on the basis of those facts. Full appeals would have been available.

But under the NSW laws, guilt was applied narrowly and selectively and the process omitted to hold responsible all possible players. This is plainly wrong.

Why this occurs in NSW is linked, it appears, to a strong cultural mind-set amongst politically influential sections of the NSW community which asserts that employers are all-controlling when it comes to operating businesses. This is the core belief (amongst a cluster of related beliefs) that drives and focuses all industrial relations laws and processes. For some reason, this belief pervades and is ingrained in the political culture of NSW like no other state in Australia.

Connected to this belief is another which suggests that because employers are all-controlling, they are also uncontrollably greedy and will exploit people and resources to achieve their singularly focused desire for money. And allied to this is the claim that state-imposed systems are a moral necessity to constrain employers. Further, that managers who control the systems of the employer businesses are totally responsible for the actions of the employer. In other words, that the employer is a collective entity operated by managers.

In this context, employers and managers are always viewed as inherently evil because they will do harm to workers if not constrained by laws that are so tough that employers have little chance of avoiding a guilty finding. That is, the laws are designed to produce a Star Chamber environment in which employers have little chance of being found innocent.

And this belief system, or mind-set, is held in NSW in many quarters with a passion and fervour that blinds the holders of such views to many alternative views. This passion and fervour is particularly evident in the CFMEU in the coal mining sector in the Hunter region of NSW. If flows out of the Hunter union movement to dominate the official organs of the union movement through NSW. A reading of material produced by unions in New South Wales, in particular that of Unions NSW and the CFMEU, will reveal a style of writing and expression that is full of passionate hatred and vitriol directed toward employers. (see Appendix B.) It is backed with huge volumes of academic publications that supply a veneer of argumentative credibility.

The accusation of "murder" in the Gretley disaster by the CFMEU (referred to above) is but one example of this mindset.

And because the union movement of NSW is so deeply connected to the NSW division of the Australian Labor Party, this belief system is deeply ingrained in the political culture of the State ALP as well as the union movement. It is ingrained to an extent like no other in Australia. And because the NSW ALP has been so supremely politically successful in NSW for so long, the belief system has moved out of the ALP to be almost accepted as truth within many elements of the broader community. It has become a near-dominant mindset within political orthodoxy in NSW.

It is out of this belief system and the political culture accompanying it that the NSW OHS laws emerged.

The laws display every element of the belief system which holds that the employer is by nature evil and must be punished if and when harm occurs to a worker. This is the only reasonable explanation for the nature of NSW's OHS laws. The laws do not take as their starting point a neutral stance as to who may be at fault in any OHS incident, then investigate the facts to apportion liability based on the facts. The NSW laws are deliberately structured in a way that the employer is presumed guilty simply because an OHS incident has occurred.

This is a particularly ugly approach to the design of law. It is law that deconstructs core foundations of civilised societies. It is law that is not only dangerous in terms of promoting unsafe work environments but it corrupts the very institutions of law and administration upon which civilised societies are structured. Gretley shows this.

How this has played out can be even better understood by looking at OHS prosecutions since Gretley and at the injustices that the prosecutions have imposed on ordinary people in NSW.

18. PROSECUTIONS SINCE GRETLEY

The structure of the NSW OHS laws, corrupted as they are by the presumption of automatic guilt on the part of the employer, has led to disturbing outcomes.

18.1 Coupland Cranes (16)

This was a 2005 prosecution. The case involved a small, two-director company running a crane business. While lifting metal roof sheeting, the crane made contact with power lines resulting in electrocution of a worker on the roof.

The two employees operating the crane were ticketed and experienced. The directors of the company were not present at the time of incident and were not directly involved.

One director of the company was prosecuted.

The Judge questioned why the employees were not prosecuted. The judge said "Being experienced operators they had a clear responsibility to undertake the work safely. They manifestly failed in that regard." (s15)

Yet the employees were not prosecuted because the structure of the OHS Act limits the liability of employees in comparison to the employer.

18.2 Coleman Joinery (17)

This was a 2004 prosecution involving a case of extreme bullying of a 16-year-old. The youth was wrapped in clingwrap by five workers and placed in a wheelbarrow. The workers forced glue, sawdust and water into the youth's mouth.

This was a family company with four directors. Two directors were prosecuted. The company was fined $24,000. The directors now have criminal convictions. Yet the directors did not know of the bastardisation until after the incident, did not condone or allow such behaviour, were not present at the time of the incident, but still they were held responsible.

The employees who conducted the bastardisation were subsequently convicted under NSW OHS laws but received fines of less than $1,000. These low penalties reflect the lesser liability assumed for employees as compared with employers under the NSW OHS Act.

In this case, the persons who personally committed the assault against the 16-year-old received slight penalties yet the employer (the company and directors) who took no personal part in the assault received high penalties. This is blame transference of the worst sort and it occurs by design and intent under the NSW OHS Act. This is wrong. This is dangerous.

Stable and law-abiding societies depend heavily upon faith and trust in the fairness and integrity of the law. Laws that shift blame from perpetrators to innocent persons are laws that quickly destroy community confidence and faith in the laws and in the judiciary which applies the laws.

18.3 Police Force, 2004 (18)

The NSW Police Force was prosecuted for failing to ensure the safety of a sergeant who was deliberately run down while on highway patrol duties.

The sergeant had detected a speeding vehicle and stepped on to the road to signal it to stop, but the driver increased speed and swerved toward him, hitting him and causing serious injuries.

The Police Force was found to have failed to have in place a safe system of work and provide adequate instruction and training. The judge prescribed a view of safe systems of work required as a consequence of the OHS Act, which included installation of barriers and not stepping out on to the road.

Once again, this is a distortion of OHS principles. The policeman was undertaking his duties as he and thousands of other policeman would do every day. A motorist behaved in an unexpected and criminal manner. The criminal behaviour of the motorist triggered a presumption of guilt under the NSW OHS laws merely as a result of the incident occurring.

18.4 Ridge Consolidated, 2002 (19)

An employee was struck and killed by a vehicle which veered across two lanes of traffic on to the wrong side of the road and through the gap in a safety barrier adjacent to where he was working. The driver was under the influence of alcohol. He was subsequently charged and convicted of dangerous driving.

The employer had logically assessed the risk and erected barriers to protect workers; he did not foresee the entry of a drunken driver (travelling in the opposite direction on other side of road) through the barriers placed diagonally to protect against entry of vehicles travelling towards the worker on his side of the road.

However the Court commented: "As has been frequently stated by this Court, the duty of employers under the Occupational Health and Safety Act is absolute. It is not confined to the taking of precautions only when there are warnings or signals of danger or when experience indicates that a risk to safety has arisen and requires a remedy" [Ferguson v Nelmac Pty Limited (1999) 92 IR 188.]

Once again, the criminal and unexpected behaviour of a motorist triggered "employer guilt" under NSW OHS laws, despite the fact that the employer had gone to considerable trouble to anticipate safety risks and acted to prevent safety risks.

18.5 Kirk Group Holdings, 2005 (20)

A farm manager was killed when an ATV (off road vehicle) he was riding overturned. He had driven down a steep hill towing a load attached to the carry racks (both in contravention of the ATV safety manual) rather than driving along the road that had been purpose-built to avoid driving down the slope.

The manager (a personal friend of the owner) had vastly more experience of farm equipment than the owner, a city businessman.

The court accepted that the manager had probably read the ATV safety manual, which specified the maximum gradients on which the ATV could safely be driven and which prohibited towing from the carry racks. The Court also accepted his high level of experience, that he was of independent mind, and acknowledged his recklessness.

Despite this, and the fact that the purpose-built road had been constructed to eliminate the risk, the Court found that the owner had inadequately trained and supervised the manager and also exposed other workers, intermittently on the farm, to risk. Despite the fact that the ATV was only used by the manager, the court found that the owner did not ensure other workers were properly trained in the use of the ATV, did not restrict access to the ATV, did not provide workers with information in the ATV Safety Manual or supervise to ensure that they used it safely.

Once again, this demonstrates the point that the mere incidence of such an event triggers employer guilt. The deceased employee, whose actions apparently caused his own death by disobeying the safety rules he himself managed, was not taken to have any guilt. This is dangerous OHS law.

By comparison, the Victorian OHS laws would have required a court to investigate the behaviour of the employee-manager, the employer and any other party, to look at the facts and to allocate liability proportionate to each party's contribution to the incident.

18.6 Bank Hold-ups and the like

One of the clearest demonstrations of the flawed structure of NSW's OHS laws occurs in relation to armed hold-ups, where criminals enter premises and conduct violent hold-ups.

If the criminals are caught, they are tried in criminal courts where they are accorded the presumption of innocence, guilt must be proven beyond reasonable doubt and they have full legal rights to appeal.

Yet the people subject to the hold-up face a very different situation under NSW OHS laws. The legal employer is held to be guilty simply as the result of a holdup. Managers can be charged under the presumption of guilt features of the Act. Prosecution occurs in the NSW industrial relations courts where appeals are prohibited.

The criminals who commit the hold-ups are given greater access to justice than the victims. This is a distortion of justice of the highest order. And OHS prosecutions under such circumstance have been a regular occurrence since the Gretley case in 1996.

- The ANZ Bank was fined $175,000 for four robberies in an eight-month period during 2002-03 at its Peakhurst branch. The Bank had guards posted as extra precautions, but the Bank had an "absolute duty" under the 2000 OHS Act. (21)

- The ANZ Bank was fined $156,000 in 2003 for a robbery in June 2002 at the Brookvale Branch in NSW. (22)

- The Commonwealth Bank was fined $25,000 under the 1983 OHS Act following a 1999 armed holdup. (23)

- The South Sydney Junior Rugby League was fined $195,000 after a thief took a doorman hostage and robbed the club. (24)

- Franklins supermarket was fined $94,500 after three workers were robbed at gunpoint in Sutherland in 2003. (25)

18.7 Plumber guilty (26)

Perhaps one of the saddest cases of justice gone haywire is the case of a plumber who was prosecuted after a scalding incident.

At a nursing home, an elderly woman was badly scalded while bathing after a temperature control valve in a hot water system failed. The plumber who maintained the valve was found guilty and fined. Yet the evidence showed that the plumber was particularly diligent in his maintenance regime, being fully aware of the risk that attached to failure. The plumber had strictly followed the manufacturer's maintenance guidelines. The scalding occurred because of a malfunction in the internal workings of the valve that could have only been found beforehand by microscopic inspection of the internal parts of the valve.

The fact of the incident occurring resulted in the plumber being found guilty under NSW OHS laws.

19. LET'S DO A DEAL

The injustice associated with NSW OHS prosecutions is systemic. It is ingrained in the structure of the OHS legislation and in the approach to the prosecution processes. The industrial relations jurisdiction is not an appropriate place for such cases to be heard, but this does not mean that the judiciary considering or deciding on cases is behaving inappropriately. The judiciary is instead doing what is required of it by the legislation. It is required to find that no matter how careful or diligent the behaviour of an employer or manager, the fact of an OHS incident occurring requires the finding of guilt. This star chamber-like process is a direct consequence of the design of the OHS legislation.

The outcome is that, in NSW, OHS prosecutions are operating at a 96 per cent conviction success rate. (27) And NSW conducts five times more prosecutions than both Victoria and Queensland. That is, the prosecution rate in NSW is way out of proportion to the rates for the rest of Australia, with conviction in NSW almost being a predetermined outcome. The NSW legal fraternity knows this. Its standard advice to accused clients is to plead guilty and seek a deal with the prosecutor. This "plead guilty" advice has become a major contributor to the massively high conviction rate.

NSW is no longer a State in which OHS prosecution or conviction is based on assessment of the facts of reasonable and practicable behaviour. Instead it is a "let's do a deal" State. It's become an ugly game show in which the negotiation of the fines and/or possible jailing occurs because the accused is confronted by a stacked legal process.

20. MORE ON THE POLITICS OF THESE BAD LAWS

On the surface, these bad NSW OHS laws have for some time attracted the appearance of cross-party political support and even support within some sections of the business community. But by late 2005 this had changed. Why the appearance of support and why the change?

In 2000, the NSW Government introduced new OHS laws which, in effect, picked up and added to the flawed elements of the 1983 OHS Act. There was no discernibly significant agitation against the 2000 OHS Act when it was introduced from either the political or business sectors at the time. But agitation against the NSW OHS laws began to become apparent soon after the 2000 Act was passed. This occurred because, following Gretley, there appeared to be a new-found aggressiveness in the OHS prosecution of employers in NSW. Gretley really was a watershed.

The clearest indication of the new and aggressive OHS prosecution regime is provided by the total of fines imposed.

- In 1998–99, total NSW OHS fines for the year amounted to $2.97 million.

- By 2003-04, the total had risen to $13.3 million for the year.

And in this period, NSW, with only a third of the Australian population, recorded 63 per cent of all OHS prosecutions in Australia, 66 per cent of all OHS convictions and 64 per cent of all fines. (28)

This significantly new aggressive approach to prosecution was arguably the direct result of political campaigning conducted by the NSW union movement following Gretley. The haters of employers were baying for OHS blood. There was a political demand to make examples of employers. It appears that the NSW prosecution process responded. This was facilitated by the fact that unions in NSW had been given the power under OHS laws to act as a prosecutor and were able to have (and did have) their legal costs covered by defendants. Moreover, they could (and did) receive half of the fines. NSW unions make money from NSW OHS prosecutions -- something that still happens in NSW today.

They have been able to achieve this because of a deep, intimate and institutionalised political connection with the NSW ALP Government. Further, they have conducted successful moral intimidation against the NSW business community by accusing any who oppose them of endorsing, or being apologists for, bad work safety practices. Business and business associations have generally been caught off-guard by this intense moralistic public relations campaigning. In response, many organisations fell silent or acquiesced in the belief that, rather than opposing bad laws, they had to minimise the damage.

But what occurred (and continues to occur) is that the consequences of the flawed OHS laws and the failings of the prosecution process began to be felt not only by the business community but, perhaps surprisingly, by the NSW legal community as well.

There is anecdotal evidence that even within the ranks of labour lawyers there is deep concern, even resentment, about NSW's OHS laws. Increasingly, those laws are being seen within significant and influential sectors of the NSW legal fraternity for what they are -- an affront to justice.

Within the NSW business community, the objection to the laws is now up-front and obvious. In 2005, the NSW Government, under campaigning pressure from the union movement, moved to introduce industrial manslaughter laws. An OHS Bill was introduced to enable the jailing of executives and managers following the death or serious injury of a person in a workplace. A storm erupted from the business community -- from the small through to the large business sectors. The Government had to back down on significant aspects of the Bill, but eventually passed the Bill with public support from some business groups and continuing opposition from others.

An important aspect of how the ALP massages NSW politics is that it always seeks to contrive the appearance of some business support for controversial legislation. It achieved this with the Deaths Act of 2005. But this did not hush business opposition. In late 2005, the NSW Government conducted a public review of its OHS laws.

For the first time ever, every single business and industry association submission called for substantial change to the core structures of NSW's OHS laws. They called, in particular, for the elimination of the presumption of guilt and for all parties to be allocated liability according to what they reasonably and practicably controlled. This signalled a collapse in the political settlement that the NSW Government had hitherto managed in relation to its OHS laws.

In May 2006, the NSW Government announced its intention to change the core structure of its OHS laws. (29) But it has received a nasty and bitter reaction from the NSW union movement, which has described the proposed changes as a betrayal of labour principles. The NSW Government now finds itself at political war with its core political constituency and support base -- the union movement. (30)

APPENDIX A

MAPS

THE OFFENDING MAPS

These are the two faulty maps supplied to the Gretley mine by the DMR.

Note: There was never a "bottom seam" working. The mine surveyor in 1892 re-orientated his map of mine workings, overlaying his first attempt, in black, with his corrected version (in red), but failed to note this on the same map. The DMR during the 1960s arbitrarily assigned each set of workings to different levels (460 and 521 feet). After the disaster, the Company drilled probes into the 521 foot depth and found no workings at that depth.

MAP 1

THE OLD WORKINGS (OVERLAID AND NEW DIGGINGS)

These are the two faulty maps supplied to the Gretley mine by the DMR.

This map shows what the 1892 map looked like with the overlay of 2 drawings and the location of the 1990s' workings surrounding the old workings.

MAP 2

THE POINT OF DISASTER

MAP 3

THE INTENDED PROBES

Just days after the disaster happened, the digging was to stop to send out "probes". These probes would have discovered the presence of the old water-filled mine.

APPENDIX B

CFMEU PASSION

B1. "... the Unions efforts to support prosecutions"

"The Gretley prosecutions and convictions is one of the most significant developments in the history of our industry." [Common Cause, Oct/Nov 2004]

B2. Extracts from www.cfmeu.com.au April 2005

Mining companies should not be allowed to get away with murder in NSW

While booming coal prices and record productivity have sparked billion dollar profits for the companies that dominate Australia's mining industry, NSW coal mineworkers are still entrenched in a bitter fight for greater safety conditions and standards.

Our Union's safety campaign has brought us to the brink of industrial action several times recently as mining companies continue to insist that they be exempt from being held accountable for criminal and negligent actions that lead to deaths and injuries in the State's coal mines.

At present, one of the world's most powerful and richest coal companies, Xstrata, is engaged in a NSW Supreme Court challenge to the State's health and safety laws following successful prosecutions that led to the NSW Industrial Commission imposing a record $1.47M fine on Xstrata over the deaths of four coal miners at the company's Gretley Colliery in 1996.

... Xstrata is supported in its challenge by the other powerful coal mining companies through the NSW Minerals Council. These include BHP Billiton, which has just declared a record $8.3 billion profit, and Rio Tinto, which is on track for a record $5 billion-plus profit.

These powerful companies are attempting to exonerate employers who kill people at work. They are seeking to exempt themselves from laws that apply to everyone else in the community. They are seeking to restore the historical status quo in which mining companies in Australia have literally gotten away with murder.

It has taken 200 years and the deaths of an estimated 3,000 NSW coal miners before a mining company has been successfully prosecuted for OHS breaches in NSW.

And they don't like it.

For them, and us, the successful Gretley prosecutions are a watershed. The mining companies now fear that they will be held accountable for OHS breaches that leads to the loss of miners lives.

... In deciding to challenge the laws in March this year, Xstrata and the mining companies that support it are drawing their line in the sand. Almost nine years after the Gretley disaster, mining companies are still demanding immunity from proper legal enforcement of the State's health and safety laws.

... Coal mining is internationally recognised as the most hazardous industry in the world. The workers in it need all the protection they can get. The workers are entitled to expect nothing less from a Labor Government nor will our Union settle for anything less.

B3. "The Miners Union today warned of a significant industrial backlash in the nation's coal mining industry as two of the biggest coal producers in Australia attempt to overturn criminal prosecutions in occupational health and safety laws." [www.cfmeu.com.au 31 Jan 2005]

B4. CFMEU pressured the Government to undertake the prosecutions. [The 7-30 Report. Interview with CFMEU. 2003. Ref s997152]

B5. The CFMEU "... said representatives from every pit in NSW would rally in Sydney on Monday at 9-30am outside the Court of Appeal in Queens Square to protest against Xstrata's appeal." [Sydney Morning Herald, March 12 2005]

APPENDIX C

EVIDENCE THAT SEVERAL OF THE DECEASED GRETLEY MINERS WERE EMPLOYED BY UMSS

"Report of a Formal Investigation under Section 98 of the CMRA 1982" by his Honour acting Judge JH Staunton, p84:

"The company known as United Mining Support Services Pty Ltd was also given leave to appear. United Mining Support Services Pty Ltd is a company part owned by the CFMEU. Three of the four men who died ... were contractors supplied by the United Mining Support Services Pty Ltd. ... Although given leave, it chose not to appear." (P84)

ibid., p86:

- John Michael Hunter (Deceased) (Employed by UMSS)

- Damon Murray (Deceased) (Employed by UMSS)

UMSS employment records show

- Damon Murray (deceased) (96.01)

- John Hunter (deceased) (96.02)

- Mark Kaiser (deceased) (96.03)

(brackets show Gretley Inquiry Exhibit Number)

APPENDIX D

EVIDENCE THAT CFMEU HAD OWNERSHIP OF UMSS

D1 CFMEU Statement February 1997: "The CFMEU is involved with United Mining Support Services in the NSW Hunter Valley." [CFMEU policy paper/backgrounder by Gary Wood, CFMEU WA District Secretary and Tony Maher CFMEU Senior General Vice President. "Contracting out in the Mining Industry", Feb "97.]

D2 "The CFMEU believe there is a lack of regulatory protection for the growing number of contract workers within the industry" "The CFMEU is hesitant to condemn contractors because it owns half of United Mining Support Services, one of the oldest contract employers." [University of Technology Sydney. "Mining Australia", 2004]

D3 Peter Murray, General Secretary Northern Division CFMEU October 2005: "As General Secretary of our great Union (CFMEU) ..." "I held the position of Chairman of the recently disposed Union-majority-owned United Mining Support Services. I am currently Chairman of the United Colliery Joint Venture mine in the Hunter Valley."[Peter Murray. General Secretary CFMEU. Piece in "Common Cause", Oct-Nov 2005.]

D4 "Peter (Murray) held the position of Chairman of United Mining Services for some 7 years and a director for 5 years prior, until the sale of the company in December 2004". "Peter Murray was appointed General Secretary of the CFMEU Mining & Energy Division in August 2005. Prior to that Peter was the District President of the Northern District since August 2003, following the position of Vice President since 1990." (ie) Peter Murray was on the Board of UMSS from about 1992. [About us-Board Members. Coal Services Pty Limited. www.coalservices.com.au Coal Services was formed in Jan 2002 from the merged activities of the Joint Coal Board and Mines Rescue Board. It is responsible for workers' compensation, OHS and mines rescue to the NSW Coal Industry.]

D5 "... using the United Mining Support Services (UMSS) for supplemental labour (sub 48). UMSS is part-owned by the mine workers union." [Productivity Commission report into the Australian Black Coal Industry. July 1998, page 103]

D6 Committee of Management of National Office of CFMEU [CFMEU National Office Financial Report year ending Dec 2005]

Trevor Smith, Tony Maher, John Maitland, John Sutton, Bruce Watson, Peter Murray, George Coates, Michael O'Conner, Leo Skourdoumbis, Albert Littler, Time Woods, Dave Noonan, Lindsay Fraser, Chris Price

APPENDIX E

D1. The Victorian OHS Act 2004 (Most States are close to this model)

These are the clauses from the Act describing the duties each person has. Note the reliance on ensuring safety given what is "reasonable and practicable". This complies with international obligations as determined by an ILO Convention to which Australia is a signatory.

General

20(1) To avoid doubt, a duty is imposed on a person by this Part of the regulations to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, health and safety requires a person ...Employers

21(1) An employer must, so far as is reasonably practicable, provide and maintain for employees or the employer a working environment that is safe and without risks to health

21(3)(a) a reference to an employee includes a reference to an independent contractor. ...

23(1) An employer must ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, that persons other than employees of the employer are not exposed to risks. ...

Self-employed

24(1) A self employed person must ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, that persons are not exposed to risks. ...Employees

25(1) While at work an employee must

- take reasonable care for his or her own health and safety; and

- take reasonable care for the health and safety of persons who may be affected by the employees' acts or omissions. ...

Managers or controllers of worksites

26(1) A person who (whether as an owner or otherwise) has, to any extent, the management or control of a workplace must ensure so far as is reasonably practicable. ...Designers of plants

27(1) A person who designs plant who knows, or ought reasonably to know, that the plant is to be used at a workplace must

- ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, that it is designed to be safe. ...