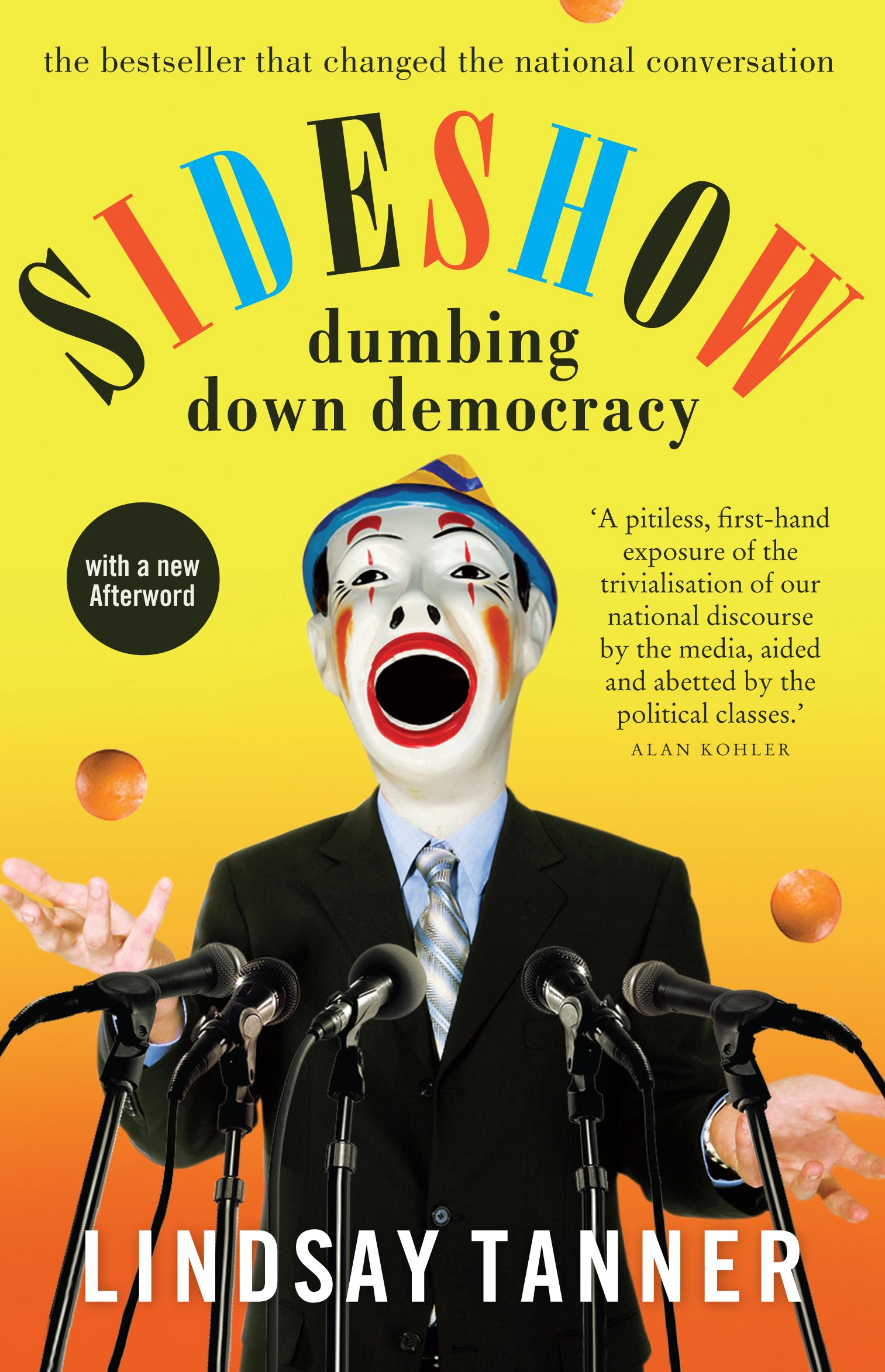

Sideshow: Dumbing Down Democracy

By Lindsay Tanner

(Penguin, 2011, 240 pages)

Late last year the English journalist and cricket writer Matthew Engel spent some time in Australia. He found much to admire. Aside from the extraordinary success of our economy ''the most successful ... of any western democracy'', he was impressed by our ''remarkable respect for the rule of law and a great sense of civic responsibility.''

Late last year the English journalist and cricket writer Matthew Engel spent some time in Australia. He found much to admire. Aside from the extraordinary success of our economy ''the most successful ... of any western democracy'', he was impressed by our ''remarkable respect for the rule of law and a great sense of civic responsibility.''

And then he visited Canberra. ''I have seen a few crazy parliaments'', he wrote in the Financial Times:

I have watched the Israeli Knesset, where one extreme would happily exterminate the other -- and the Dáil in Dublin, the only known gathering of inarticulate Irishmen. I have seen the empty shell that constitutes the US Senate. I have done time at the Commons, and been appalled by the pathetic lack of individuality of the whipped curs. I thought I was unshockable. But Canberra's House of Representatives is the worst. These curs only snarl as instructed.

The empty robotic nastiness of public life in Australia has been with us so long that we fail to notice how unusual it is.

It is only when you have lived overseas that you realise that it is only in Australia that politicians cannot open their mouths except to insult each other.

Lindsay Tanner is a clever and thoughtful man, who having ''devoted his life to the serious craft of polities'', admits he found the previous election dispiriting. He is distressed by what politics has become in this country. He can see -- as anyone can -- that by behaving as mindless automatons, endlessly repeating stupid slogans, politicians drive us to change the channel whenever their heads appear on our screens.

You might have thought therefore that -- free-at-last -- the former finance minister might have used his first book after leaving politics, Sideshow, to chastise his former colleagues for their behaviour.

Not a bit of it. Apparently the debauched state of public life in Australia is not the fault of its participants. It's all the fault of the media. Yes, Tanner admits, we politicians ''indulge in puerile stunts in parliament designed to win momentary television coverage'', yes we gate-crash light entertainment programs. Of course we run scare campaigns about higher taxes, boat people, or people's working conditions. But it's not our fault. Says Tanner:

No one in the Labor Government, or indeed the Howard Government, should be blamed for surrendering to these pressures. If we had taken a purist approach, we would have left ourselves naked in the middle of the media storm, defenceless against the irresistible commercial pressures to sell newspapers and win ratings.

What utter self-serving nonsense! Politicians behave as they do because it suits their purpose to do so. This is demonstrated by the ease with which they switch off the abuse when it suits them. When one of them rides on ahead and it comes time in parliament to praise their fallen colleague, they gush about the public spiritedness and noble achievements of men and women they never had a good word for when they were alive.

If journalists wait for any scrap of unscripted behaviour -- whether it's tiny differences of opinion between politicians from the same team, or unintentionally revealing body language -- to pounce on to blow it up and distort it into a row or a gaffe, whose fault is that?

I would argue it's theirs, not ours, because of their refusal to drift off message. Even on the ABC's panel show Q&A, which is meant to allow a flow of ideas, politicians never drift from their script and say anything interesting, (in marked contrast to its British equivalent Question Time).

Which is not to deny that of course a lot of what passes for political journalism in this country is not much chop.

Yes, we distort things to create conflict where perhaps none exists, and of course we sensationalise things to attract our audience's attention.

But we are competing for the attention of an audience that welcomes politics as child welcomes a dose of Agarol.

To be fair to Tanner, he does not accuse the Australian media of behaving as it does out of caprice. He acknowledges most Australians don't want to hear about serious politics. He blames this indifference in part on prosperity. It was different, he suggests, back in the 1980s when there was a widespread agreement that Australia needed to do something to save its economy. The apathy of the public -- and hence the media -- can be explained, in part, by the fact we have not had a recession for the past twenty years.

There is no doubt something to be said for this argument, reminiscent as it is of Malcolm Fraser's promise that he would run the country so well that he would get politics off the front page of the newspaper.

On the other hand, the United Kingdom and United States have both suffered vicious recessions in the past three years without any apparent flight to quality in their media -- indeed, in America the ''serious'' newspapers that Tanner seems to favour are losing staff and market-share at such a pace that their futures have been called into question.

Alongside prosperity, Tanner blames the proliferation of media for the public's escapism. At times he seems to come close to despairing of the way the variety of modern media make it easy for the average punter to tune him and his colleagues out.

But while he may pine for the golden age of the mass media, with middle-brow mass audiences forced to absorb information thrown at them for want of choice, he knows it isn't coming back.

Tanner believes the consequences of this decline imperil democracy:

There is a clear risk that genuine political engagement with the political process will shrink back into the provenance of an educated, aware minority as the media connection between ordinary citizens and the decision-making process continues to wither.

We could he warns, ''revert to the kind of restricted democracy that prevailed in Europe in the nineteenth century, with education and engagement the barriers to involvement, instead of property and income''.

There is no doubt the problem is a real one, though the ignorance of the masses has been one of the arguments against democracy since time immemorial. What we ought perhaps to ask ourselves, is how is it that relentless dumbing-down of mass culture has taken place at a time when western societies have allegedly never been better educated?

That there are no real answers to the problem is demonstrated by how pathetic and small are the glimmers of hope he offers for those worried about the state of political culture.

Bloggers -- yawn -- feature high on the list, suggesting as they do, that ''the internet is broadening quality commentary on issues and ideas''. He then reels off a list of bloggers, ignoring the fact that the best-read political blog in Australia is written by Andrew Bolt, a journalist who works for the very oldest of medias, the newspaper.

Other suggestions are bizarre, including his idea that American crime series Law and Order is a possible template for communicating complex policy issues to Australian audiences.

(Actually perhaps this isn't such a bad idea -- if they ever make a drama about Rudd's office they could do worse than call it The Special Victims Unit.)

Oddly, the most vicious, ill-informed and partisan of the old media -- talkback radio -- is exempted from Tanner's criticism. Shock jocks, are, he explains ''a vital point of connection between the democratic process and the wider world''. And while Tanner was apparently ''occasionally hammered a little unfairly'' when he appeared on them, ''they invariably allowed me to get a serious point across.''

Tanner ends his book with a call to arms which is really a howl of despair:

We have no magic wand to solve the sideshow problem, but by acting individually and collectively we can start to push back against the forces of entertainment colonising our democracy.

Earlier, in a passage of his book devoted to ''gotcha'' journalism, Tanner recounts an anecdote from an interview he once gave to Leigh Sales. Asked to sum up Kevin Rudd in one word, he answers ''nasty''. Alas he had misheard the question; he thought he was being asked to sum up, John Howard. Luckily the kind people at Lateline edited it out.

Tanner does not reflect what it says about him, or the political culture he comes from, that such a childish insult was the first word that popped into his head.

If he wants to start pushing back against the entertainment values he despises, and to get the people Australia engaging with serious ideas he professes to love, he would have done better to have called on his former colleagues to stop acting like moronic thugs.

The fault, dear Lindsay, lies not in the stars of Sunrise but in yourselves.

No comments:

Post a Comment