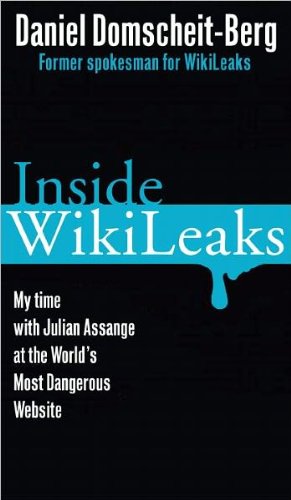

Inside Wikileaks: My Time with Julian Assange at the World's Most Dangerous Website

By Daniel Domscheit-Berg

(Jonathan Cape, 2011, 304 pages)

There aren't many people ambivalent about Wikileaks. US politicians have called for the site to be shut down. Politicians and commentators have called for its founder, Julian Assange, to be assassinated. Wikileaks and Assange are also the darlings of the left as they; somewhat ironically, progressively expose the absurdities and misbehaviour of big government and occasionally big business.

There aren't many people ambivalent about Wikileaks. US politicians have called for the site to be shut down. Politicians and commentators have called for its founder, Julian Assange, to be assassinated. Wikileaks and Assange are also the darlings of the left as they; somewhat ironically, progressively expose the absurdities and misbehaviour of big government and occasionally big business.

I suspect for most people, their reaction is a mixture of interest and caution about the benefits of having various governments' dirty linen aired, especially since they mostly tell us what we already knew. And while Assange has a roguish charm while questioning Prime Ministers on live television about whether they're guilty of treason, at a certain point the justification for his moral piety peters out.

Which is why Daniel Domschiet-Berg's Inside Wikileaks: My Time with Julian Assange at the World's Most Dangerous Website is a worthwhile read for Wikileak lovers and haters alike.

In short, Domscheit-Berg was second in charge to Assange, with whom he had a chaotic relationship that progressively declined as the site attracted international fame and attention.

Whether or not Domscheit-Berg's motivation for writing his tale about his experiences with Assange is to inform how he ''experience[d] firsthand how power and secrecy corrupt people'', jealously, or simply to take the gloss off Assange's reputation, the book makes you sympathetic to his situation.

He writes that ''Julian Assange ... was my best friend ... the site made him into a pop star, one of the most intriguingly zany media figures in the world'', but then details how anyone who helped him reach this status was simply someone to be used and abused.

The two originally shared a kinship built around the common idealistic purpose of their project, in a world where they dreamed ''there would be no more bosses or hierarchies, and no one could achieve power by withholding from the others the knowledge needed to act as an equal player.''

But like all grand projects led by partners, friction quickly rose as Assange sponged off Domscheit-Berg, abused the friendship with a callous indifference and then struggled with the moral dilemmas resulting from their exploits.

What became apparent is that while Assange dreamed of being the architect of an intellectually inconsistent, anarchic, pseudo-communist, property and privacy-free world built around his interpretation of equality, he also had delusions that he'd somehow sit atop. It is very Road to Serfdom.

Domscheit-Berg argued his objective was ''to shake up society ... to knock the bastards on the head, as he once put it''. Though who ''the bastards'' are is amorphous depending on who is in a position of power and authority at any given time.

One of Assange's favourite sayings was ''the man in the uniform has to learn his lesson''. It was a concept that clearly drove him in all his dealings with authority. Domscheit-Berg writes about Assange's feisty attitude with a story of him refusing to pay a questionable fee to a train ticket inspector.

Considering the circumstances now facing key leaker and ''man in the uniform'' Private Bradley Manning, who allegedly supplied Wikileaks with its famous US State Department documents; it shows he applies the principle universally.

And based on his experience with Assange, Domscheit-Berg clearly started to doubt aspects of the vision and also the benefits of Assange's status in their new world order.

It wasn't as though Assange's friction was isolated to Domscheit-Berg. The stories he cites of his history with Assange mostly involve a constant state of conflict from the time they attended a German conference, where they ''[encountered a lot of resistance from data-protection activists. 'Protect Private Data -- Use Public Data' -- that was the slogan''. Domscheit-Berg confessed that they ''operated in a gray area'', because as demonstrated by the release of bank account details for suspected tax evaders earlier this year, they had little interest in personal privacy.

But while Assange is painted as the comparative villain, Domscheit-Berg clearly wasn't a defender of the private domain.

In response to publishing leaked emails from Sarah Palin's hacked personal account, Domschiet-Berg pondered ''what is public and what is private?'', before he and Assange ''were convinced that [they] were strengthening the project by pushing the limits of what was acceptable.''

And the lack of interest in the legitimacy of the private domain clearly drove much of Wikileaks' progress.

One of their early leaks was that of a donor list for US Senator for Minnesota, Norm Coleman, caused by a ''misconfiguration'' on his website resulting in the leak of ''not only the names of Coleman's campaign supporters but their exact credit card details, including security codes, as well.''

Assange's lack of respect for private property was even on display with his personal behaviour as he regularly stole or destroyed other's property for his benefit. Domscheit-Berg relays one story, where in a private computer server storage facility, Assange ''grab[bed] a power cord from the room next door and cut it in two ... after a bit of tinkering he has a new power source for his laptop.''

To be fair, Assange also applied this lack of respect for the private domain to himself. When faced with the unintended CC'ing of an email to their donors, Wikileak's own donor list was promptly leaked to their own website. After some moral introspection, he conceded it had to be published like any other leaked document. Yet Wikileaks also forces its employees to sign a draconian confidentiality agreement which forbids them from leaking.

But the absence of a private domain is not Assange's only disconnect from the realm of reality.

He clearly got swept away with his own imagination and self-importance. Perhaps when Wikileaks was emerging, governments may have been spying on his conduct, but without evidence he also indulged in the fantasy of being a wanted man. He clearly enjoyed it, according to Domscheit-Berg, Assange was ''perpetually concerned with finding a new look and the perfect disguise.''

And his own position within Wikileaks was also central to maintaining his deluded world.

Domscheit-Berg pondered whether Wikileaks itself had developed into some kind of religious cult.

It's become a system that admits little internal criticism. Anything that went wrong had to be the fault of someone outside. The guru was beyond question. The danger had to be external.

At one point after receiving a leak about Scientology, Domscheit-Berg argues becoming an ''all-consuming religion would have simplified a lot of things'' for Wikileaks.

For Assange, personal responsibility was clearly alien, with Domscheit-Berg claiming ''rarely was anything [Assange's] fault ... instead he blamed banks, airport staff, urban planners, and, failing that, the [US] State Department''.

By the time the reader reaches the final chapters, Assange symbolises a sort of selfish pseudo-celebrity effigy, with a casual indifference to his claimed cause, those it adversely affected and even those who supported him.

Meanwhile Domscheit-Berg portrays himself as a reasonably honest broker who never really strayed from Wikileaks original intentions. But behind his progressively dying support for Assange, he comes across as someone suffering from Stockholm syndrome to an intellectual and philosophical captor who he sympathises with and loves.

While the world waits to see whether Assange will be extradited to Sweden and allegations against him are pursued there, and elsewhere, there is merit to reading Domscheit-Bcrg's book to give an idea of how he ended up in this situation.

This reader started with a mixed view of Asssange, but by the last page there is scant reason to feel sorry for his predicament; because it might be the first time in life he's had to face responsibility.

For Assange, such a conclusion should be troubling, because his brand is intrinsically linked to Wikileaks and vice versa. This book gifts Wikileaks the weight of Assange's shortcomings and ego, and diminishes the altruism that may have existed behind its foundation.

No comments:

Post a Comment