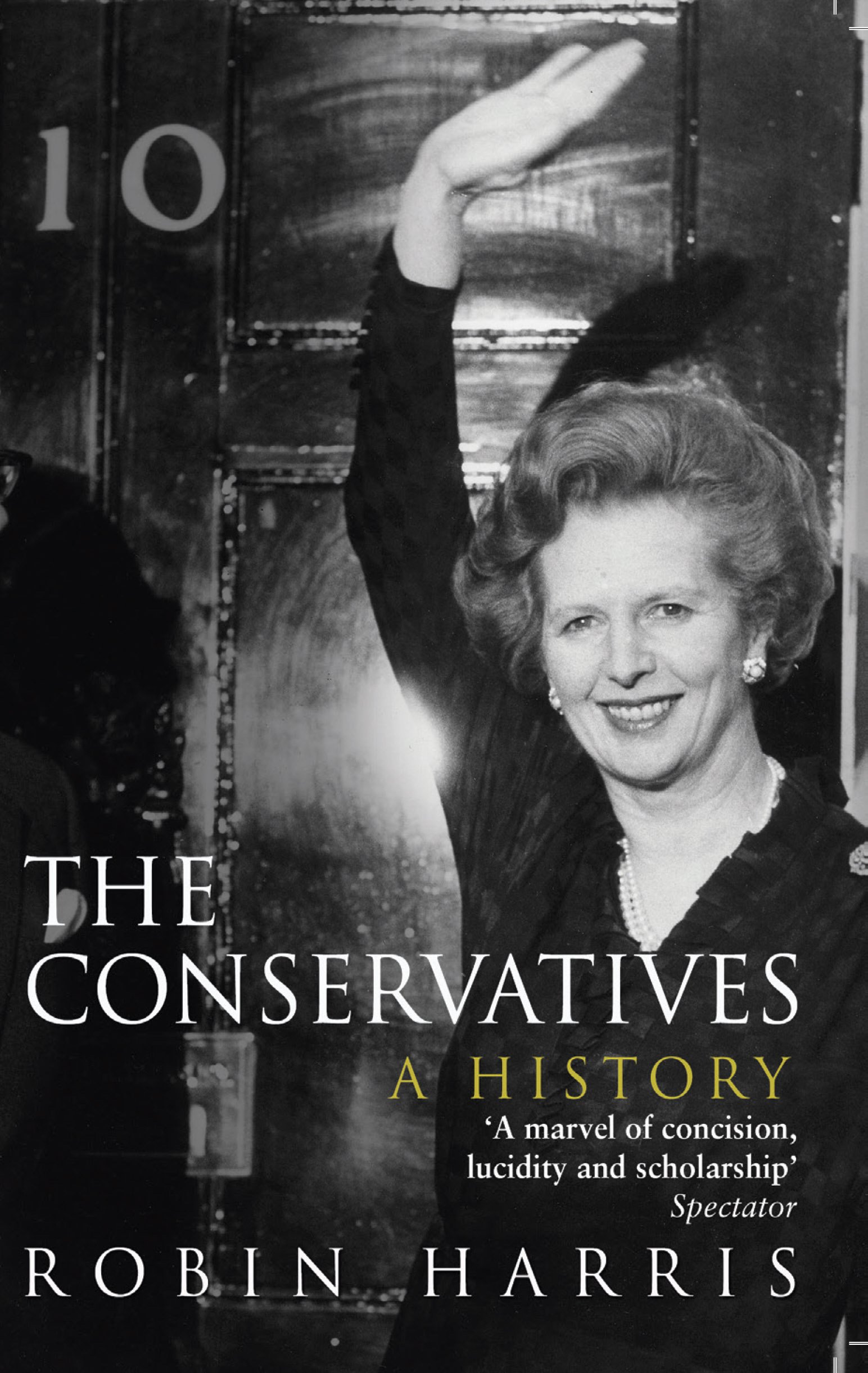

The Conservatives: A History

by Robyn Harris

Bantam Press, 2011, 640 pages

This is a marvellous book. It has many things to recommend it. A list of the book's many merits would go something like this (in order of importance): it's interesting; it's opinionated; it's extremely readable; it explains why John Major and Edward Heath were failures; it predicts David Cameron will be a failure; and it nominates only Lord Salisbury, Benjamin Disraeli, Bonar Law, and Margaret Thatcher as Conservative leaders who can in any way be regarded as good leaders of their Party. (That Churchill qualified for greatness is not disputed. But Churchill was leader of the Conservatives in name only. He did nothing to advance the interests of the Conservative Party, hence the result of the 1945 general election.)

This is a marvellous book. It has many things to recommend it. A list of the book's many merits would go something like this (in order of importance): it's interesting; it's opinionated; it's extremely readable; it explains why John Major and Edward Heath were failures; it predicts David Cameron will be a failure; and it nominates only Lord Salisbury, Benjamin Disraeli, Bonar Law, and Margaret Thatcher as Conservative leaders who can in any way be regarded as good leaders of their Party. (That Churchill qualified for greatness is not disputed. But Churchill was leader of the Conservatives in name only. He did nothing to advance the interests of the Conservative Party, hence the result of the 1945 general election.)

The Conservatives: A History is about people first and policy second. That's not an accident. In fact it's the demonstration of the thesis of the book. Because the Conservative Party encompasses an array of ideologies and philosophies that is almost alarming in its range, any leader of the Conservatives therefore has enormous scope to impose their own vision on the party. The Conservative Party is hostage to its leader. In that regard it's very similar to the Liberal Party in Australia.

Harris cites Michael Oakeshott for the statement that conservatism is not a political program. "The link between the conservative mind and Conservative politics is indirect, and it stems from the conservative person's attitude to change ― namely that he or she is suspicious of it". As Oakeshott famously said, conservatism is a "disposition". Harris begins the story of the Conservatives with Edmund Burke and the Tories and the Whigs, but it's with Robert Peel that the modern-day party starts to take shape. Harris is sympathetic to Peel's effort towards Catholic emancipation, but can't forgive Peel for causing the Tories to split over the issue. Tory and then Conservative splits are a constant theme of the book. Indeed it's when he writes about the numerous splits on the conservative side of politics, for example, Catholic emancipation, the Corn Laws, parliamentary reform, appeasement, Suez and Europe, that Harris is at his best.

Conservatism gives leaders of the Conservative Party a suite of policy options to choose from. As Harris is not afraid of saying, the Conservatives of the modern era have been happy to hold nearly any ideological position so long as it wasn't outright socialist. While the Conservative Party of course never advocated socialism, in government it usually did nothing to reverse the economic decisions of the Labour Party. So for example Atlee's program of nationalisation in the 1940s was not reversed until the 1980s under Thatcher. And of course no Conservative leader has been brave enough to touch the National Health Service. This is partly because any attempt to undo the NHS is perceived as political doom, and partly it is because the Conservatives are not uncomfortable with a nationalised health system. From the end of the Second World War to Thatcher, the Conservatives were signed-up Keynesians. In fact they were probably more Keynesian than the Labour Party because up until the mid-1960s, the Labour Party was more socialist than Keynesian. Prime Minister Harold Macmillan received economic advice from his friend, the "hyper-Keynesian" (Harris' terminology) Roy Harrod, who was Keynes' biographer. As prime minister, Edward Heath embraced government control over wages and prices.

The Conservatives' approach to political philosophy gives their leaders a great deal of power: leaders make the policy. The consequence of this, as Harris makes clear, is that to change policy, the party must change leaders. As Bonar Law said in 1922, in the context of the debate about whether the Conservatives should remain in coalition with Lloyd George's Liberals, "The Party elects a Leader, and that Leader chooses the policy, and if the Party does not like it, they have to get another Leader".

That sounds not all that different from what happens in the Liberal Party in Australia. The policy of the federal Liberal Party on first the emissions trading scheme and then the carbon tax was never formally voted on by MPs. The only way rank-and-file MPs got to have a say was through their vote for leader. The way the Liberals changed their policy on the emissions trading scheme was by removing Malcolm Turnbull, their leader who supported the scheme. The authority the Liberal Party in Australia gives to its leader was first noted by David Kemp writing about Malcolm Fraser. What Kemp said about the Liberals also applies to the Conservatives.

It's because of the power Conservative leaders have that Harris is so concerned about David Cameron. Harris' disdain drips from the page. Under Cameron "Green issues took centre stage. A tree replaced the torch of freedom as party symbol ... The Tory image was too negative, too pessimistic, too unappreciative of modernity, too hostile to diversity. David Cameron cultivated his own image as the opposite. 'Let sunshine win the day!' he exhorted the party conference ― and, whatever that meant, his audience seemed happy to go along".

It's because of the power Conservative leaders have that Harris is so concerned about David Cameron. Harris' disdain drips from the page. Under Cameron "Green issues took centre stage. A tree replaced the torch of freedom as party symbol ... The Tory image was too negative, too pessimistic, too unappreciative of modernity, too hostile to diversity. David Cameron cultivated his own image as the opposite. 'Let sunshine win the day!' he exhorted the party conference ― and, whatever that meant, his audience seemed happy to go along".

The philosophical ambiguity of the Conservatives translates into ambivalence about the Conservative Party itself, at least as compared to the Labour Party. Harris captures the difference effectively when he quotes a June 2009 letter from James Purnell to Gordon Brown. Purnell was the UK Work and Pensions Secretary and he had written a letter of resignation to then PM, Gordon Brown.

"In order to assert his nobility of intention, not least in the eyes of Labour Party supporters, Mr Purnell ― with what degree of sincerity it is difficult to gauge ― echoed a sentiment often heard on the left:

'Dear Gordon

We both love the Labour Party. I have worked for it for twenty years and you far longer. We know we owe it everything and it owes us nothing ...'

No Conservative politician at any stage in the party's history would have written such a letter. No one has ever pretended to "love" the Conservative Party ... Any serious Tory figure adopting such a pose would incur immediate ridicule. The Conservative Party exists, has always existed and can only exist to acquire and exercise power, albeit on a particular set of terms. It does not exist to be loved, hated or even respected. It is no better or worse than the people who combine to make it up. It is an institution with a purpose, not an organism with a soul."

That indeed sums up one of the key differences between the Conservatives and their opponents. For Conservatives (and Liberals) an organisation is the sum of its constituent parts. Which is what Thatcher was expressing when she said "there's no such thing as society". Of course she went on to say ― "there are individual men and women, and there are families". The left on the other hand are quite happy to impute a soul into the collective.

Harris is an unabashed supporter of free market liberalism, and he's written a biography of Thatcher which will be published after her death. It's a relief The Conservatives is as a good as it is. Expectations of Harris were high and he's exceeded them.

No comments:

Post a Comment